LILAC_Low Impact Living Affordable Community_Leeds

Created on 15-11-2024

Innovative aspects of the housing design/building

The model for LILAC is based on the Danish co-housing model: mixing private space with shared spaces to encourage social interaction. A plethora of green spaces include allotments, pond, a shared garden and a children’s play area. Akin to the private self-contained homes, the ‘common house’ includes a communal workshop, office, post room, food cooperative, kitchen, dining space, social space, bike storage, play area, guest rooms and laundry room. The LILAC community benefit from a large number of communal facilities including: a common house with shared laundry, kitchen, reading area and community area; car sharing; pooling household equipment and power tools; sharing common meals twice per week; growing food in the allotment; and looking for provisions in the local area (LILAC Coop, 2022b; ModCell, n.d.). A shared lifestyle whereby resources and amenities are combined, reduces energy use and saves money.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

Constructed under a Design and Build contract (Chatterton, 2015), LILAC boasts an innovative prefabricated ModCell construction that includes a low carbon timber frame insulated with straw-bale. Residents assisted with the labour, collectively adding the straw bale insulation. External walls and interior finishes are in a lime render, increasing benefits from passive solar heating through thermal mass. Air tightness was prioritised during construction, and triple-glazed windows help to decrease heat loss during winter, allowing for Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery Systems (MVHR) to regulate indoor air temperature. Further energy performance characteristics include solar thermal energy collection for space and hot water heating, 1.25kw solar PV array, with an extra 4kw on the common house (LILAC Coop, 2022b).

LILAC features a flood prevention system whereby a sustainable urban drainage system (SUDS) feeds the central pond. Roof rainwater runoff is collected into water butts that are later used to water the gardens. Overflow from water butts enters the central pond, which discharges into the public drainage system at a reduced rate. Furthermore, all ground surfaces of the site are permeable. Biodiversity planting and a permaculture design certificate course were integrated into the design at planning stage.

Major additional spending decisions were made whenever residents believed it would meet their core values and result in long term financial savings (Chatterton, 2015, p.68). Construction costs were therefore higher than the UK average – a 48 sqm one-bedroom flat cost £84,000 to build at a cost of £1,744 per sqm while the average costs in England were £1,200 per sqm. However, the annual heating demand of the homes is far less than the UK average of 140kWh/m² at around 30kWh/m², reducing energy consumption and bills up to two-thirds compared with existing UK housing stock (Chatterton, 2015, p.84).

Involvement of users and stakeholders

LILAC is owned by a cooperative, through the innovative equity-based model: Mutual Home Ownership Scheme (MHOS). The MHOS is a leaseholder approach (Chatterton, 2013) where residents purchase shares in the co-operative. The number of shares owned by each member is related in part to their income, and partly according to the size of their property. If someone earn a large income their house becomes more expensive, but another property subsequently becomes cheaper, thus conserving affordability. Affordable housing at LILAC is maintained as no more than 35% of net household income should be spent on housing (Chatterton, 2013; LILAC Coop, 2022a).

Minimum net income levels were set for each different house size to ensure a 35% equity share rate generates enough income to cover the mortgage repayments (Pickerill, 2015). The MHOS owns the homes and land and is made up of the residents who also manage LILAC. Members lease and occupy specific houses or flat from the MHOS. In effect, residents are their own landlords.

The building was financed by a combination of personal members invested capital, a long-term mortgage from the ethical bank Triodos, and a government grant of £420,000 from The Homes and Communities Agency’s Low Carbon Investment Fund, specifically to experiment with ModCell straw construction (Chatterton, 2013; Lawton & Atkinson, 2019). Each member makes monthly payments to the MHOS, who then pays the mortgage – deductions are made for service costs. In 2015, annual household minimum income for a home was set as at least £15,000.

‘Community agreements’ cover areas such as pets, food, communal cooking, use of the common house, management of green spaces, equal opportunities, vulnerable adults, the use of white goods, housing allocation and diversity, and garden upkeep (Chatterton, 2013; LILAC, 2021). “MHOS forms the democratic heart of the project” (Chatterton, 2013). All decisions are made democratically, using templates to generate and discuss proposals, explore pros and cons, generate amendments, and ratify decisions (Chatterton, 2013).

Relationship to urban environment

LILAC is in a highly integrated inner-city locality, situated in an urban neighbourhood of Leeds, on a site that was previously a school. Integrating with the wider community in West Leeds, the common house is used for “local meetings, film nights, meals and gatherings, workshops and has been used as the local polling station” (LILAC Coop, 2022b). LILAC has increased residents feeling of empowerment to participate in social action, working within the wider community to explore issues together and work for change. This has included supporting a local community association, local schools and holding charity and music events (LILAC, 2021).

Behaviour and wellbeing

LILACs community act in the knowledge that an adequate response to climate change and energy reduction takes shifting the way we live, enacting behavioural changes that contribute to a post-carbon transition. Decisions in cohousing are made as a community, rather than individual consumers or households. Residents report a much higher health satisfaction – from 58% to 76% – and life satisfaction – from 58% to 87% – compared to previous accommodation (LILAC, 2021). Both physical and mental health improvements have been reported since moving to the community due to LILAC’s “plentiful greenspace, sustainable travel options, better high air quality and natural light in the homes, greater social interaction and opportunities for socialising with neighbours” (LILAC, 2021). Further benefits of LILAC as a cohousing scheme include increased safety and wellbeing, natural surveillance and support for the elderly, reduced car numbers combined with car separation and car-free home zones to increase safety as well as reducing carbon emissions related to car use (Chatterton, 2013).

