Broadwater Farm Urban Design Framework

Created on 20-06-2024 | Updated on 26-07-2024

The Broadwater Farm Estate provides an illustrative example of the ambitious, council-led, large-scale housing production that characterised the post-war years in Britain. This massive high-density modernist housing project in Tottenham, north London, originated from the Borough of Haringey during a period when local councils led extensive housing production initiatives. As is the case with numerous council estates built during this era, the history of Broadwater Farm Estate has been marked by the fluctuations of housing policies, social struggles, and resistance. Some five decades later, and following a series of remedial redevelopment programmes, the estate is on the brink of its most ambitious and comprehensive regeneration project to date.

The design brief, created through active collaboration between architects, residents, the wider community, and the council, seeks to reconcile the concerns and needs of the existing community with the planning for the estate’s future. The proposal entails an increase in densities through the addition of new blocks to replace structurally unsafe ones, the creation of new public spaces, and the refurbishment of existing blocks. The comprehensive regeneration plan, set forth in the Urban Design Framework (UDF), respects the estate's long history by refurbishing and retrofitting wherever feasible, addresses current housing needs with new blocks and infill homes, and revamps the overall appearance of an estate that is home to a resilient community of almost 5,000 residents and represents an emblematic piece of residential architecture in London. This case study outlines the development process and key features of a document that, if materialised, could serve as a blueprint and reference for future social housing regeneration efforts in the UK and Europe.

Architect(s)

Karakusevic Carson Architects

Location

London, United Kingdom

Project (year)

2024 (ongoing)

Construction (year)

1970s

Housing type

Multifamily housing

Urban context

housing estate

Construction system

Industrialised construction

Status

Unbuilt

Description

The Broadwater Farm Estate

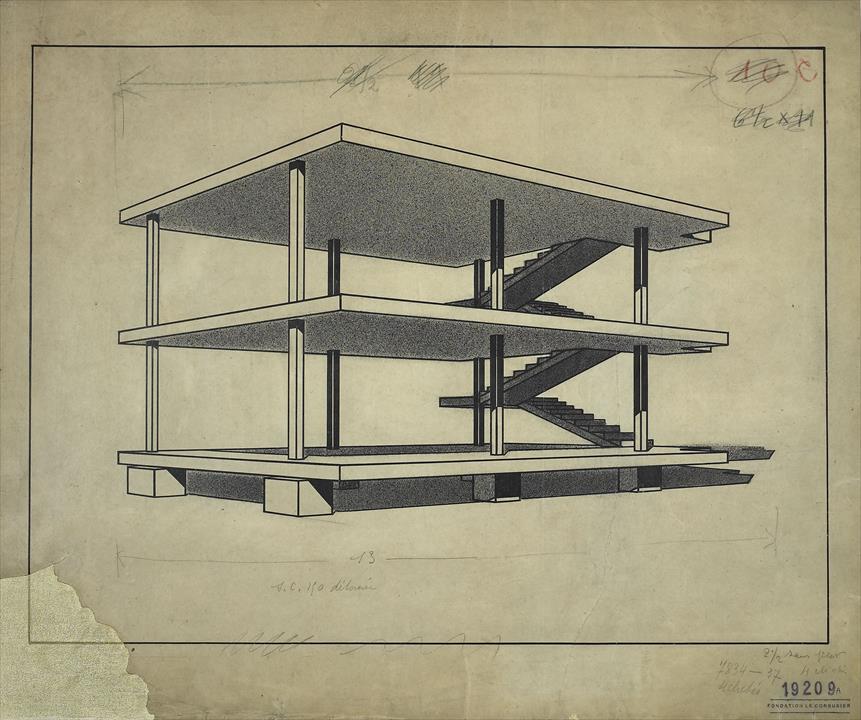

The estate, built in the full swing of modernism, is a paragon of the movement’s defining characteristics. The building density is notably high compared to the surrounding single-family terraced houses. There is a clear separation between vehicles and pedestrians, with platforms and deck accesses. The ensemble comprises twelve high-rise precast concrete blocks and towers, which extend over a public-owned site of 18 hectares, which is unusually large by today’s standards. Facilities were also provided for residents, offering them the essential amenities. Upon completion in the early 1970s, the estate comprised 1,063 flats and was home to between 3,000 and 4,000 residents.

