North Wingfield Road social housing complex.

Created on 25-11-2022

a) Design philosophy

According to the Housing Design Awards, the design of the North Wingfield project took a contemporary design approach, combining the features of local vernacular architecture - as adopted from local farms - with the developer's vision and requirements for flexible, sustainable and innovative housing (HDA, 2021). The architectural office DK -Architects explains that this fusion is represented by massing the morphology of the project, traditional architectural elements (e.g. Dreadnought brick (roof), Janinhoff brick (walls)) with modern elements such as large glazing and aluminium cladding. This combination of materials not only provides an aesthetically pleasing appearance, but also helps to capture heat, ultimately reducing heating energy consumption for at least seven months of the year (DK-A, 2021). In addition, several innovative features have been adapted, including the well-planned use of space and the clear conceptual plans that extends beyond the interior spaces to the shared courtyard, which serves as a social gathering place for the tenants.

The inspiration for the courtyard was derived from the local identity, the farmstead and the crew yard (HDA, 2021). At the same time, the use of a see-through fence, which extends the sightline into the rural surroundings, provides a calming splash of green colour in each residential unit. The semi-raised upper massing extends the courtyard and provides a semi-enclosed space that enhances the feeling of safety and security (DK-A, 2021). Meanwhile, the buildings in the front row clearly stand out from the surrounding buildings through the use of colours and materials and also serve as an entrance gate to the project (DK-A, 2021; HDA, 2021). Each dwelling has its own mini agricultural space, which has proven valuable for the well-being of the residents.

b) Construction process

The skeleton of the building utilises an off-site timber frame method of construction, adopting a semi-modular design principle (Davies & Jokiniemi, 2008). This construction method provides a structure with a superior thermal envelope that requires minimal maintenance and is a 'fit-and-forget' solution for the lifetime of the building. In addition, both labour and material costs were significantly reduced due to less reliance on craftsmanship and multiple suppliers. This is in line with the UK government plans to revamp construction regulations to encourage bold, creative and sustainable construction methods (Davies & Jokiniemi, 2008; Sterjova, 2017).

The construction process started with ground treatment, followed by the casting of the foundations on site. Meanwhile, the timber frames were manufactured off-site at the supplier's factory, which helped to reduce construction work and thus carbon emissions. The frames were then transported to the site for fixing and external treatment, and all the construction work ran in parallel (Wheatley, 2020). The overall process can be seen in Figure 1.

c) Sustainability integration

At the sustainability level, the project worked on several areas to maximise the adaptation of sustainability features and minimise the impact on the natural environment (HDA, 2021).

Creating sustainable buildings

Through sustainable design and layout (e.g. orientation, maximising daylight, optimising solar gain).

Creating high quality outdoor environments (e.g. public and private open spaces that provide shade and shelter and consider flood retention and multi-functional green spaces to protect wildlife).

Use of sustainable water management techniques (e.g. use of sustainable drainage systems and consideration of surface water run-off).

Use of sustainable waste management facilities for private and communal use (through the appropriate provision of waste and recycling bins).

Focus on reducing the use of non-renewable energy.

Reduction of carbon emissions

The project has been designed in accordance with the highest level of building regulations and sustainability standards, in line with the Government's 10-year timetable for all new homes to be carbon neutral by 2016.

Water recycling techniques (such as grey water and rainwater harvesting).

Sustainable Transport (reducing reliance on the private car, incorporating practical and accessible sustainable transport patterns).

d) Energy performance

One of the tools to assess building energy efficiency in the UK is the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), which is defined by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities as:

A rating scheme that summarises the energy efficiency of buildings; it includes a certificate that gives a property an energy efficiency rating from A (most efficient) to G (least efficient) and is valid for 10 years (DLUHC, 2014).

The EPC is produced using the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP), which is defined by the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy as follows:

The method used to assess and compare the energy and environmental performance of properties in the UK [...] it uses detailed information about the property's construction to calculate energy performance (DBEIS, 2013).

The North Wingfield project has successfully achieved a (B) rating - equivalent to 84 out of a maximum possible 100 points with a high potential for an (A) rating equivalent to 95 points (DLUHC, 2021). This score is the result of

The use of high-performance materials with very good thermal transmittance properties (walls: 0.20 W/m²K, roof: 0.11 W/m²K, floor: 0.09 W/m²K).

Well-designed ventilation system that achieves a good air tightness indicator (air permeability 4.9 m³/h.m²).

Low consumption of primary energy of 94 kWh/m2.

Another indicator is the Environmental Impact Score (EIS), which shows the impact of a building on the environment through the estimated carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions calculated at the time of the EPC assessment (DLUHC, 2014). The higher the score, the lower the building's impact on the environment: like EPC labels, the environmental impact score is graded from A to G (DBEIS, 2014). The project generates 1.4 tonnes of CO2 annually. This is less than a quarter of the 6 tonnes emitted by an average household. By improving the EIS rating to A, CO2 production will be reduced to 0.3 tonnes, which will distinguish the project as one of the most environmentally friendly projects (DLUHC, 2021). Figure 2 shows the EPC and EIS breakdowns of the properties.

M.Alsaeed. ESR5

Read more

->

LILAC_Low Impact Living Affordable Community_Leeds

Created on 15-11-2024

Innovative aspects of the housing design/building

The model for LILAC is based on the Danish co-housing model: mixing private space with shared spaces to encourage social interaction. A plethora of green spaces include allotments, pond, a shared garden and a children’s play area. Akin to the private self-contained homes, the ‘common house’ includes a communal workshop, office, post room, food cooperative, kitchen, dining space, social space, bike storage, play area, guest rooms and laundry room. The LILAC community benefit from a large number of communal facilities including: a common house with shared laundry, kitchen, reading area and community area; car sharing; pooling household equipment and power tools; sharing common meals twice per week; growing food in the allotment; and looking for provisions in the local area (LILAC Coop, 2022b; ModCell, n.d.). A shared lifestyle whereby resources and amenities are combined, reduces energy use and saves money.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

Constructed under a Design and Build contract (Chatterton, 2015), LILAC boasts an innovative prefabricated ModCell construction that includes a low carbon timber frame insulated with straw-bale. Residents assisted with the labour, collectively adding the straw bale insulation. External walls and interior finishes are in a lime render, increasing benefits from passive solar heating through thermal mass. Air tightness was prioritised during construction, and triple-glazed windows help to decrease heat loss during winter, allowing for Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery Systems (MVHR) to regulate indoor air temperature. Further energy performance characteristics include solar thermal energy collection for space and hot water heating, 1.25kw solar PV array, with an extra 4kw on the common house (LILAC Coop, 2022b).