S.Furman. ESR2

Read more

->

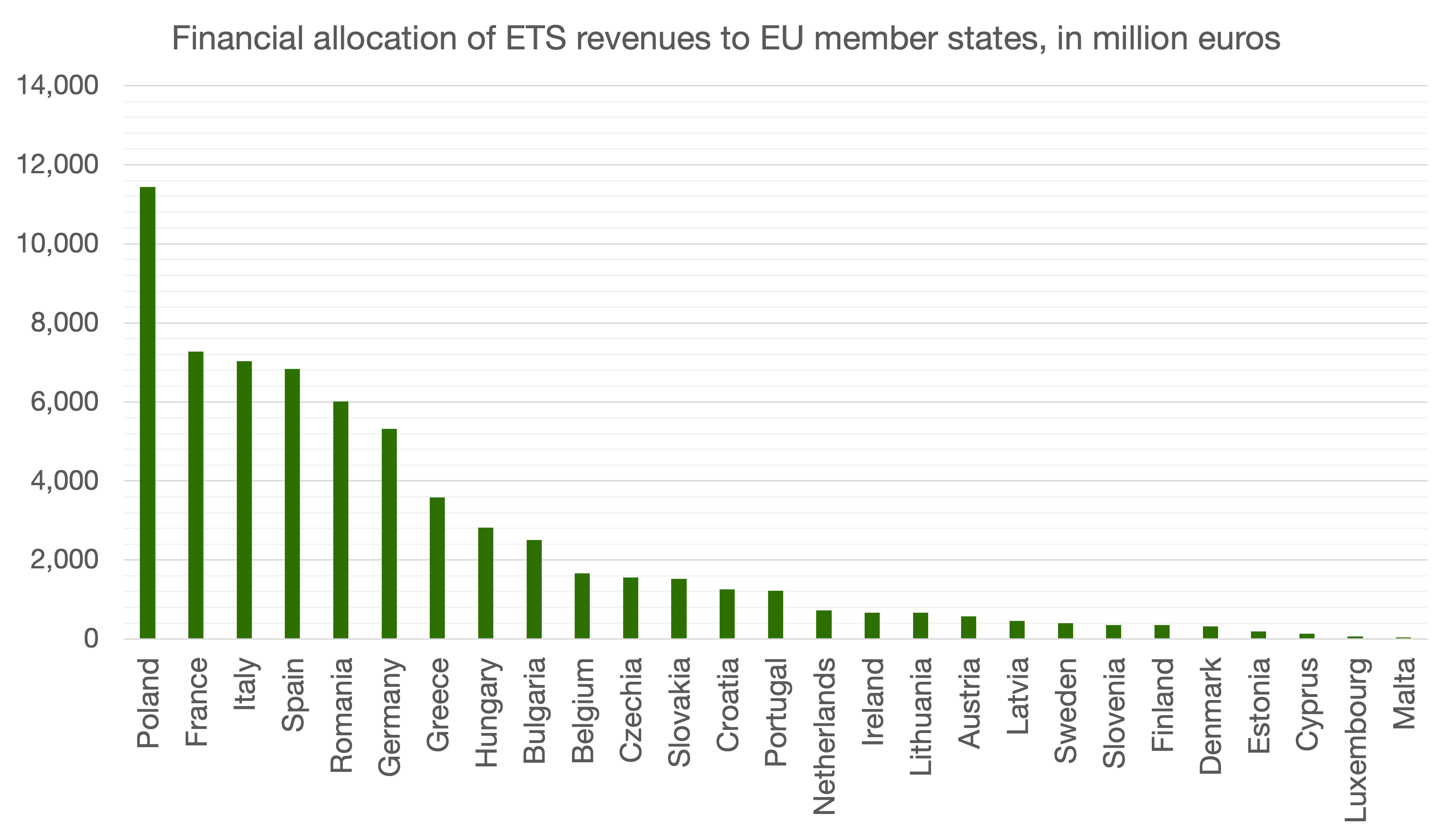

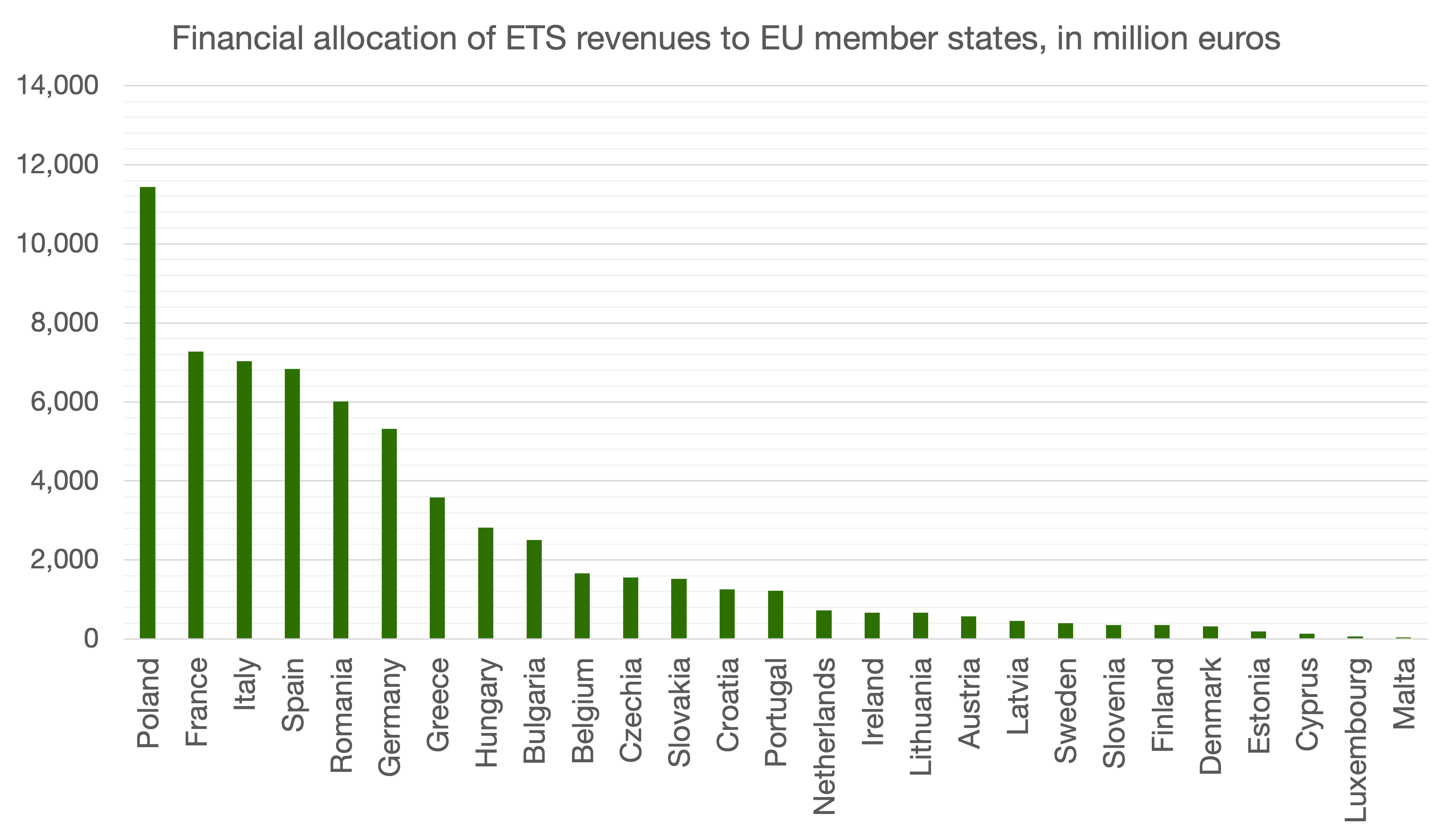

The Social Climate Fund: Materialising Just Transition Principles?

Created on 11-07-2023

The EU's Social Climate Fund (SCF) was officially approved by the European Parliament on 18 April 2023 as part of the broader Green Deal initiative, which seeks to expand the scope of the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) to encompass buildings, transport and other sectors. This extension of the ETS is expected to result in increased energy costs and gasoline prices for households and businesses. To assist vulnerable households, micro-enterprises, and transport users in mitigating the financial impact of these price increases, EU Member States may use resources from the SCF to finance various measures and investments. The SCF will primarily be funded through the revenues generated by the new emissions trading system, with a maximum allocation of €65 bn, which will be supplemented by national contributions. Temporarily established for the period of 2026-2032, the fund aims to provide support during this specified timeframe.

Preliminary Exploration of Merits and Limitations

The initiation of the SCF has received praise from various NGOs advocating for a just transition (WWF, 2022). Supporters highlight its significance in integrating a social dimension into EU climate policies, despite some remaining weaknesses. The SCF’s spending rules are commended for striking a suitable balance between financing structural investments and providing temporary direct income support to vulnerable households. Through the SCF, Member States can finance subsidies that will enable these households to renovate their homes, adopt energy-efficient technologies, and access renewable energy and sustainable transportation. Moreover, various NGOs welcome the requirement for government consultation with subnational administrations and civil society organizations. This could potentially facilitate greater engagement of the target groups in the legislative process. Notably, the SCF also introduces a definition of transport poverty, marking a first in EU policy, and aiding member states to identify those eligible for support (thereby improving recognitional justice).

Regarding the aforementioned weaknesses, there is a range of concerns. Firstly, the projected timeline may pose a limitation. Initiating green investments for vulnerable households only a year before the introduction of carbon pricing may not allow sufficient time for the desired impact. Projects related to energy renovation and improved public mobility infrastructure typically require several years to yield tangible results. Additionally, while Member States are required to include consultation with various stakeholders in their national ‘Social Climate Plans’ (SCPs), the level of participation outlined in the proposed regulation is minimalistic, raising concerns about ensuring procedural justice.