As was the case with numerous other modernist housing estates across the country, Broadwater Farm was significantly affected by the seminal work of Alice Coleman, Utopia on Trial (1985) on the concept of “defensible space”. Proponents of this theory posited that design had a deterministic impact on crime rates and social malaise in low-income urban communities. Although Coleman's study faced harsh criticism from academics for its questionable methodology and oversimplification of complex social problems (Cozens & Hillier, 2012; Lees & Warwick, 2022), her recommendations led to the implementation of a multi-million-pound government-funded programme for remedial works in thousands of social housing blocks nationwide; known as the DICE (Design Improvement Controlled Experiment) project. Broadwater Farm was targeted by the programme after it attracted considerable attention following the serious riots that occurred at the estate in 1985 (Stoddard, 2011). A number of initiatives were undertaken with the objective of regenerating and improving the quality of the built environment, with the earliest works beginning in 1981. Under the DICE project, a significant number of the overpass decks that connected the estate on the first floor were demolished on the grounds that they were conducive to the formation of poorly lit and isolated areas that were facilitating criminal activity and anti-social behaviour (Severs, 2010).

In the wake of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, new fire safety regulations and inspections have been introduced, resulting in two blocks of flats being deemed unfit for habitation (BBC, 2022). The Large Panel System (LPS), which was commonly used in the 1960s, has been identified as the primary cause for the demolition of the Tangmere and Northolt blocks due to the significant risk of collapse in the event of a fire. These essential repairs will be part of the largest refurbishment project ever undertaken in the estate. It will comprise a combination of retrofitting, redevelopment and infill, resulting in an increase in the number of housing units and a significant enhancement of the urban layout and public spaces across its 83,000 sq. m.

The Urban Design Framework (UDF) is a comprehensive document that sets out a series of actionable and tangible improvements for the estate. Produced by Karakusevic Carson Architects (2022) and commissioned by the Haringey Borough Council, the UDF serves as a masterplan for the ongoing regeneration of the estate. This document is the result of an extensive stakeholder involvement process. It proposes a series of five urban strategies that, taken together, provide a blueprint for holistic regeneration. These strategies account for the short, medium and long-term development of both the estate and its community.

Given the substantial size of the complex, the scale of the surrounding neighbourhood, and the intricate web of relationships within it, long-term planning holds significant importance. These aspects were emphasised through the proposed interventions that enhance the connections between the dwellings and the urban context. The impact of the estate on the surrounding area and the need for a cohesive urban landscape are addressed through designs that integrate the estate into the city fabric, rather than isolating it. The improvement plan includes the construction of new residential units through the redevelopment of the blocks earmarked for demolition and the refurbishment of the remaining blocks. The architectural firm has developed a "bank of projects," a comprehensive repository of proposed interventions arising from engagement with the community as well as a site analysis, which is organised around five core principles: streets, open spaces, ground floors, character, and homes.

Resident engagement

The inhabitants were actively involved in the creation of the UDF. A series of community engagement events, held between 2020 and 2021, provided a platform to gather the voices of residents and enabled planners to better understand their aspirations and needs, identify the key improvements required, and initiate the design process that would incorporate their views into the masterplan. This process was complemented by the establishment of the Community Design Group (CDG), formed by residents and community members who not only expressed a desire, but also demonstrated the capacity, to assume a more active role in the design process. In addition, the council has set up a website that documents and displays the schedule, events, latest news and updates on the ongoing regeneration process. This website provides comprehensive information for residents, the general public, and any interested parties seeking to gain insight into the current status of Broadwater Farm.

Placemaking strategy

In contrast to pervasive narratives about the flawed design of council estates, the spatial qualities and existing sense of belonging within the community were identified as the starting points for the placemaking strategy. The original configuration of the estate was conceived around community facilities and courtyards, which have been retained, augmented, formalised, and linked by a circuit of pedestrian and cycle paths. The deficiencies of the original design, such as the anonymous and segregated ground floor, have been addressed by establishing a network of public spaces that prioritise human scale and facilitate movement throughout the estate. These new public spaces facilitate social interaction, providing areas of activity complemented by indoor amenities and spaces for local retailers. In this way, the ground level becomes an anchor for diverse activities aimed at enhancing the sense of security.