LILAC features a flood prevention system whereby a sustainable urban drainage system (SUDS) feeds the central pond. Roof rainwater runoff is collected into water butts that are later used to water the gardens. Overflow from water butts enters the central pond, which discharges into the public drainage system at a reduced rate. Furthermore, all ground surfaces of the site are permeable. Biodiversity planting and a permaculture design certificate course were integrated into the design at planning stage.

Major additional spending decisions were made whenever residents believed it would meet their core values and result in long term financial savings (Chatterton, 2015, p.68). Construction costs were therefore higher than the UK average – a 48 sqm one-bedroom flat cost £84,000 to build at a cost of £1,744 per sqm while the average costs in England were £1,200 per sqm. However, the annual heating demand of the homes is far less than the UK average of 140kWh/m² at around 30kWh/m², reducing energy consumption and bills up to two-thirds compared with existing UK housing stock (Chatterton, 2015, p.84).

Involvement of users and stakeholders

LILAC is owned by a cooperative, through the innovative equity-based model: Mutual Home Ownership Scheme (MHOS). The MHOS is a leaseholder approach (Chatterton, 2013) where residents purchase shares in the co-operative. The number of shares owned by each member is related in part to their income, and partly according to the size of their property. If someone earn a large income their house becomes more expensive, but another property subsequently becomes cheaper, thus conserving affordability. Affordable housing at LILAC is maintained as no more than 35% of net household income should be spent on housing (Chatterton, 2013; LILAC Coop, 2022a).

Minimum net income levels were set for each different house size to ensure a 35% equity share rate generates enough income to cover the mortgage repayments (Pickerill, 2015). The MHOS owns the homes and land and is made up of the residents who also manage LILAC. Members lease and occupy specific houses or flat from the MHOS. In effect, residents are their own landlords.

The building was financed by a combination of personal members invested capital, a long-term mortgage from the ethical bank Triodos, and a government grant of £420,000 from The Homes and Communities Agency’s Low Carbon Investment Fund, specifically to experiment with ModCell straw construction (Chatterton, 2013; Lawton & Atkinson, 2019). Each member makes monthly payments to the MHOS, who then pays the mortgage – deductions are made for service costs. In 2015, annual household minimum income for a home was set as at least £15,000.

‘Community agreements’ cover areas such as pets, food, communal cooking, use of the common house, management of green spaces, equal opportunities, vulnerable adults, the use of white goods, housing allocation and diversity, and garden upkeep (Chatterton, 2013; LILAC, 2021). “MHOS forms the democratic heart of the project” (Chatterton, 2013). All decisions are made democratically, using templates to generate and discuss proposals, explore pros and cons, generate amendments, and ratify decisions (Chatterton, 2013).

Relationship to urban environment

LILAC is in a highly integrated inner-city locality, situated in an urban neighbourhood of Leeds, on a site that was previously a school. Integrating with the wider community in West Leeds, the common house is used for “local meetings, film nights, meals and gatherings, workshops and has been used as the local polling station” (LILAC Coop, 2022b). LILAC has increased residents feeling of empowerment to participate in social action, working within the wider community to explore issues together and work for change. This has included supporting a local community association, local schools and holding charity and music events (LILAC, 2021).

Behaviour and wellbeing

LILACs community act in the knowledge that an adequate response to climate change and energy reduction takes shifting the way we live, enacting behavioural changes that contribute to a post-carbon transition. Decisions in cohousing are made as a community, rather than individual consumers or households. Residents report a much higher health satisfaction – from 58% to 76% – and life satisfaction – from 58% to 87% – compared to previous accommodation (LILAC, 2021). Both physical and mental health improvements have been reported since moving to the community due to LILAC’s “plentiful greenspace, sustainable travel options, better high air quality and natural light in the homes, greater social interaction and opportunities for socialising with neighbours” (LILAC, 2021). Further benefits of LILAC as a cohousing scheme include increased safety and wellbeing, natural surveillance and support for the elderly, reduced car numbers combined with car separation and car-free home zones to increase safety as well as reducing carbon emissions related to car use (Chatterton, 2013).

S.Furman. ESR2

Read more

->

HOUSEFUL: Els Mestres, Sabadell

Created on 12-03-2025

Innovative Aspects of the Housing Design/Building:

Bloc Els Mestres underwent a major retrofit as part of the EU-funded HOUSEFUL project, integrating innovative circular solutions and services. Tenants were involved through technical systems operation learning and feedback sessions. Tenant engagement methods included interviews and workshops focused on teaching residents how to engage with energy consumption and learning the energy consumption of home systems. As with typical DER, there were four main technical improvements to the building: (1) airtightness, (2) insulation, (3) smart systems, and (4) renewable energies. Circular solutions also incorporated into the retrofit to reduce waste include: (1) reusing the balcony balustrades after raising their height to meet building regulations, (2) recycled wall cladding product, and (3) greywater to be treated using the Nature Based Solution (NBS) of a green wall inside the courtyard.

Construction Characteristics, Materials, and Processes:

After the rehabilitation, the housing block has evolved into a resilient structure with two four-bedroom apartments per floor, spanning the 1st to the 8th floor. Its distinctive design encompasses an array of materials, from natural limestone and cork SATE for insulation to yellow render, terracotta brick, and unobstructed glass panels. With a strategic south-east orientation, the building optimizes natural light, thanks to square windows and cantilevered balconies. Inside, the apartments are designed in a clean, white palette, giving tenants the freedom to infuse their unique style and personal touch.

Energy Performance Characteristics:

Physical deep energy retrofit interventions included: cork external wall insulation; airtightness, fixing holes and fissures, double glazing, and other solutions to reduce thermal coefficient; mechanical ventilation; hydraulic balance valve with differential pressure measurement for the determination of the circulation flow, with insulation; and solar thermal panels, owned by the building owner, together increasing energy efficiency by approximately 50% compared to pre-retrofit. Tenants received technical training on how to use dwelling systems, potentially improving energy efficiency.