Perceived Importance of Targeting

The legislative text (EU, 2023) underscores the significance of consistent targeting, and Member States are required to furnish comprehensive information regarding the objective of the measure or investment and the specific individuals or groups it aims to address. Additionally, the European Commission expects an elucidation of how the measure or investment will effectively contribute to the accomplishment of the Fund's objectives and its potential to reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

Targeting is deemed particularly crucial with regard to direct income support, as universal energy support tends to generate inflationary pressures, encourage unsustainable behaviour, and yield regressive effects. The legislative text states that is crucial to perceive such support as a temporary measure accompanying the decarbonisation of the housing and transport sectors, rather than a permanent solution that fails to address the fundamental causes of energy poverty and transport poverty. Thus, this support should exclusively target the direct consequences of including greenhouse gas emissions from buildings and road transport under the purview of Directive 2003/87/EC, without encompassing electricity or heating costs related to power and heat production covered by the same directive. As stated, "recipients of direct income support should be targeted, as members of a general group of recipients, by measures and investments aimed at effectively lifting those recipients out of energy poverty and transport poverty" (EU, 2023: p.4).

The share of the SCF designated for renovation projects should also be specifically directed at the vulnerable households and transport users who are already receiving direct income support. SCPs are allowed to extend support to both public and private entities, including social housing providers and public-private cooperatives, in developing and providing affordable energy efficiency solutions and suitable funding mechanisms that align with the social objectives of the Fund. This support could include ‘financial assistance’ or even ‘fiscal incentives’, which poses the question of how lenient should the approach of the European Commission be towards the state support of social housing organisations, given the tensions that have emerged in the past (Gruis & Elsinga, 2014).

Ex Ante and Ex Post Assessment of Social Climate Plans

EU Member States are required to submit national Social Climate Plans (SCPs) no later than 30 June 2025, so that they can be given “careful and timely consideration”. The plans should encompass an investment component that promotes the long-term solution of reducing reliance on fossil fuels, potentially incorporating additional measures, such as temporary direct income support, to alleviate any immediate adverse effects on income.

The primary objectives of these plans must be twofold. Firstly, they should provide vulnerable households, vulnerable micro-enterprises, and vulnerable transport users with the necessary resources to enable them to finance and undertake investments in energy efficiency, the decarbonisation of heating and cooling systems, the adoption of zero- and low-emission vehicles, and sustainable mobility. This support may be provided through mechanisms such as vouchers, subsidies, or zero-interest loans. Secondly, the plans should mitigate the impact of rising fossil fuel costs on the most vulnerable segments of society, thus fighting energy poverty and transport poverty during the transitional phase until the aforementioned investments have been implemented.

The legislative text contains comprehensive information concerning the criteria utilised to assess the SCPs upon submission and evaluation after implementation. The set of ‘result indicators’ that are specifically relevant to the 'building sector' can be found in the table accompanying this case study. Time will tell whether this framework is sufficient to ensure that besides ‘recognitional justice’ and ‘procedural justice’, the SCF will make sure that the European Green Deal delivers ‘distributive justice’.

T.Croon. ESR11

Read more

->

Mason Place Apartments

Created on 11-12-2023

Mason Place is a permanent supportive housing development in the city of Fort Collins, Colorado, US, developed by Housing Catalyst, that uses trauma-informed design to create a safe and supportive environment for residents. It is a home to individuals who may have been suffered both short and long-term periods of homelessness while ten units are reserved for veterans (Housing Catalyst, 2021; Kimura, 2021). For over five decades, Housing Catalyst has been a cornerstone of the Northern Colorado community, unwavering in its commitment to providing accessible and affordable housing solutions. Through innovative, sustainable, and community-centric approaches, Housing Catalyst has developed and managed over 1,000 affordable homes, becoming the largest property manager in the region (Housing Catalyst, 2021). Housing Catalyst plays a pivotal role in administering housing assistance programs, serving thousands of residents each year. With a steadfast focus on families with children, seniors, individuals with disabilities, and those experiencing homelessness, Housing Catalyst tirelessly strives to make homeownership a reality for all (Housing Catalyst, 2021).

To create Mason Place, Housing Catalyst gave a new purpose to an old movie theatre by designing it with trauma survivors in mind. This resulted in a building with a skylighted atrium, large windows in units and common spaces, live plants, and wooden skirting board to create a calming environment. Case managers (on-site service assistants provided by the Homeward Alliance) worked with residents to develop and implement individualized plans to address their unique needs. This included assistance with finding employment, accessing healthcare, and securing permanent housing. Case managers also provided support and encouragement for residents to develop the skills and helped them to gain confidence (Homeward Alliance, 2021). David Rout, executive director of Homeward Alliance, said:

“When it comes to our community's ongoing effort to make homelessness rare, short-lived and non-recurring, developments like Mason Place are the gold standard. It will immediately provide dozens of our most vulnerable neighbors with a safe place to live and the supportive services they need to stay housed, healthy and happy” (Coloradoan, 2021).

Homeward Alliance, a non-profit organization that provides a continuum of care in Fort Collins, provided two case managers at Mason Place, who worked with individuals and families to develop plans to address their long-term needs, and to help residents with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), such as using the bus system, proper personal hygiene, and cooking, as well as Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs), among them, accessing treatment for mental health issues, applying for a job, and obtaining healthcare benefits. In addition to case management, Homeward Alliance also provided a variety of support services, including mental health services, substance abuse treatment, employment services, and other needed care.

Affordability aspects

The affordability of housing has been a long-standing priority for the city of Fort Collins. As highlighted in the city plan (City of Fort Collins, 2023), and also in the housing strategic plan (City of Fort Collins, 2021), housing affordability is a key element of community liveability. The Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) overlay zones, such as the College/Mason corridor to the South Transit Center are used to encourage higher-density development in areas that are well-served by public transit. These zones typically have additional land use code standards, such as higher density requirements, mixed-use requirements, and pedestrian-friendly design standards. One of the provisions of the TOD is the allowance of one additional story of building height if the project qualifies as an affordable housing development and is south of Prospect Road. This allows the developer to build more units in exchange for 10% of the units overall being affordable to households earning 80% of Area Median Income (AMI) or less. This provision is designed to increase the supply of affordable housing in TOD areas, which are typically located near public transit and other amenities. By allowing developers to build more units in exchange for providing affordable housing, TOD areas become more accessible to lower-income residents. In addition to increasing the supply of affordable housing, TOD can also help to achieve other sustainability goals. For example, encouraging people to live in those areas helps to reduce vehicle miles travelled and air pollution. Overall, the TOD provision is a win-win for both developers and communities. It allows developers to build more units in desirable locations, and it helps to provide inclusive and affordable for all residents (City of Fort Collins, 2021).

As the community continues to grow, a significant portion of the population is struggling to afford stable and healthy housing. Nearly 60% of renters and 20% of homeowners are cost-burdened (City of Fort Collins, 2021)., meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on housing. Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and low-income households are disproportionately affected by this issue, with lower homeownership rates, lower income levels, and higher rates of poverty (City of Fort Collins, 2021). The city facilitates affordable housing to promote mixed-income neighbourhoods and reduce concentrations of poverty. In 2018 Housing Catalyst submitted a funding application to the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority's Low Income Housing Credit programme and the construction started in 2019. Currently, Mason Place provides affordable housing, in form of low-income apartments, and coordinated services to help people stabilize their lives and move forward.

Housing Catalyst works closely together with the National Equity Fund, which is a nonprofit organization that delivers new and innovative financial solutions to expand the creation and preservation of affordable housing. According to the Fund, everyone deserves a safe and affordable place to live. Their vision is that all individuals and families must have access to stable, safe, and affordable homes that provide a foundation for them to reach their full potential (National Equity Fund, 2022). Mason Place houses the disabled and homeless, including military veterans earning up to 30 percent of the area median income, or about $16,150 for a single person.

A.Martin. ESR7

Read more

->

Rural Studio

Created on 16-01-2024

“Theory and practice are not only interwoven with one’s culture but with the responsibility of shaping the environment, of breaking up social complacency, and challenging the power of the status quo.”