The masterplan revolves around five principles which in turn incorporate a series of strategies:

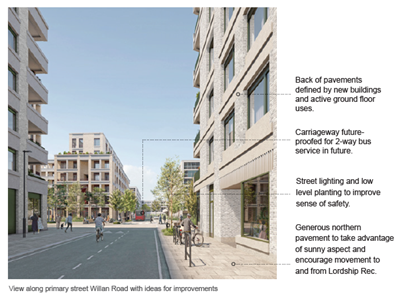

1. Safe and Healthy Streets: The improved design shifts away from 'streets in the sky' to enhance street accessibility. It promotes intermodal transport with a new bus route into the estate and the addition of cycle lanes. The road network within the estate has been simplified to be more efficient and encourage walking. A "green" street connects key community facilities and green spaces. Overall wayfinding is enhanced through better street lighting, improved block entrances, and designated car-free areas. Part and parcel of reactivating the ground floor is creating opportunities for new activities through a redesign aimed at more efficient parking solutions to meet current needs.

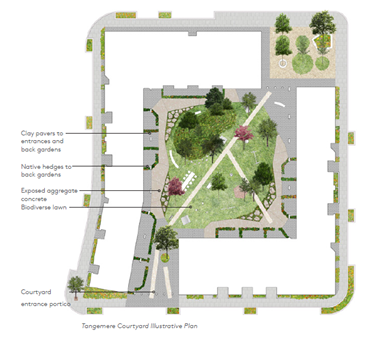

2. Welcoming + Inclusive Open Spaces: Although the estate features several courtyards and open areas, residents have expressed a feeling of being in a “concrete jungle”, as noted in the community brief. The proposed improvements focused on enhancing the existing courtyards to ensure accessibility and facilitate various activities. In addition, a new community park is planned at the heart of the estate as part of the redeveloped area, designed to be a versatile and welcoming space for current and future residents alike. A hierarchy of shared and public spaces has been redesigned to create a seamless transition into and out of the estate. This seamless and unified experience of the public realm is enabled by specific elements such as play areas and seating that allow people of all ages to socialise and interact in an informal yet purposeful manner.

Workshops were conducted with specific population groups, including young women and girls or older residents, to ensure that the future estate will be as inclusive as possible. Key topics such as perceived safety in the communal areas, activities and sports facilities, as well as overall design considerations, were discussed during these sessions.

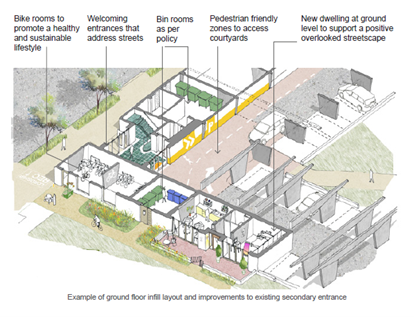

3. Ground Floors with Activity: A significant design flaw in the existing estate was the poorly lit areas adjacent to the garages that dominated the ground floor of the blocks — a common design feature in residential architecture of the time. Residents involved in the process pointed out the importance of increasing the sense of security when moving around these areas. A street-based design that activates the ground floor by enabling a greater variety of activities was central to the strategy. Alongside a clearer street layout and improved block entrances, bike racks, bin storage, and opportunities for non-residential and community uses were proposed to benefit both residents and the wider community. By repurposing areas previously used mainly for car parking into active spaces and by enhancing frontages with residential, commercial or community spaces, clear thresholds and boundaries are created to promote permeability and smooth transitions. Community facilities and local businesses are strategically located at corners and key activity nodes, facilitating passive surveillance and overlooking the public realm. The choice of materials also contributes to opening up the ground level; glazed lobbies and entrances connect indoor communal areas with adjacent outdoor spaces visually. Similarly, secondary entrances to existing blocks will be used to balance their function and prevent the creation of hidden or less frequented areas. Improved public lighting, new signage and a control system complement these strategies.

4. Broadwater Character & Scale: The architectural style known as Brutalism played a significant role in popularising the 'problem estate' narrative in Britain. This style was embraced by many of the country's modernist architects, leading to its prevalence in the social housing built during that period. Characterised by the predominant use of concrete, this style was celebrated by critic and advocate Reyner Banham for its memorable image, a clear exhibition of structure and honest expression of the material (Boughton, 2018). The monumentality and stark aesthetics of Brutalism provided an ideal setting for experimentation in the vast estates that were built during the latter half of the 20th century. These characteristics are evident in the design of Broadwater Farm.