Involvement of Users and Other Stakeholders:

The rehabilitation process has involved collaborative decision-making among key stakeholders: LEITAT, non-profit organisation managing and researching sustainable technologies—project co-ordinators; AHC—Housing Agency of Catalonia and building owners; Sabadell Council; WE&B, organised co-creation activities and resident outreach; Housing Europe; members of the tenants’ association; Aiguasol, solar thermal energy; and ITEC, Catalan Institute of Construction and Technology—performed LCAs (life cycle analyses) to decide on cost-effectiveness of circular solutions.

The retrofit project encompassed low levels of tenant consultation and feedback sessions. The importance of managing conflicts that arise during tenant involvement in decision-making processes was recognised. A 'circularity agent' was proposed to teach tenants how to use complex technical systems, potentially fostering in-house expertise.

Relationship to Urban Environment:

Located in Sabadell Sud near the local airport, the block has undergone a significant transformation over the years. It has evolved from an isolated building, the once surrounding fields now transformed into a densely populated urban environment. Notably, it seamlessly integrates into this urban landscape, with a tonally harmonious façade that bathes the surroundings in a warm and visually appealing ambiance. The ground floor is dedicated to the community, fostering a strong connection to the local area and its residents. The nearby pedestrianized streets, adorned with benches, trees, and versatile playground equipment for all age groups, create a welcoming and inclusive atmosphere. This building plays a vital role as it provides accommodation exclusively for social housing residents, contributing to the rich social fabric of the urban community.

S.Furman. ESR2

Read more

->

Mason Place Apartments

Created on 11-12-2023

Mason Place is a permanent supportive housing development in the city of Fort Collins, Colorado, US, developed by Housing Catalyst, that uses trauma-informed design to create a safe and supportive environment for residents. It is a home to individuals who may have been suffered both short and long-term periods of homelessness while ten units are reserved for veterans (Housing Catalyst, 2021; Kimura, 2021). For over five decades, Housing Catalyst has been a cornerstone of the Northern Colorado community, unwavering in its commitment to providing accessible and affordable housing solutions. Through innovative, sustainable, and community-centric approaches, Housing Catalyst has developed and managed over 1,000 affordable homes, becoming the largest property manager in the region (Housing Catalyst, 2021). Housing Catalyst plays a pivotal role in administering housing assistance programs, serving thousands of residents each year. With a steadfast focus on families with children, seniors, individuals with disabilities, and those experiencing homelessness, Housing Catalyst tirelessly strives to make homeownership a reality for all (Housing Catalyst, 2021).

To create Mason Place, Housing Catalyst gave a new purpose to an old movie theatre by designing it with trauma survivors in mind. This resulted in a building with a skylighted atrium, large windows in units and common spaces, live plants, and wooden skirting board to create a calming environment. Case managers (on-site service assistants provided by the Homeward Alliance) worked with residents to develop and implement individualized plans to address their unique needs. This included assistance with finding employment, accessing healthcare, and securing permanent housing. Case managers also provided support and encouragement for residents to develop the skills and helped them to gain confidence (Homeward Alliance, 2021). David Rout, executive director of Homeward Alliance, said:

“When it comes to our community's ongoing effort to make homelessness rare, short-lived and non-recurring, developments like Mason Place are the gold standard. It will immediately provide dozens of our most vulnerable neighbors with a safe place to live and the supportive services they need to stay housed, healthy and happy” (Coloradoan, 2021).

Homeward Alliance, a non-profit organization that provides a continuum of care in Fort Collins, provided two case managers at Mason Place, who worked with individuals and families to develop plans to address their long-term needs, and to help residents with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), such as using the bus system, proper personal hygiene, and cooking, as well as Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs), among them, accessing treatment for mental health issues, applying for a job, and obtaining healthcare benefits. In addition to case management, Homeward Alliance also provided a variety of support services, including mental health services, substance abuse treatment, employment services, and other needed care.

Affordability aspects

The affordability of housing has been a long-standing priority for the city of Fort Collins. As highlighted in the city plan (City of Fort Collins, 2023), and also in the housing strategic plan (City of Fort Collins, 2021), housing affordability is a key element of community liveability. The Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) overlay zones, such as the College/Mason corridor to the South Transit Center are used to encourage higher-density development in areas that are well-served by public transit. These zones typically have additional land use code standards, such as higher density requirements, mixed-use requirements, and pedestrian-friendly design standards. One of the provisions of the TOD is the allowance of one additional story of building height if the project qualifies as an affordable housing development and is south of Prospect Road. This allows the developer to build more units in exchange for 10% of the units overall being affordable to households earning 80% of Area Median Income (AMI) or less. This provision is designed to increase the supply of affordable housing in TOD areas, which are typically located near public transit and other amenities. By allowing developers to build more units in exchange for providing affordable housing, TOD areas become more accessible to lower-income residents. In addition to increasing the supply of affordable housing, TOD can also help to achieve other sustainability goals. For example, encouraging people to live in those areas helps to reduce vehicle miles travelled and air pollution. Overall, the TOD provision is a win-win for both developers and communities. It allows developers to build more units in desirable locations, and it helps to provide inclusive and affordable for all residents (City of Fort Collins, 2021).

As the community continues to grow, a significant portion of the population is struggling to afford stable and healthy housing. Nearly 60% of renters and 20% of homeowners are cost-burdened (City of Fort Collins, 2021)., meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on housing. Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and low-income households are disproportionately affected by this issue, with lower homeownership rates, lower income levels, and higher rates of poverty (City of Fort Collins, 2021). The city facilitates affordable housing to promote mixed-income neighbourhoods and reduce concentrations of poverty. In 2018 Housing Catalyst submitted a funding application to the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority's Low Income Housing Credit programme and the construction started in 2019. Currently, Mason Place provides affordable housing, in form of low-income apartments, and coordinated services to help people stabilize their lives and move forward.

Housing Catalyst works closely together with the National Equity Fund, which is a nonprofit organization that delivers new and innovative financial solutions to expand the creation and preservation of affordable housing. According to the Fund, everyone deserves a safe and affordable place to live. Their vision is that all individuals and families must have access to stable, safe, and affordable homes that provide a foundation for them to reach their full potential (National Equity Fund, 2022). Mason Place houses the disabled and homeless, including military veterans earning up to 30 percent of the area median income, or about $16,150 for a single person.