– Sambo Mockbee

Overview – The (Hi)Story of Rural Studio

Rural Studio is an off-campus, client-driven, design & build & place-based research studio located in the town of Newbern in Hale County in rural Alabama, and part of the curriculum of the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture of Auburn University. It was first conceptualised by Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee and D.K. Ruth as both an answer to the lack of ethical backbone in architectural education and a critique on the separation of theory and practice illustrated through the curriculum (Freear et al., 2013; Jones & Card, 2011). Both of these reasons mirrored and reinforced the way architecture was practised in the professional world in the early 1990s when, following the dominance of post-modernism, US architects were more preoccupied with matters of aesthetics and style, rather than the social and environmental aspects of their work (Oppenheimer Dean, 2002). Mockbee and Ruth aspired to create a learning environment and shape a pedagogy where students would be introduced to a real-world setting, combining theory with hands-on work and at the same time inscribing incremental, positive change on the Hale County underserved communities.

This incremental change is enabled by three main factors: (1) Auburn University’s commitment to providing stable financial support to the studio, paired with the various sponsorships that the studio receives from individual benefactors, (2) the broad network of collaborations that have been established over the years including local governing officials, external professional experts and consultants, non-profit organisations, schools, and community groups, among others, and (3) the studio’s permanent presence -and the subsequent accountability this presence fosters- in Hale County.

Unlike most design-and-build activities and programmes that adopt a “live” approach (i.e. work with/alongside real stakeholders, in real settings), Rural Studio has continuously implemented various types of projects ranging from housing and parks to community activities (e.g. farming and cooking), with five completed projects per year in Newbern and the broader Hale County area since its launching in 1993 (Freear et al., 2013; Stagg & McGlohn, 2022).

Studio structure and learning objectives

Within the Rural Studio, there are two distinct design-and-build programmes addressing third-year and fifth-year undergraduate students. As currently designed, the third-year programme primarily focuses on sharpening technical skills and exploring the process of transitioning from paper to the building site. In contrast, the fifth-year programme places greater emphasis on the social and organizational aspects of a project. Students may opt to join the Rural Studio activities either once during their third of fifth year, or twice, after spending their first two years on campus and having acquired a solid foundation in the basic skills of an architect.

Third-year programme

The third-year programme accommodates up to 16 students per semester, inviting them to reside and work in Newbern on the construction of a wooden house using platform frame construction. Until 2009, the fall semester focused on design, from conception to technical details, while the spring semester concentrated on construction, culminating in the handover of the completed project to clients or future users. However, several issues called for a profound restructuring, such as the uneven distribution of skills (with students specializing in either design or construction, rarely both), a lack of a continuous knowledge transfer from past to current projects, and students’ limited experience in collaborating with larger teams.

In its current iteration, the third-year programme is dedicated to refining technical skills – such as understanding the structural and natural properties of wood- by implementing an already designed project in phases, while complementing this process with parallel modules on building a knowledge base(Freear et al., 2013; Rural Studio, n.d.).

Seminar in aspects of design – students delve deeper in the history of the built environment of the local context, as well as the international history of wooden buildings.

“Dessein” – in this furniture-making course, students focus heavily on sharpening their wood-working skills by recreating chairs designed by well-known modernist architects.

Fifth-year programme

The fifth-year programme consists of up to 12 students, organized into teams of four, who dedicate a full academic year on a community-focused design-and-build project. These projects, collaboratively chosen by the Rural Studio teaching team and local community representatives, ensure alignment with residents’ needs and programmatic suitability for future users. The programme is student-led, requiring participants to engage in client negotiations, manage financial and material resources, and navigate the local socio-political landscape, among other tasks. Projects can be either set up to be concluded within the nine-month academic year or compartmentalized into several phases, spanning several years. In case of the latter, students are invited to stay a second year, overseeing project progress or completion, if they wish, and become mentors to the next group of fifth-year students.

Curriculum and learning Outcomes

In the Rural studio, “students learn by researching, exploring, observing, questioning, drawing, critiquing, designing, and making” In the Rural studio, “students learn by researching, exploring, observing, questioning, drawing, critiquing, designing, and making” (Freear et al., 2013, p. 34). The annual schedules, or “drumbeats,” as they are called, serve to organise and frame the activities throughout each semester. These activities are designed to enhance the skills and knowledge of students, encompassing technical and practical aspects (such as workshops on building codes, structural engineering, graphic design, and woodworking), theoretical understanding (including lectures and idea exchange sessions with invited experts), and communication skills (involving community presentations and midterm reviews). These activities are conducted in a manner that fosters a team-building approach, with creative elements like the Halloween review conducted in fancy dress, and using food as a unifying element.

In terms of learning outcomes, there are four main categories identified*:

Analysis & Synthesis (researching, exploring, observing, questioning). Students learn how to identify, analyse and navigate the parameters that can influence a design-and-build process and lay out a course of action taking everything they have identified into account.

Design & Construction (drawing, designing, making). Students learn how to navigate a project from conception to construction, and develop a deep understanding of construction technologies, environmental and structural systems, as well as the necessary technical skills to perform relevant tasks.

Teamwork & Management (exploring, questioning, critiquing, designing, making). Students learn how to work in large teams, prioritise and allocate tasks, voice their opinion, negotiate, and manage human and material resources.

Ethos & Responsibility (observing, questioning, critiquing). Through place-based immersion in the local community over the span of 4 to 9 months, students get a deeper understanding of their own role and responsibility as architects within the local sustainable development, especially in contexts of crises, and learn how to trace and assess the socio-political, financial and environmental factors that influence a project’s lifespan.

*author’s own assessment and categorisation, based on relevant readings

Context of operations: Hale County, AL

Hale County, located in Alabama, is a black, working-class area and ranks as the second poorest county in the state (Oppenheimer Dean & Hursley, 2005). Historically, southern states like Alabama and Mississippi have been either the locus of an aestheticisation of the rural life and traditions of the past, especially in popular culture (Cox, 2011), or regarded as socially “backward”, marked by elevated levels of social tension, including discriminatory, racist and white supremacist attitudes (Bateman, 2023). Since the decline in cotton production, which began shortly after the American Civil War, Hale County has faced increasing precarity, with its the local economy heavily reliant on low-wage agricultural industries, like dairy. Given the predominant home-ownership culture in the USA and insufficient welfare safety-nets, the poorest members of communities like Hale County are grappling with urgent housing and living issues, resulting in a sizeable portion of the population facing homelessness or residing in precarious conditions, such as trailer parks (Freear et al., 2013).

Rural Studio provides students from other areas of Alabama and beyond, often hailing from middle-class families, with an opportunity to engage with and be exposed to the harsh realities of a version of the USA they may not have encountered or interacted with before.

Notable initiatives and projects

20k House

Initiated in 2005, the 20K House programme engage students in the creation of affordable housing prototypes tailored to the needs and financial capacity of prospective clients: 20,000 USD is the rough amount a minimum wage worker in the USA can receive as a mortgage. Beyond the immediate provision of housing, the programme aspires to draw academic interest in “well-designed houses for everyone” (Freear et al., 2013, p. 202). Additionally, the initiative incorporates post-occupancy evaluations as integral components of both the pedagogical approach and the continuous improvement of services provided to the local community.

Front Porch Initiative

Launched in 2019, this program revolves around the pressing issue of insufficient housing. Its primary goal is to establish an adaptable, scalable, and robust delivery system for high-quality, well-designed homes designated as real property. The design process takes into account the overall costs of homeownership over time, addressing specifically matters of well-being, efficiency and durability. (Rural Studio, n.d.; Stagg & McGlohn, 2022)

Rural Studio Farm

As part of the Newbern strategic plan, the Rural Studio Farm project seeks to immerse students in the realities of food production, exploring its social, cultural, financial, and environmental implications. Simultaneously, the project addresses the rapid decline in local food production in West Alabama (Freear et al., 2013; Rural Studio, n.d.).