Broadwater’s design framework acknowledges the latent potential of the existing architecture while addressing issues of materiality, building height, the links and spatial relationships between the infilled and redeveloped areas and the connection between the estate and its surroundings. The boundaries of the estate were revised to address the issue of it being perceived as an isolated entity, which was a common problem with many modernist estates. This was due to the fact that they were often of a particular size and density, which set them apart from their neighbours. In order to create a seamless transition with the surroundings, clear entrances to the estate are proposed, new materials are used that better match those of the vicinity, and a massing strategy is employed to avoid abrupt transitions in building heights.

The character of the estate was approached in a manner reminiscent of Kevin Lynch’s (1964) five elements of the city —paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks—, with particular emphasis on their importance in establishing a sense of place and enhancing the legibility of the urban environment. The proposal has engaged in a meticulous study of the local context, re-signifying existing elements such as the Kenley Tower, which has been retained as the tallest mass in the ensemble, in order to maintain its landmark character.

5. Good Quality Homes: The new blocks, arranged in courtyards that reflect the existing pattern of the estate, will replace the Tangmere and Northolt blocks. They will occupy a privileged position at the heart of the estate and offer an opportunity to transform the overall look of the scheme. These new blocks, complemented by infill development on nearby sites, will result in the creation of 294 new residential units, representing a net increase of 85 homes. The new dwellings, comprising three and four-bedroom family homes, will be managed by the council and rented out at social rates. A significant proportion of residents who participated in the public consultation highlighted the necessity for larger and more spacious accommodation, particularly for large families. In response to these demands, the design of the new flats incorporates larger and more flexible spaces as a key feature. Those who previously resided in the demolished blocks will be given priority for the new homes.

Furthermore, the introduction of new parks, public spaces, workspaces and a new well-being hub, which will house a doctor's surgery and other services, will help create a more active and dynamic ground floor, with activities that enhance the sense of place and welcome pedestrians. The architects have conducted an analysis of potential infill solutions to activate the ground floor, including the addition of one-bedroom flats that fit into the structural grid of the existing blocks. This in turn addresses the need to create a community that includes people of all ages and family types.

Management & Maintenance

The UDF exemplifies how regeneration projects can address current needs while allowing for future adaptations. This people-centred project fosters a sense of ownership through participation, which is crucial for the sustainability of the intervention. Stewardship is key, especially for the new collective spaces being created. Instead of a deterministic design approach, the framework considers what types of spaces can enhance the overall quality of life. It integrates social, economic, and environmental aspects that define the living and working experience in the area. These considerations are captured in the “Strategy for a Sustainable Neighbourhood.”

The bank of projects is a repository of proposed interventions within the project, illustrating the considerable interest in the long-term effects of the regeneration project and the substantial potential for future development. This section of the framework underscores the necessity for the formulation of a phased, structured and comprehensive planning and delivery strategy that allows for flexibility and input from existing and future residents. Consequently, management and maintenance are regarded as integral aspects of the design, alongside other tangible elements of the built environment.

With an approach strongly focused on creating social value and reducing the disruptive effects of regeneration. The architects have worked with the community to develop a masterplan that emphasises the use of existing assets, minimises demolition and establishes a hierarchy of priorities to maximise the positive impact in the long term.

Alignment with project research areas

Design, planning and building (Highly related)

- The human factor is the focal point of the overall design strategy. New and existing facilities will be within a 15-minute walk distance of all homes. Walking, cycling or the use of public transport will be encouraged through nature-based interventions and improved infrastructure. These measures not only aim to improve the health and well-being of residents, but also have an impact on the environment.

- A wide range of flats with different sizes and target groups will be created. They will be equipped with passive measures to ensure adequate insulation and energy performance.

- All new homes built as part of the project will remain in the hands of the council, ensuring their social purpose.

Community participation (Highly related)

- Community participation has been extensive. The work carried out with the local community has enabled architects to come up with a holistic design strategy. Workshops, co-design events and involvement activities have been conducted involving hard-to-reach communities. The resulting community brief informed the UDF.

- The online platform set up by the local council in collaboration with an expert third party ensures that the regeneration process is transparent and that all stakeholders are involved. Residents can find out about the project and follow its development both in person and online.

- Local community groups were also involved in the process and even new collectives were formed as a result of the engagement activities. The “Lost Blocks Collective”, for example, is a newly formed group that is now producing a podcast series to share their personal stories and create a new and alternative narrative for life on the estate and in the neighbourhood. All of these groups and residents are expected to be active users of the new community facilities and spaces that are to be built and to play a role in their management.