A.Martin. ESR7

Read more

->

ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

Over the last decades, ESG debt issuance, through green, social or sustainability-linked loans and bonds has become increasingly common. Financial markets have hailed the adoption of ESG indicators as a tool to align capital investments with environmental and social goals, such as the decarbonisation of the social housing stock. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the green debt market has experienced a 50% growth over the last five years (CBI, 2021). However, the lack of clearly established indicators and objectives has tainted the growth of green finance with a series of high-level scandals and accusations of green-washing, unjustified claims of a company’s green credentials. For example, a fraud investigation by German prosecutors into Deutsche Bank’s asset manager, DWS, has found that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments despite this being stated in the fund’s prospectus (Reuters, 2022).

To curb greenwashing and improve transparency and accountability in green investments, the EU has embarked on an ambitious legislative agenda. This includes the first classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities: the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation 2020/852). The Taxonomy is directly linked to the European Commission’s decarbonisation strategy, the Renovation Wave (COM (2020) 662), which relies on a combination of private and public finance to secure the investment needed for the decarbonisation of social housing.

Energy efficiency targets have become increasingly stringent as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its successive recasts (COM(2021)) have been incorporated into national legislation; see for example the French Loi Climate et Resilience (2021-1104, 2021). Consequently, capital expenses for SHOs are set to increase considerably. For example, in the Netherlands, according to a Housing Europe (2020) report, attaining the 2035 energy efficiency targets set by the Dutch government will cost €116bn.

Sustainable finance legislation constitutes an expansion of the financial measures implemented by the EU in recent decades to incentivise energy efficiency standards as well as renovations in the built environment. For more detail on prior EU policies, see Economidou et al. (2020) and Bertoldi et al. (2021). The increased connections between finance and energy performance raise specific questions regarding SHOs’ access to capital markets in light of the shift toward ESG.

The rapidly expanding finance literature on green bonds draws from econometric models to explore the links between investors’ preferences and yields (Fama & French, 2007). This body of literature on asset pricing relies on the introduction of non-pecuniary preferences in investors’ utility functions together with returns and risks to explain fluctuations in the equilibrium price of capital. Drawing from a comparison between green and conventional bonds, Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) find evidence of the former being priced at a premium. Similarly, Zerbib (2019) also shows a low but significant negative yield premium for green bonds resulting from both investors’ environmental preferences and lower risk levels. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (Fatica & Panzica, 2021) documents the dependency of premiums on the issuer with significant estimates for supranational institutions and corporations, but not for financial institutions. While these econometric approaches offer relevant insight into the pricing of green bonds and the incentives for issuers and investors, they do not account for the institutional particularities of social housing, a highly regulated sector usually covered by varying forms of state guarantees and subsidisation (Lawson, 2013).

ESG-labelled debt instruments & Related Legislation

Throughout the last two decades, the term ESG finance has evolved to include a large number of financial vehicles of which green bonds have become the most popular (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). In the social housing sector, ESG comprises a broad array of tools from sustainability-linked loans to less conventional forms of finance such as carbon credits. When it comes to bonds, there is a wide variation in the sustainability credentials among the different types. Broadly speaking, green and social bonds are issued under specific ‘use of proceeds’, which means the funds raised must be used to finance projects producing clear environmental or social benefits. The issuance of these types of bonds requires a sustainable finance framework, which is usually assessed by a third party emitting an opinion on its robustness.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are an alternative to ‘use of proceeds’. Funds raised in this manner are not earmarked for sustainable projects, but can be used for general purposes. SLBs are linked to the attainment of certain company-wide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), for example an average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of “C” in an SHO’s housing stock. These indicators and objectives usually result in a price premium for Sustainable Bonds, or a rebate in interest rates in the case of SLBs or sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021).

While there are international standards for the categorisation of green projects such as the Green Bond Principle or the Climate Bonds Strategy, strict adherence is optional and there are few legally-binding requirements resulting in a large divergence in reporting practices and external auditing. To solve these issues and prevent greenwashing, the EU has been the first regulator to embark on the formulation of a legal framework for green finance through a series of acts targeting the labelling of economic activities, investors, corporations and financial vehicles.