E.Roussou. ESR9

Read more

->

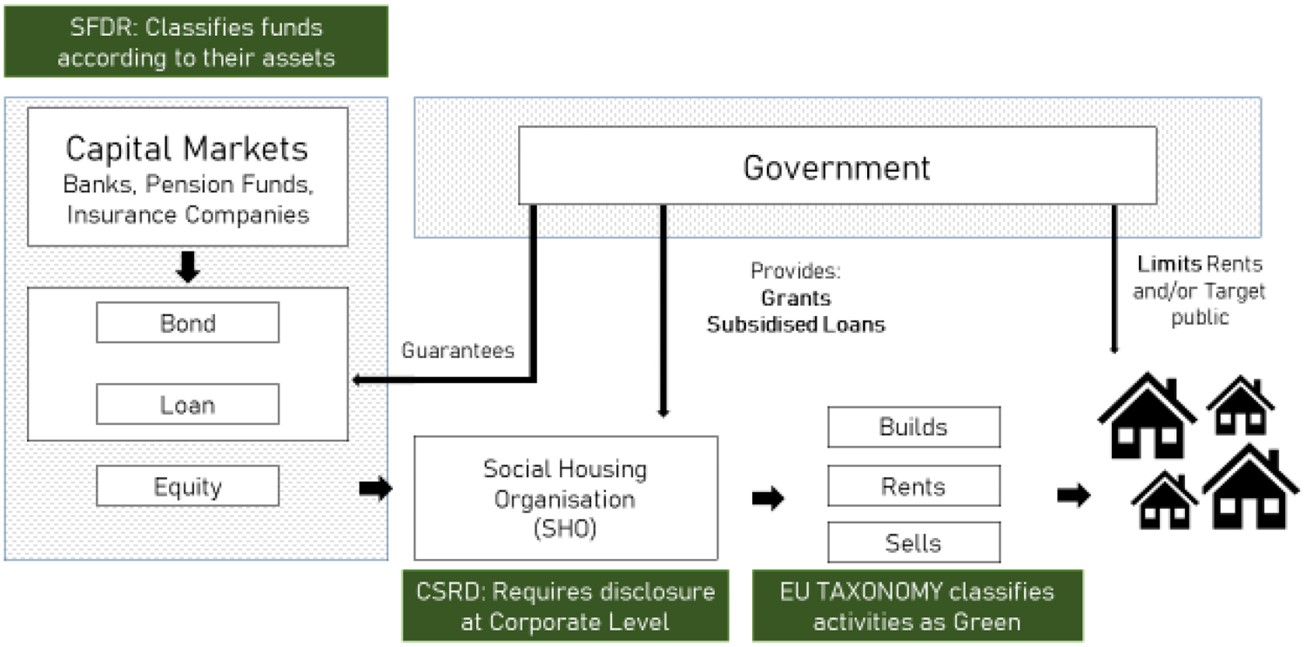

ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

Over the last decades, ESG debt issuance, through green, social or sustainability-linked loans and bonds has become increasingly common. Financial markets have hailed the adoption of ESG indicators as a tool to align capital investments with environmental and social goals, such as the decarbonisation of the social housing stock. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the green debt market has experienced a 50% growth over the last five years (CBI, 2021). However, the lack of clearly established indicators and objectives has tainted the growth of green finance with a series of high-level scandals and accusations of green-washing, unjustified claims of a company’s green credentials. For example, a fraud investigation by German prosecutors into Deutsche Bank’s asset manager, DWS, has found that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments despite this being stated in the fund’s prospectus (Reuters, 2022).

To curb greenwashing and improve transparency and accountability in green investments, the EU has embarked on an ambitious legislative agenda. This includes the first classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities: the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation 2020/852). The Taxonomy is directly linked to the European Commission’s decarbonisation strategy, the Renovation Wave (COM (2020) 662), which relies on a combination of private and public finance to secure the investment needed for the decarbonisation of social housing.

Energy efficiency targets have become increasingly stringent as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its successive recasts (COM(2021)) have been incorporated into national legislation; see for example the French Loi Climate et Resilience (2021-1104, 2021). Consequently, capital expenses for SHOs are set to increase considerably. For example, in the Netherlands, according to a Housing Europe (2020) report, attaining the 2035 energy efficiency targets set by the Dutch government will cost €116bn.

Sustainable finance legislation constitutes an expansion of the financial measures implemented by the EU in recent decades to incentivise energy efficiency standards as well as renovations in the built environment. For more detail on prior EU policies, see Economidou et al. (2020) and Bertoldi et al. (2021). The increased connections between finance and energy performance raise specific questions regarding SHOs’ access to capital markets in light of the shift toward ESG.

The rapidly expanding finance literature on green bonds draws from econometric models to explore the links between investors’ preferences and yields (Fama & French, 2007). This body of literature on asset pricing relies on the introduction of non-pecuniary preferences in investors’ utility functions together with returns and risks to explain fluctuations in the equilibrium price of capital. Drawing from a comparison between green and conventional bonds, Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) find evidence of the former being priced at a premium. Similarly, Zerbib (2019) also shows a low but significant negative yield premium for green bonds resulting from both investors’ environmental preferences and lower risk levels. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (Fatica & Panzica, 2021) documents the dependency of premiums on the issuer with significant estimates for supranational institutions and corporations, but not for financial institutions. While these econometric approaches offer relevant insight into the pricing of green bonds and the incentives for issuers and investors, they do not account for the institutional particularities of social housing, a highly regulated sector usually covered by varying forms of state guarantees and subsidisation (Lawson, 2013).

ESG-labelled debt instruments & Related Legislation

Throughout the last two decades, the term ESG finance has evolved to include a large number of financial vehicles of which green bonds have become the most popular (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). In the social housing sector, ESG comprises a broad array of tools from sustainability-linked loans to less conventional forms of finance such as carbon credits. When it comes to bonds, there is a wide variation in the sustainability credentials among the different types. Broadly speaking, green and social bonds are issued under specific ‘use of proceeds’, which means the funds raised must be used to finance projects producing clear environmental or social benefits. The issuance of these types of bonds requires a sustainable finance framework, which is usually assessed by a third party emitting an opinion on its robustness.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are an alternative to ‘use of proceeds’. Funds raised in this manner are not earmarked for sustainable projects, but can be used for general purposes. SLBs are linked to the attainment of certain company-wide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), for example an average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of “C” in an SHO’s housing stock. These indicators and objectives usually result in a price premium for Sustainable Bonds, or a rebate in interest rates in the case of SLBs or sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021).

While there are international standards for the categorisation of green projects such as the Green Bond Principle or the Climate Bonds Strategy, strict adherence is optional and there are few legally-binding requirements resulting in a large divergence in reporting practices and external auditing. To solve these issues and prevent greenwashing, the EU has been the first regulator to embark on the formulation of a legal framework for green finance through a series of acts targeting the labelling of economic activities, investors, corporations and financial vehicles.