Policy and financing (Moderately related)

- In order to attain a cost-effective regeneration project without resorting to extensive redevelopment and disruption of the existing community – a common outcome when private sales are the mechanism used to fund the development of social housing – the council and planners opted for a substantial retrofit of the majority of the estate.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

1. No poverty: End poverty in all its forms everywhere (Target: 1.3; 1.4; 1.5)

Broadwater Farm Estate provides affordable and secure housing for almost 5,000 residents. The UDF is a valuable tool to ensure that those homes will remain affordable. The new homes will be made available and the refurbishment of the existing blocks will continue to have a significant impact on residents’ finances. (Highly related)

3. Good health and well-being: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages (Target: 3.4; 3.9)

The interventions proposed by the UDF focus on improving the health and well-being of residents of all ages and the wider community. Nature-based interventions, an improved built environment and public realm and new quality homes are examples of the potential outcomes of the regeneration project. (Highly related)

5. Gender equality: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls (Target: 5.a)

The community involvement strategy emphasised the importance of including the voices of all, especially those of hard-to-reach groups. Young women and girls were the target of workshops to gather their views on what could be improved in the estate. (Moderately related)

7. Affordable and clean energy: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all (Target: 7.1; 7.2; 7.3)

The large-scale refurbishment of the estate that will result from regeneration can have a major impact on the energy consumption of its inhabitants. It is crucial that residents continue to be involved in the process in order to achieve better results in terms of reducing energy poverty and improving consumption behaviour. (Highly related)

11. Sustainable cities and communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable (Target: 11.1; 11.3; 11.7; 11.a; 11.b)

The plans set out in the UDF have taken into account the short, medium and long-term outcomes of the interventions proposed. The extensive engagement that has already taken place and is expected to continue is a promising step towards a sustainable community that is inclusive, cohesive and resilient. (Highly related)

13 Climate action: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts (Target: 13.1; 13.2; 13.3)

The UDF has put a lot of effort into greening the estate. New parks, improved biodiversity, rainwater management and more native plants and trees throughout the site are examples of how the project can have a positive impact on the local environment. (Highly related)

17 Partnerships for the goals: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development (Target: 17.17)

The UDF is the result of the collaborative effort made by the London Borough of Haringey, Karakusevic Carson Architects and, more importantly, residents and the local community. The resulting masterplan and regeneration project will benefit from the joined-up and collaborative environment in which the plan has been created. Enabling residents to have a say in shaping their own environment, supported by the technical expertise of professionals, can have a transformative effect on communities. (Highly related)

References

Boughton, J. (2018). Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing. Verso. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=V77FswEACAAJ

BBC. (2022, December 7). Broadwater Farm Estate to get £130m transformation. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-63878878

Coleman, A., Brown, S., Cottle, L., Marshall, P., Redknap, C., & Sex, R. (1985). Utopia on trial: Vision and reality in planned housing. Hilary Shipman.

Cozens, P., & Hillier, D. (2012). Defensible space. International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-047163-1.00560-9

Karakusevic Carson Architects. (2022). Broadwater Farm Estate Urban Design Framework.

Lees, L., & Warwick, E. (2022). Defensible Space on the Move: Mobilisation in English Housing Policy and Practice. Wiley. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=taNcEAAAQBAJ

Lynch, K. (1964). The image of the city. MIT press.

Severs, D. (2010). Rookeries and no-go estates: St. Giles and Broadwater Farm, or middle-class fear of “non-street” housing. Journal of Architecture, 15(4), 449–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2010.507526

Stoddard, K. (2011, August 8). Anger smoulders in Tottenham: The Broadwater Farm Riots of 1985. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/from-the-archive-blog/2011/aug/08/anger-tottenham-broadwater-riots-1985

Further reading

Video about the structural issues affecting Tangmere and Northolt blocks: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lnDSGDPjY0

Regeneration process:

Related vocabulary

Building Decarbonisation

Collaborative Planning

Community Empowerment

Energy Retrofit

Framework

Housing Retrofit

Participatory Approaches

Placemaking

Social Housing

Social Value

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 06-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 06-03-2024

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 23-05-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 19-06-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 17-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 17-06-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 16-11-2023

Read more ->Blogposts

Architecture enables, not dictates ways of life. Good design doesn’t have to come with a hefty price tag

Posted on 02-11-2023

Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

The “regeneration wave”, hopefully not another missed opportunity to create social value

Posted on 15-07-2023

Summer schools, Reflections

Read more ->

Decoding 'new' housing paradigms

Posted on 13-01-2022

Reflections

Read more ->