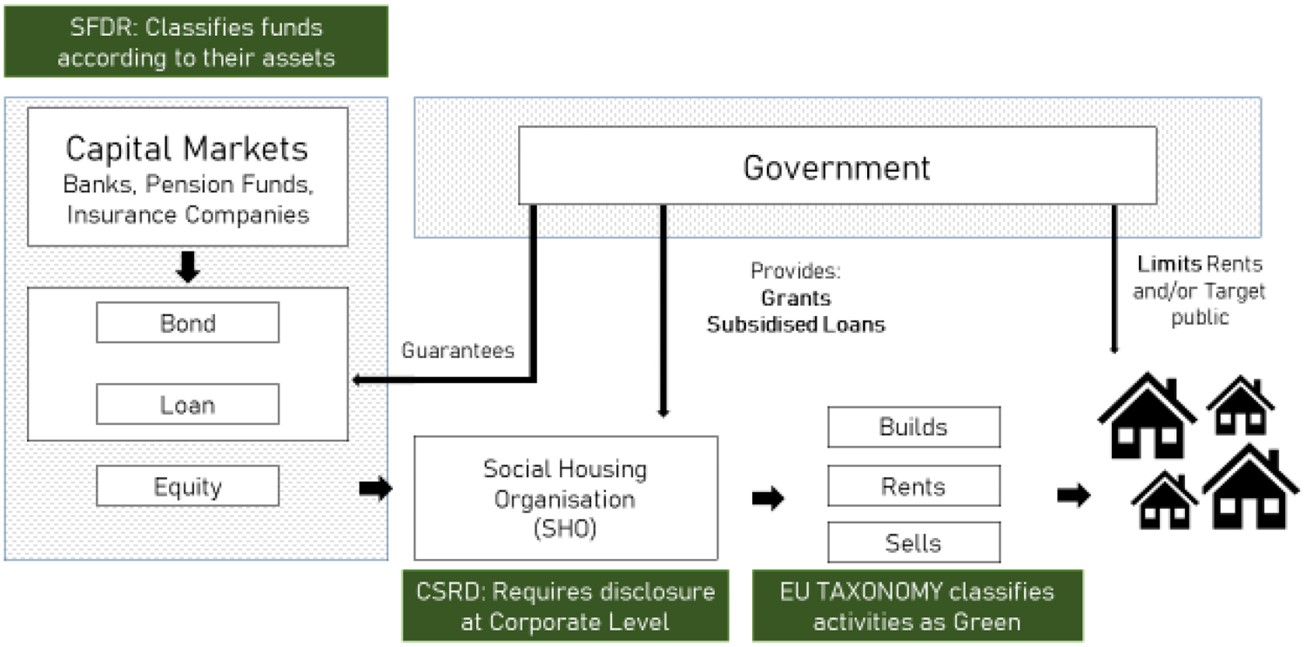

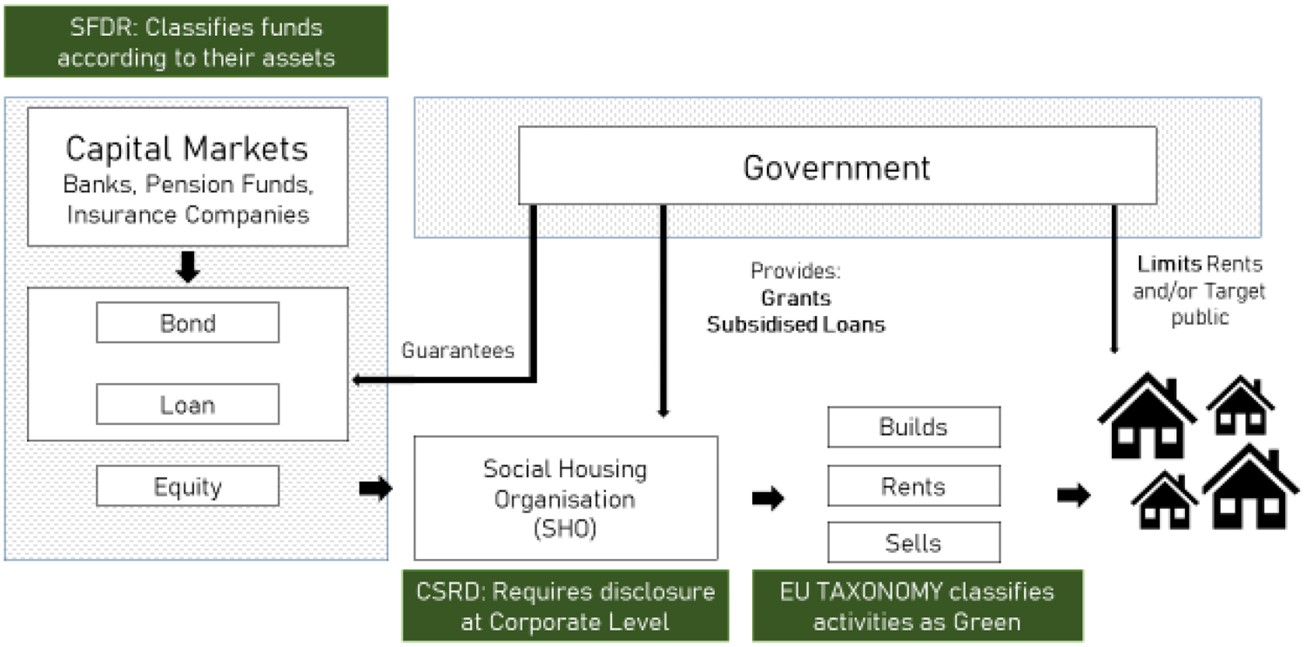

First, the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) is the cornerstone of this new legislation since it classifies economic activities attending to their alignment with the objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD). When it comes to housing, the EU Taxonomy requires specific energy efficiency levels for a project to be deemed ‘taxonomy aligned’. Second, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) mandates ESG reporting on funds, which tend to consist of exchange-traded collections of real assets, bonds or stocks. Funds are required to self-classify under article 6 with no sustainability scope, ‘light green’ article 8 which incorporates some sustainability elements, and article 9 ‘dark green’ for funds only investing in sustainability objectives. Under the SFDR, which came into effect in January 2023, fund managers are required to report the proportion of energy inefficient real estate assets as calculated by a specific formula taking into account the proportion of ‘nearly zero-energy building’, ‘primary energy demand’ and ‘energy performance certificate’ (Conrads, 2022). Third, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)(COM(2021) 189) increases disclosure requirements for corporations along Taxonomy lines. This legislation, which came into effect in 2023, will be progressively rolled out starting from larger and listed companies and expanding to a majority of companies this decade. Provisions have been made for charities and non-profits to be exempt. However, one of the key consequences of disclosure requirements over funds through the SFDR is its waterfall effect; that is the imposition of indirect reporting requirements as investors pass-on their reporting responsibilities to their borrowers. Fourth, the proposed EU Green Bonds Standards (EU-GBS) COM(2021) 391 aims to gear bond proceedings toward Taxonomy-aligned projects and increase transparency through detailed reporting and external reviewing by auditors certified by the European Security Markets Authorities (ESMA). The main objectives of these legislative changes is to create additionality, that is, steer new finance into green activities (see Figure 1).

While this new legislation is poised to increase accountability and transparency, it also aims to encourage a better management of environmental risks. According to a recent report on banking supervision by the European Central Bank (ECB), real estate is one of the major sources of risk exposure for the financial sector (ECB, 2022). This includes both physical risks, those resulting from flooding or drought and, more relevant in this case, transitional risks, that is those derived from changes in legislation such as the EPBD and transposing national legislation. The ECB points to the need for a better understanding of risk transmission channels from real estate portfolios into the financial sector through enhanced data collection and better assessments of energy efficiency, renovation costs and investing capacity. At its most extreme, non-compliance with EU regulations could result in premature devaluation and stranded assets (ECB, 2022).

In short, the introduction of reporting and oversight mechanisms connects legislation on housing’s built fabric, namely the EPBD, to financial circuits. On the one hand, the EU has been strengthening its requirements vis-à-vis energy efficiency over the last decades. The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) suggested the introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by Member States (Economidou et al., 2020), a rationale followed by France and the Netherlands for certain segments of the housing stock. Currently, policy-makers are debating on whether the EPBD’s recast (COM/2021/802) should incorporate MEPS and make decarbonisation an obligation for SHOs across the EU. On the other hand, legislation on green finance aims to produce incentives and oversight over investments in energy efficient renovation and new build, mobilising the private sector to cater to green projects (Renovation Wave (COM(2020) 662)).