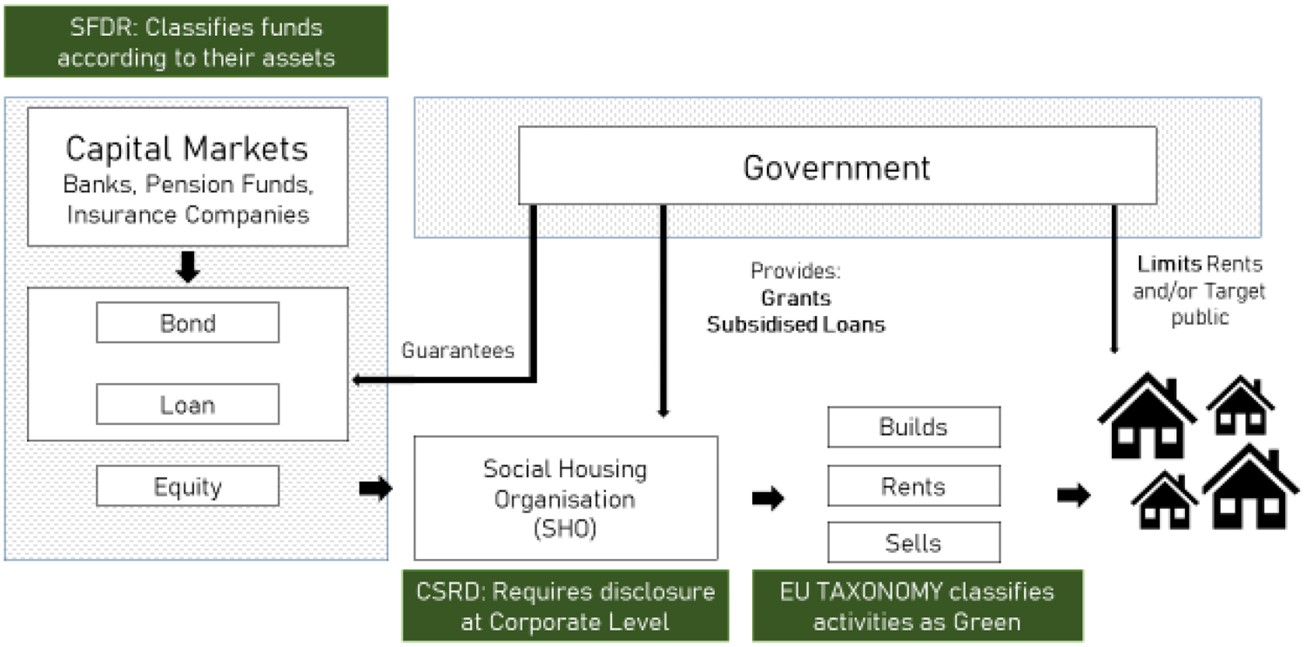

First, the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) is the cornerstone of this new legislation since it classifies economic activities attending to their alignment with the objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD). When it comes to housing, the EU Taxonomy requires specific energy efficiency levels for a project to be deemed ‘taxonomy aligned’. Second, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) mandates ESG reporting on funds, which tend to consist of exchange-traded collections of real assets, bonds or stocks. Funds are required to self-classify under article 6 with no sustainability scope, ‘light green’ article 8 which incorporates some sustainability elements, and article 9 ‘dark green’ for funds only investing in sustainability objectives. Under the SFDR, which came into effect in January 2023, fund managers are required to report the proportion of energy inefficient real estate assets as calculated by a specific formula taking into account the proportion of ‘nearly zero-energy building’, ‘primary energy demand’ and ‘energy performance certificate’ (Conrads, 2022). Third, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)(COM(2021) 189) increases disclosure requirements for corporations along Taxonomy lines. This legislation, which came into effect in 2023, will be progressively rolled out starting from larger and listed companies and expanding to a majority of companies this decade. Provisions have been made for charities and non-profits to be exempt. However, one of the key consequences of disclosure requirements over funds through the SFDR is its waterfall effect; that is the imposition of indirect reporting requirements as investors pass-on their reporting responsibilities to their borrowers. Fourth, the proposed EU Green Bonds Standards (EU-GBS) COM(2021) 391 aims to gear bond proceedings toward Taxonomy-aligned projects and increase transparency through detailed reporting and external reviewing by auditors certified by the European Security Markets Authorities (ESMA). The main objectives of these legislative changes is to create additionality, that is, steer new finance into green activities (see Figure 1).

While this new legislation is poised to increase accountability and transparency, it also aims to encourage a better management of environmental risks. According to a recent report on banking supervision by the European Central Bank (ECB), real estate is one of the major sources of risk exposure for the financial sector (ECB, 2022). This includes both physical risks, those resulting from flooding or drought and, more relevant in this case, transitional risks, that is those derived from changes in legislation such as the EPBD and transposing national legislation. The ECB points to the need for a better understanding of risk transmission channels from real estate portfolios into the financial sector through enhanced data collection and better assessments of energy efficiency, renovation costs and investing capacity. At its most extreme, non-compliance with EU regulations could result in premature devaluation and stranded assets (ECB, 2022).

In short, the introduction of reporting and oversight mechanisms connects legislation on housing’s built fabric, namely the EPBD, to financial circuits. On the one hand, the EU has been strengthening its requirements vis-à-vis energy efficiency over the last decades. The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) suggested the introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by Member States (Economidou et al., 2020), a rationale followed by France and the Netherlands for certain segments of the housing stock. Currently, policy-makers are debating on whether the EPBD’s recast (COM/2021/802) should incorporate MEPS and make decarbonisation an obligation for SHOs across the EU. On the other hand, legislation on green finance aims to produce incentives and oversight over investments in energy efficient renovation and new build, mobilising the private sector to cater to green projects (Renovation Wave (COM(2020) 662)).

A.Fernandez. ESR12

Read more

->

WikiHouse: South Yorkshire Housing Association

Created on 16-10-2024

South Yorkshire Housing Association manages 6,000 homes to provide social and affordable rent housing for over 10,000 residents (SYHA, n.d.). The housing association is helping to lead the way in less conventional construction methods, utilising industrialised construction to deliver a portion of its homes. As a founding member of the Off Site Homes Alliance (OSHA, n.d.), SYHA is also part a framework and network of registered housing providers, local authorities, contractors, and strategic partners, dedicated to delivering high-quality, affordable housing produced using both 2D panelised and 3D volumetric approaches.

The two semi-detached WikiHouses, with an approximate floor area of 70m², are situated in Sheffield, close to the city centre. They were delivered in collaboration with product design providers Open Systems Lab, architects Architecture 00, engineers Momentum, manufacturers Chop Shop, and assembly and installation were carried out by Castle Building Services supported by Mascot Management. The project is not only exemplary in reducing embodied energy in housing but also proves to be energy efficient, having earned runner-up in the Ashden Awards for Energy Innovation.

Design

WikiHouse aims to democratise housing with the creation of standardised and open-source designs incorporating industrialised construction, based on foundational principles such interoperability and a lean approach inspired by the Toyota Production System (WikiHouse, n.d.-a). WikiHouse provided SYHA with a “jigsaw of pieces” in the form of panelised components designed to be assembled around a framing system. The system was made from simple plywood construction, with no need for steel due to the proposed low building height. Timber is not only ideal for buildability and deconstruct-ability as a lightweight material, but it also possesses carbon sequestering properties. It should be noted the open-source product can be limiting for some adopters of WikiHouse as additional design, construction and installation services are not included. SYHA therefore needed to fill the gap between the product and delivery to their end-users.

Manufacturing

WikiHouse products lend themselves to self-build construction or utilisation of ‘micro’ factories. SYHA’s pilot used localised construction to manufacture the plywood frame using digital files, cut by CNC machining company ‘Chop Shop’, located just 1 mile from the site (Plowden, 2020). Cutting the pieces was a fast and efficient process, which was designed to minimise material waste. Chop Shop also assisted by storing the building parts until the site was ready for assembly due to the lack of on-site storage space. WikiHouse seems to be well suited to manufacture by a distributed network of small manufacturers. However, according to SYHA, there is potential for scalability with larger housing association schemes in future. In addition, the production strategy is ideal to unlock small, tricky sites within the housing association’s portfolio, facilitating the production of high-quality housing with high circularity potential.

Transport and assembly

The dimensions of the timber frames were small enough to be delivered to site using a transit van rather than a larger lorry, which proved to be more manageable and cost effective. Once on site, the prefabricated building parts were assembled “like a jigsaw” using a step-by-step manual, although SYHA felt the instructions could be enhanced in the future to improve delivery by a range of stakeholders (Plowden, 2020).