A.Fernandez. ESR12

Read more

->

85 Social Housing Units in Cornellà

Created on 26-07-2024

An economic, social and environmental challenge

The architects Marta Peris and José Manuel Toral (P+T) faced the task of developing a proposal for collective housing on a site with social, economic, and environmental challenges. This social housing building won through an architectural competition organised by IMPSOL, a public body responsible for providing affordable housing in the metropolitan area of Barcelona. The block, located in the working-class neighbourhood of Sant Ildefons in Cornellà del Llobregat where the income per capita is €11,550 per year, was constructed on the site of the old Cinema Pisa. Although the cinema had closed down in 2012, the area remained a pivotal point for the community, so the social impact of the new building on the urban fabric and the existing community was of paramount importance.

The competition was won in 2017 and the housing was constructed between 2018 and 2020. The building, comprised of 85 social housing dwellings, covers a surface of 10,000m2 distributed in five floors. Adhering to a stringent budget based on social housing standards, the building offers a variety of dwellings designed to accommodate different household compositions. Family structures are heterogeneous and constantly evolving, with new uses entering the home and intimacy becoming more fluid. In the past, intimacy was primarily associated with a bedroom and its objects, but the concept has become more ambiguous, and now privacy lies in our hands, our phones, and other devices. In response to these emerging lifestyles, the architects envisioned the dwelling as a place to be inhabited in a porous and permeable manner, accommodating these changing needs.

This collective housing is organised around a courtyard. The housing units are conceived as a matrix of connected rooms of equal size, 13 m², totalling 114 rooms per floor and 543 rooms in the entire building. Dwellings are formed by the addition of 5 or 6 rooms, resulting in 18 dwellings per floor, which benefit from cross ventilation and the absence of internal corridors.

While the use of mass timber as an element of the construction was not a requisite of the competition, the architects opted to incorporate this material to enhance the building's degree of industrialisation. A wooden structure supports the building, made of 8,300 m² of timber from the Basque Country. The use of timber would improve construction quality and precision, reduce execution times, and significantly lower CO2 emissions.

De-hierarchisation of housing layouts

The project is conceived from the inside out, emphasising the development of rooms over the aggregation of dwellings. Inspired by the Japanese room of eight tatamis and its underlying philosophy, the architects aimed for adaptability through neutrality. In the Japanese house, rooms are not named by their specific use but by the tatami count, which is related to the human scale (90 x 180 cm). These polyvalent rooms are often connected on all four sides, creating great porosity and a fluidity of movement between them. The Japanese term ma has a similar meaning to room, but it transcends space by incorporating time as well. This concept highlights the neutrality of the Japanese room, which can accommodate different activities at specific times and can be transformed by such uses.

Contrary to traditional typologies of social housing in Spain, which often follow the minimum room sizes for a bedroom of 6, 8, and 10 m2 stipulated in building codes, this building adopted more generous room sizes by reducing living room space and omitting corridors. P+T anticipated that new forms of dwelling would decrease the importance of a large living room and room specialisation. For many decades, watching TV together has been a social activity within families. Increasingly, new devices and technologies are transforming screens into individual sources of entertainment. The architects determined that the minimum size of a room to facilitate ambiguity of use was 3.60 x 3.60m. Moreover, the multiple connections between spaces promote circulation patterns in which the user can wander through the dwelling endlessly. In this way, the rigid grid of the floor plan is transformed into an adaptable layout, allowing for various spatial arrangements and an ‘enfilade’ of rooms that make the space appear larger. Nevertheless, the location of the bathroom and kitchen spaces suggests, rather than imposes, the location of certain uses in their proximities. The open kitchen is located in the central room, acting as a distribution space that replaces the corridors while simultaneously making domestic work visible and challenging gender roles.

By undermining the hierarchical relation between primary and secondary rooms and eradicating the hegemony of the living room, the room distribution facilitates adaptability over time through its ambiguity of use. In this case, flexibility is achieved not by movable walls but by generous rooms that can be appropriated in multiple ways, connected or separated, achieving spatial polyvalency.

Degrees of porosity to enhance social sustainability

The architects believed that to enhance social sustainability, the building should become a support (in the sense of Open Building and Habraken’s theories) that fosters human relations and encounters between neighbours and household members. In this case there was no existing community, so to encourage the creation of such, the inner courtyard becomes the in-between space linking the public and the private realms, and the place from which the residents access to their dwellings. The gabion walls of the courtyard improve the acoustic performance of this semi-private space. P+T promote the idea of a privacy gradient between communal and the private spaces in their projects. In the case of Cornellà, the access to most dwellings from the terraces creates a connection between the communal and the private, suggesting that dwelling entrances act as filters rather than borders. Connecting this terrace to two of the rooms in a dwelling also provides the option for dual access, allowing the independent use of these rooms while favouring long-term adaptability. Inside the dwelling, the omission of corridors and the proliferation of connecting doors between spaces encourage human relationships and makes them indeterminate. This degree of connectedness between spaces and household members is defined by the degree of porosity chosen by the residents. At the same time, the porosity impacts the freedom to appropriate the space, giving greater importance to the furnishing of fixed areas within a space, such as the corners.

Reduction as an environmental strategy

The short distances defined by the non-hierarchical grid facilitated an optimal structural span for a timber structure. Although, the architects had initially proposed a wall-bearing CLT system, the design was optimised for economic viability by collaborating with timber manufacturers once construction started. This allowed the design team to assess the amount of timber and to research how it could be left visible, seeking to take advantage of all its hygrothermal benefits in the dwellings. It is evident that the greater the distance between structural supports, the more flexible the building is. But the greater this distance, the more material is needed for each structural component, and therefore the greater the environmental footprint. As a result of this collaborative optimisation process, two interior supporting rings were incorporated to the post and beam strategy, which significantly increased the adaptability of the building in the long term as well as halving the amount of timber needed. The façade and stair core continued to use wall-bearing CLT components, bracing the structure against wind and reducing the width of the pillars of the interior structure.