The project programme was much shorter compared to a traditional build, the first home was manufactured and assembled in under a month. This process was even faster for the second home due to the experience gained from the first home, highlighting potential to improve efficiency for larger schemes in the future. As prefabrication and assembly are still unconventional, the transition between these processes may present additional complexity for the stakeholders involved compared to a traditional build.

In the case of SYHA’s WikiHouse, Miranda found “the manufacturer saw its job as providing the cut pieces for the installer to install, they didn't appreciate that they were part of a manufacturing process with the installer”. She went on to highlight that manufacturers and installers are typically separate parties in the UK, with installers often being main contractors who aren’t used to off-site methods. The team also had to overcome issues with unexpected ground conditions which hadn’t been included within the original site survey, though this was unrelated to the construction system used.

Building performance

SYHA’s WikiHouse homes have so far proven to be warm and energy efficient, resulting in low energy bills for residents, owing to the high-level of insulation within the plywood structure and panelling. The building strategy ensures easy maintenance and access during the use phase without disturbing residents. This was achieved by incorporating exterior services coupled with dry construction techniques. As a result of their involvement in the whole process, SYHA is able to effectively manage disassembly for future maintenance and potential adaptations, as their Home Maintenance Team were able to observe how the WikiHouses were assembled.

Legal

Providing the design and detailing are correctly implemented, meeting UK building regulations is not an issue with the WikiHouse system, which claims its products will exceed the requirements of UK building regulations (WikiHouse, n.d.-b). However, it proved more difficult to obtain the building warranty for the SYHA pilot. All new products need to be warranted, which requires warranters to inspect the whole building process to guarantee the necessary requirements are met.

SYHA’s WikiHouse utilised the Buildoffsite Property Assurance Scheme (BOPAS) (n.d.), which is a specialist warranty provider for buildings using industrialised construction, referred to as Modern Method of Construction (MMC) in the UK. Homes with BOPAS accreditation are readily mortgageable for a minimum of 60 years.

Financial

Using an off-site approach can be financially advantageous, as more time is invested upfront to plan, design, and manufacture. This shortens the time spent on-site and therefore reduces preliminary costs for the operation of the construction site. Although the project benefitted from a shortened timeline due to the industrialised approach, the WikiHouse system ultimately proved to be more expensive than a traditional build.

According to Miranda, the cost of the completed homes was approximately 33% higher than a traditional build but she estimates if they were to build using WikiHouse again - taking on-board lessons learnt - the premium would reduce to 12% (Plowden, 2020). However, there is hope for the WikiHouse system to become a more financially competitive alternative to traditional build in the future. For this to happen, Miranda suggests improving efficiency of the assembly process, particularly with faster utility connections. Additional financial viability could also be achieved if the system were to be applied to larger sites. In regard to a life cycle costing approach, Miranda believes it is too early for SYHA to say whether the WikiHouse pilot will prove to be cheaper than a traditional build in the long-term.

A.Davis. ESR1

Read more

->

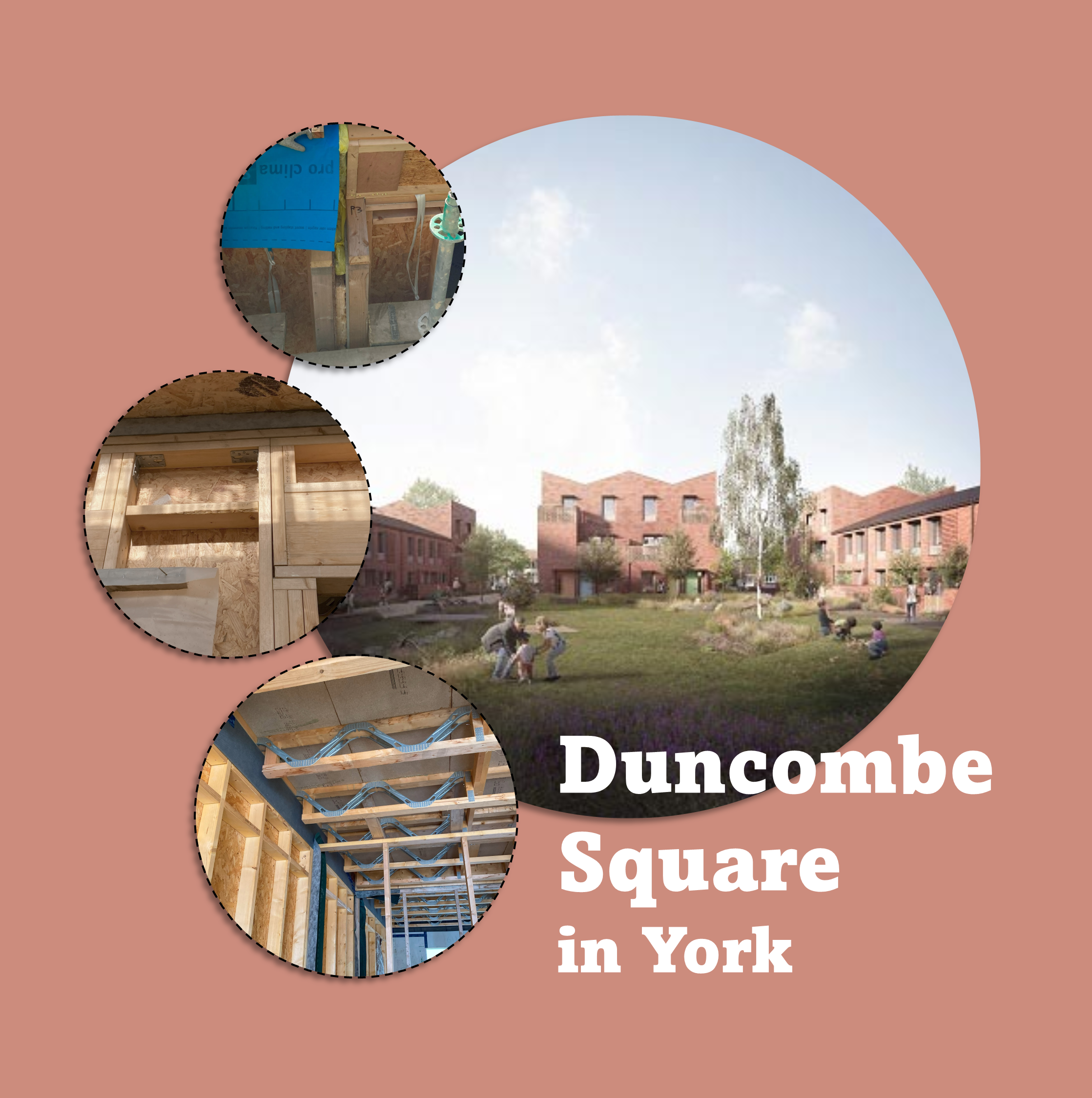

York's Duncombe Square Housing: Towards Affordability, Sustainability, and Healthier Living

Created on 15-11-2024

Strengthening Construction Quality and Knowledge Sharing

The City of York's procurement strategy for the Duncombe Square project, as well as other housing sites across the city, focused on two key objectives: ensuring high-quality construction and facilitating knowledge exchange about sustainable building practices. These objectives exemplify the council's commitment to its housing delivery programme.

To achieve housing quality, the council engaged a multidisciplinary design team led by the esteemed architect Mikhail Riches, known for his work on Norwich Goldsmith Street and association with the Passivhaus Trust. This team was supported by RICS-accredited project managers, clerks of work, and valuers to uphold stringent standards.

The project used two complementary approaches to improve the construction and delivery of large-scale Passivhaus projects in the UK. The first approach involved training to advance sustainable construction skills for existing staff, new hires, and students aged 14 to 19, led by the main contractor, Caddick Construction (Passivhaus Trust, 2022). The second approach is sharing knowledge with a broader audience by organising multiple tours during the different construction phases. These tours were designed for developers, architects, researchers, and housing professionals. They showcased Duncombe Square as an open case study, allowing industry peers to learn from and engage directly with project and site managers, reinforcing the project's role as a model for York’s Housing Delivery Programme.