The building features galvanised steel connections between columns and girders, ensuring their continuity and facilitating the installation of services through open joints. Additionally, the high degree of industrialisation of the timber components, achieved through computer numerical control (CNC), optimised and ensured precise assembly. This mechanical connection between components permits the future disassembly if necessary, thereby contributing to a circular economy. To meet acoustic and fire safety requirements, a layer of sand and rockwool was placed on top of the CLT slabs of the flooring, between the timber and the screed, separating the dry and the humid works.

The environmental approach focuses on reducing building layers, drawing inspiration from vernacular architecture. However, unlike traditional building techniques which rely on manual labour, P+T employed prefabricated components to leverage the industry’s precision and reduce work, optimising the use of materials. This reductionist strategy enables them to maximise resources, cut costs, and lower emissions. As a result, the amount of timber actually used in the construction was half the amount proposed in the competition. Moreover, they minimised the number of elements and materials used. For example, an efficient use of folds and geometry eliminated the need for handrails, significantly reducing iron usage and lowering the building's overall carbon footprint.

The dwellings in Cornellà have garnered significant interest, receiving 25 awards from national and international organisations since 2021. Frequent visits from industry professionals, developers, architects, tourists and locals, demonstrate how this exemplary building, promoted by a public institution, may lead the way to more public and private developments that push the boundaries of innovation in future housing solutions.

C.Martín. ESR14

Read more

->

Broadwater Farm Urban Design Framework

Created on 26-07-2024

The Broadwater Farm Estate

The estate, built in the full swing of modernism, is a paragon of the movement’s defining characteristics. The building density is notably high compared to the surrounding single-family terraced houses. There is a clear separation between vehicles and pedestrians, with platforms and deck accesses. The ensemble comprises twelve high-rise precast concrete blocks and towers, which extend over a public-owned site of 18 hectares, which is unusually large by today’s standards. Facilities were also provided for residents, offering them the essential amenities. Upon completion in the early 1970s, the estate comprised 1,063 flats and was home to between 3,000 and 4,000 residents.

As was the case with numerous other modernist housing estates across the country, Broadwater Farm was significantly affected by the seminal work of Alice Coleman, Utopia on Trial (1985) on the concept of “defensible space”. Proponents of this theory posited that design had a deterministic impact on crime rates and social malaise in low-income urban communities. Although Coleman's study faced harsh criticism from academics for its questionable methodology and oversimplification of complex social problems (Cozens & Hillier, 2012; Lees & Warwick, 2022), her recommendations led to the implementation of a multi-million-pound government-funded programme for remedial works in thousands of social housing blocks nationwide; known as the DICE (Design Improvement Controlled Experiment) project. Broadwater Farm was targeted by the programme after it attracted considerable attention following the serious riots that occurred at the estate in 1985 (Stoddard, 2011). A number of initiatives were undertaken with the objective of regenerating and improving the quality of the built environment, with the earliest works beginning in 1981. Under the DICE project, a significant number of the overpass decks that connected the estate on the first floor were demolished on the grounds that they were conducive to the formation of poorly lit and isolated areas that were facilitating criminal activity and anti-social behaviour (Severs, 2010).

In the wake of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, new fire safety regulations and inspections have been introduced, resulting in two blocks of flats being deemed unfit for habitation (BBC, 2022). The Large Panel System (LPS), which was commonly used in the 1960s, has been identified as the primary cause for the demolition of the Tangmere and Northolt blocks due to the significant risk of collapse in the event of a fire. These essential repairs will be part of the largest refurbishment project ever undertaken in the estate. It will comprise a combination of retrofitting, redevelopment and infill, resulting in an increase in the number of housing units and a significant enhancement of the urban layout and public spaces across its 83,000 sq. m.

The Urban Design Framework (UDF) is a comprehensive document that sets out a series of actionable and tangible improvements for the estate. Produced by Karakusevic Carson Architects (2022) and commissioned by the Haringey Borough Council, the UDF serves as a masterplan for the ongoing regeneration of the estate. This document is the result of an extensive stakeholder involvement process. It proposes a series of five urban strategies that, taken together, provide a blueprint for holistic regeneration. These strategies account for the short, medium and long-term development of both the estate and its community.

Given the substantial size of the complex, the scale of the surrounding neighbourhood, and the intricate web of relationships within it, long-term planning holds significant importance. These aspects were emphasised through the proposed interventions that enhance the connections between the dwellings and the urban context. The impact of the estate on the surrounding area and the need for a cohesive urban landscape are addressed through designs that integrate the estate into the city fabric, rather than isolating it. The improvement plan includes the construction of new residential units through the redevelopment of the blocks earmarked for demolition and the refurbishment of the remaining blocks. The architectural firm has developed a "bank of projects," a comprehensive repository of proposed interventions arising from engagement with the community as well as a site analysis, which is organised around five core principles: streets, open spaces, ground floors, character, and homes.

Resident engagement

The inhabitants were actively involved in the creation of the UDF. A series of community engagement events, held between 2020 and 2021, provided a platform to gather the voices of residents and enabled planners to better understand their aspirations and needs, identify the key improvements required, and initiate the design process that would incorporate their views into the masterplan. This process was complemented by the establishment of the Community Design Group (CDG), formed by residents and community members who not only expressed a desire, but also demonstrated the capacity, to assume a more active role in the design process. In addition, the council has set up a website that documents and displays the schedule, events, latest news and updates on the ongoing regeneration process. This website provides comprehensive information for residents, the general public, and any interested parties seeking to gain insight into the current status of Broadwater Farm.

Placemaking strategy

In contrast to pervasive narratives about the flawed design of council estates, the spatial qualities and existing sense of belonging within the community were identified as the starting points for the placemaking strategy. The original configuration of the estate was conceived around community facilities and courtyards, which have been retained, augmented, formalised, and linked by a circuit of pedestrian and cycle paths. The deficiencies of the original design, such as the anonymous and segregated ground floor, have been addressed by establishing a network of public spaces that prioritise human scale and facilitate movement throughout the estate. These new public spaces facilitate social interaction, providing areas of activity complemented by indoor amenities and spaces for local retailers. In this way, the ground level becomes an anchor for diverse activities aimed at enhancing the sense of security.

The masterplan revolves around five principles which in turn incorporate a series of strategies:

1. Safe and Healthy Streets: The improved design shifts away from 'streets in the sky' to enhance street accessibility. It promotes intermodal transport with a new bus route into the estate and the addition of cycle lanes. The road network within the estate has been simplified to be more efficient and encourage walking. A "green" street connects key community facilities and green spaces. Overall wayfinding is enhanced through better street lighting, improved block entrances, and designated car-free areas. Part and parcel of reactivating the ground floor is creating opportunities for new activities through a redesign aimed at more efficient parking solutions to meet current needs.

2. Welcoming + Inclusive Open Spaces: Although the estate features several courtyards and open areas, residents have expressed a feeling of being in a “concrete jungle”, as noted in the community brief. The proposed improvements focused on enhancing the existing courtyards to ensure accessibility and facilitate various activities. In addition, a new community park is planned at the heart of the estate as part of the redeveloped area, designed to be a versatile and welcoming space for current and future residents alike. A hierarchy of shared and public spaces has been redesigned to create a seamless transition into and out of the estate. This seamless and unified experience of the public realm is enabled by specific elements such as play areas and seating that allow people of all ages to socialise and interact in an informal yet purposeful manner.

Workshops were conducted with specific population groups, including young women and girls or older residents, to ensure that the future estate will be as inclusive as possible. Key topics such as perceived safety in the communal areas, activities and sports facilities, as well as overall design considerations, were discussed during these sessions.

3. Ground Floors with Activity: A significant design flaw in the existing estate was the poorly lit areas adjacent to the garages that dominated the ground floor of the blocks — a common design feature in residential architecture of the time. Residents involved in the process pointed out the importance of increasing the sense of security when moving around these areas. A street-based design that activates the ground floor by enabling a greater variety of activities was central to the strategy. Alongside a clearer street layout and improved block entrances, bike racks, bin storage, and opportunities for non-residential and community uses were proposed to benefit both residents and the wider community. By repurposing areas previously used mainly for car parking into active spaces and by enhancing frontages with residential, commercial or community spaces, clear thresholds and boundaries are created to promote permeability and smooth transitions. Community facilities and local businesses are strategically located at corners and key activity nodes, facilitating passive surveillance and overlooking the public realm. The choice of materials also contributes to opening up the ground level; glazed lobbies and entrances connect indoor communal areas with adjacent outdoor spaces visually. Similarly, secondary entrances to existing blocks will be used to balance their function and prevent the creation of hidden or less frequented areas. Improved public lighting, new signage and a control system complement these strategies.

4. Broadwater Character & Scale: The architectural style known as Brutalism played a significant role in popularising the 'problem estate' narrative in Britain. This style was embraced by many of the country's modernist architects, leading to its prevalence in the social housing built during that period. Characterised by the predominant use of concrete, this style was celebrated by critic and advocate Reyner Banham for its memorable image, a clear exhibition of structure and honest expression of the material (Boughton, 2018). The monumentality and stark aesthetics of Brutalism provided an ideal setting for experimentation in the vast estates that were built during the latter half of the 20th century. These characteristics are evident in the design of Broadwater Farm.

Broadwater’s design framework acknowledges the latent potential of the existing architecture while addressing issues of materiality, building height, the links and spatial relationships between the infilled and redeveloped areas and the connection between the estate and its surroundings. The boundaries of the estate were revised to address the issue of it being perceived as an isolated entity, which was a common problem with many modernist estates. This was due to the fact that they were often of a particular size and density, which set them apart from their neighbours. In order to create a seamless transition with the surroundings, clear entrances to the estate are proposed, new materials are used that better match those of the vicinity, and a massing strategy is employed to avoid abrupt transitions in building heights.

The character of the estate was approached in a manner reminiscent of Kevin Lynch’s (1964) five elements of the city —paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks—, with particular emphasis on their importance in establishing a sense of place and enhancing the legibility of the urban environment. The proposal has engaged in a meticulous study of the local context, re-signifying existing elements such as the Kenley Tower, which has been retained as the tallest mass in the ensemble, in order to maintain its landmark character.

5. Good Quality Homes: The new blocks, arranged in courtyards that reflect the existing pattern of the estate, will replace the Tangmere and Northolt blocks. They will occupy a privileged position at the heart of the estate and offer an opportunity to transform the overall look of the scheme. These new blocks, complemented by infill development on nearby sites, will result in the creation of 294 new residential units, representing a net increase of 85 homes. The new dwellings, comprising three and four-bedroom family homes, will be managed by the council and rented out at social rates. A significant proportion of residents who participated in the public consultation highlighted the necessity for larger and more spacious accommodation, particularly for large families. In response to these demands, the design of the new flats incorporates larger and more flexible spaces as a key feature. Those who previously resided in the demolished blocks will be given priority for the new homes.

Furthermore, the introduction of new parks, public spaces, workspaces and a new well-being hub, which will house a doctor's surgery and other services, will help create a more active and dynamic ground floor, with activities that enhance the sense of place and welcome pedestrians. The architects have conducted an analysis of potential infill solutions to activate the ground floor, including the addition of one-bedroom flats that fit into the structural grid of the existing blocks. This in turn addresses the need to create a community that includes people of all ages and family types.

Management & Maintenance

The UDF exemplifies how regeneration projects can address current needs while allowing for future adaptations. This people-centred project fosters a sense of ownership through participation, which is crucial for the sustainability of the intervention. Stewardship is key, especially for the new collective spaces being created. Instead of a deterministic design approach, the framework considers what types of spaces can enhance the overall quality of life. It integrates social, economic, and environmental aspects that define the living and working experience in the area. These considerations are captured in the “Strategy for a Sustainable Neighbourhood.”

The bank of projects is a repository of proposed interventions within the project, illustrating the considerable interest in the long-term effects of the regeneration project and the substantial potential for future development. This section of the framework underscores the necessity for the formulation of a phased, structured and comprehensive planning and delivery strategy that allows for flexibility and input from existing and future residents. Consequently, management and maintenance are regarded as integral aspects of the design, alongside other tangible elements of the built environment.

With an approach strongly focused on creating social value and reducing the disruptive effects of regeneration. The architects have worked with the community to develop a masterplan that emphasises the use of existing assets, minimises demolition and establishes a hierarchy of priorities to maximise the positive impact in the long term.

L.Ricaurte. ESR15

Read more

->