Duncombe Square Housing Design

The design principles of the Duncombe Square project aim to integrate functionality and encourage healthy and sustainable lifestyles. The principles embody the essence of Passivhaus design while ensuring aesthetic appeal. It features low-rise, high-density terraced housing to optimise land use and foster a sense of community. The terraces are strategically positioned close together to maximise solar gain during the winter hours of sunlight, ensuring compliance with the rigorous Passivhaus standards while accommodating a maximum number of residences. The design ensures that each home benefits from natural light and heat while aligning with the Passivhaus energy efficiency and ventilation principles.

The facade design and colour scheme connect with the local architectural identity of traditional Victorian terraces, with a modern twist that cares for indoor environmental quality. It features high ceilings, thick insulated walls, and a fully airtight construction. The design incorporates traditional materials such as brick, enhanced by modern touches of render and timber shingles that blend harmoniously with the local surroundings.

The site plan design reflects a neighbourhood concept that extends beyond the energy-efficient and modern appearance of the houses. Duncombe is designed as a child-friendly neighbourhood, prioritising walking and cycling with dedicated cycle parking for each home. Vehicle parking and circulation are situated along the site's perimeter, ensuring paths are exclusively for pedestrians and play areas. Additionally, shared 'ginnels' provide bike access, enhancing mobility and creating safe play areas for children. This emphasis on pedestrian access enhances community interaction and outdoor activities. The thoughtful landscaping incorporates generous green open spaces at the development's core, complemented by communal growing beds and private planters. These features are intended to be aesthetically pleasing while also encouraging community engagement.

A Construction Adventure

For the main contractor, Caddick Construction, this project represents a distinctive adventure - from procurement to construction to Passivhaus standards - that deviates from traditional British construction practices. Recent UK housing developments often employ "Design and Build" contracts, where the contractor assumes primary responsibility for designing and constructing the project. However, the architects led the design process in this case, necessitating frequent collaborative meetings to discuss detailed execution plans.

During a site visit to the project site in York in September 2023, the contractor’s site manager explained the challenges of constructing and applying Passivhaus standards on a large scale. Unlike traditional construction, Passivhaus demands meticulous attention to detail to ensure robust airtightness of the building envelope. Moreover, building to these standards involves sending progress images to a Passivhaus certifier, who verifies that each construction step meets the rigorous criteria before approving further progress.

The chosen construction method for this project is off-site timber frame construction combined with brick and roughcast render. Prefabricated timber frames mitigate risks for contractors and expedite the construction process. The homes' superstructure employs timber frame technology, ensuring durability and longevity.

A key priority in the construction process is preventing heat loss and moisture infiltration. This involves:

Envelope Insulation: Airtightness is crucial for minimising heat loss. Therefore, the façade installation included airtight boards, tapes, membranes, timber frame insulation, and triple-glazed windows. Indoor airtightness is tested at least four times throughout the construction process to guarantee that residents will live in an airtight house.

Foundation and Floor Insulation: Three layers of insulation between the floor finishing and foundation prevent heat loss, enhance thermal efficiency, and control moisture penetration, protecting against groundwater leakage.

Households’ Health and Wellbeing

Households' health and wellbeing are foundational pillars in the development of the Duncombe Square project. In addition to the robust energy efficiency benefits of Passivhaus standards, this initiative underscores high indoor air quality through Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery (MVHR) units, which improve air quality and help mitigate issues like dampness and mould in airtight houses. To improve outdoor air quality, the design strategically reduces car usage by fostering a pedestrian-friendly environment with expansive green pathways that purify air and encourage outdoor activities. Amenities such as bike sheds with electric charging points and communal "cargo bikes" are also included.

Central to the project is a vibrant communal green space that facilitates relaxation, play, and social interactions—vital for mental and physical health. The scheme enhances residents' wellbeing by ensuring proximity to local amenities, promoting a healthier, more active lifestyle without reliance on vehicles. Extensive pedestrian and cycling paths, alongside wheelchair-friendly features, highlight the project's commitment to inclusivity and a healthy living environment. The design harmoniously integrates with local architecture and includes public amenity spaces that prioritise safe, child-friendly areas and places for social gatherings, fostering a strong community spirit.

When compared with the framework for sustainable housing focusing on health and wellbeing developed by Prochorskaite et al., (2016), the Duncombe project excels in incorporating features such as energy efficiency, thermal comfort, indoor air quality, noise prevention, daylight availability, and moisture control. Moreover, it emphasises accessible, quality public green spaces, attractive external views, and facilities encouraging social interaction and environmentally sustainable behaviours. Its compact neighbourhood design, sustainable transportation solutions, proximity to amenities, consideration of environmentally friendly construction materials, and efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions perfectly encapsulate the framework's objectives for providing sustainable housing focused on health and wellbeing.

Affordability

From a housing provider's perspective, the delivery team faced challenges in achieving a net-zero and Passivhaus standard that is affordable and scalable for large housing developments. For instance, construction costs are subject to pricing risks as contractors raise their prices amid market uncertainties, thereby increasing overall project expenses. Integrating Passivhaus principles is believed to have helped control these costs by simplifying building forms and reducing unnecessary complexities.

Residents' housing affordability is expected to be positively influenced by three key factors: tenure distribution, adherence to Passivhaus standards, and the development's central location. The tenure distribution includes 20% of units for social rent and 40% for shared ownership, offering affordable options for both renters and prospective homeowners. Passivhaus standards further reduce costs by lowering energy consumption through features like PV panels and energy-efficient air-source heat pumps, earning the development an A rating for energy performance and cutting utility bills for residents. Additionally, the central location decreases mobility-related expenses, with easy access to local amenities reducing the need for car use. Together, these factors help promote a sustainable lifestyle and lower overall living costs for residents.

Sustainability: Environmental, Social, and Economic Lens

Environmental sustainability involves two key aspects: (1) reducing resource consumption and (2) minimising emissions during use (Andersen et al., 2020). Duncombe Square's initiatives to reduce resource consumption include:

The dwelling's superstructure utilises low-carbon materials, such as FSC (Forest Steward Council) certified timber framing, which ensures it is sourced from sustainable forestry.

Using recycled newspaper for insulation to minimise environmental impact.

Monitoring the embodied energy of construction materials, including accounting for the energy used in their extraction, production, and transportation.

Sourcing 70% of subcontractors and supplies within 30 miles of the site, as per Passivhaus Trust guidelines, to reduce emissions from long-distance transportation.

To minimise environmental impact during use, the project incorporates:

Air-source heat pumps for heating and solar PV panels on roofs, enabling net-zero carbon energy usage.

Water butts for collecting rainwater for gardening purposes.

Permeable surfaces, rain gardens, and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) to reduce surface runoff in public areas.

Economic sustainability is at the forefront of providing affordable, energy-efficient dwellings that do not impose long-term financial burdens on residents. The project offers affordable dwellings in terms of housing costs, non-housing costs, and housing quality. It also contributes to the broader economy by promoting sustainable building practices and creating future jobs through on-site training programmes. Caddick Construction prioritises the local sourcing of subcontractors and suppliers within 30 miles of the site, thereby reducing transportation costs and supporting the local economy.

Social sustainability is integral to the project, featuring designs that promote community interaction and provide safe, accessible outdoor spaces. The development includes communal green spaces, such as plant-growing areas and a central green space for natural play, enhancing residents' quality of life. Prioritising pedestrian pathways and extensive cycle storage encourages a shift towards sustainable transport options, reducing reliance on cars and promoting healthier, more active lifestyles.

A.Elghandour. ESR4

Read more

->