Tijn Croon

ESR11

Tijn Melle Croon embarked on his PhD journey at Delft University of Technology in 2021, focusing his research on the impact of energy spikes on housing affordability for disadvantaged households. Drawing on interdisciplinary methods from economics, geography, political science, and development studies, Tijn's work delves into how targeted policies can alleviate energy poverty at various governance levels. He has regularly collaborated with national and local governments, NGOs, planning agencies, and social housing providers across France, Belgium, the UK, and the Netherlands, engaging in professional publications with organisations like Housing Europe and the European Federation for Living. Tijn actively contributes to the European Network for Housing Research and has conducted reviews for journals such as Energy Research & Social Science and Housing Studies. His research on the utility of poverty gap indices in energy policy design and evaluation, co-authored with his Delft supervisors Professor Marja Elsinga and Dr. Joris Hoekstra as well as TNO supervisors Dr. Peter Mulder and Dr. Francesco Dalla Longa, has been published in the peer reviewed Q1 journal Energy Policy. During the 2023 Michaelmas term, Tijn visited Professor Minna Sunikka-Blank at Cambridge University, collaborating on a paper exploring the driving characteristics and health outcomes related to the prebound effect. This phenomenon involves households rationing their energy consumption in inefficient dwellings due to financial concerns. Before embarking on his doctoral studies, Tijn worked as a consultant at Springco Urban Analytics, a Rotterdam-based research and advisory firm specialising in urban development and housing. In 2020, Tijn earned his M.Sc. in Sustainable Cities from King's College London, receiving the Best Thesis Award in the Geocomputation and Spatial Analysis research group under the guidance of Dr. Jon Reades. During his master's programme, Tijn and his fellow students won the Bank of England's annual Technology Competition, where they developed an idea for digitising debt counselling. In London, he also gained experience as a trainee at the Siemens Centre of Competence for Cities. Prior to these endeavours, Tijn obtained his B.Sc. in Political Science and Public Policy and an M.Sc. in Political Economy from the University of Amsterdam.

September, 11, 2023

November, 22, 2022

September, 17, 2021

The Governance of the Just Transition:

Targeting Energy Poverty across Europe

Energy price volatility is expected to remain high due to geopolitical uncertainty and the ongoing shift towards low-carbon energy generation. However, the impact of price spikes varies across society, with households having lower incomes, limited savings, and less energy-efficient homes experiencing a disproportionate burden. Energy poverty, the inability to secure sufficient domestic energy services, can have deteriorating effects on livelihoods. Consequently, addressing energy poverty has become a critical focus in policymaking and research, particularly within the context of the European Green Deal. This PhD project delves into how European policymakers can effectively target vulnerable households at risk of energy poverty to ensure that the transition towards low-carbon housing is perceived as a 'just transition.' It seeks to contribute to our understanding of 'recognitional justice' in several ways. Firstly, it highlights the added value of poverty gap indices in assessing the intensity and inequality of deprivation stemming from energy poverty. Additionally, it examines various strategies employed by government and social housing providers in France, the UK, and the Netherlands to alleviate energy poverty. Finally, it develops a multilevel governance framework that identifies and discusses the roles and responsibilities of different actors in European energy poverty alleviation. This project uses a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods to provide a comprehensive overview of how recognitional justice can be integrated into policies across various levels of governance. Through these efforts, it aims to enhance the identification of energy poverty, improve the efficiency of alleviation policies, and bolster public accountability among the responsible stakeholders.

The Governance of Energy Poverty Alleviation:

Comparative Analyses of Targeted Policies and Strategies across Europe

Energy price volatility is likely to remain high due to geopolitical uncertainty and the transformative transition towards low-carbon generation. However, the consequences of price peaks are unevenly distributed across society as households with low incomes, little savings, and inefficient dwellings are disproportionately affected. Energy poverty – the inability to secure sufficient domestic energy services that allow for participation in society – can have deteriorating effects on their livelihoods. Therefore, energy poverty alleviation has become an important policy and research area, not least in the context of the ‘Renovation Wave’, the European transition towards low-carbon housing. This PhD project explores opportunities for European policymakers to target vulnerable households at risk of energy poverty so that the Renovation Wave is perceived as a ‘just transition’. It aims to contribute to an understanding of ‘recognitional justice’ in several ways. First, it explores the added value of the energy poverty gap in assessing the intensity and inequality of deprivation caused by energy poverty. Moreover, these dimensions are used to identify driving household, dwelling and spatial characteristics of energy poverty in the Netherlands. Subsequently, it suggests targeted interventions housing associations could implement to support those in need and assesses the target efficiency of state-level support policies in France, the UK, and the Netherlands. Finally, it develops a multilevel governance framework indicating and discussing the roles and responsibilities of actors in European energy poverty alleviation. The project uses a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods to provide a comprehensive overview of how recognitional justice can be integrated into policies across governance levels. By doing this, it aims to enhance identification of energy poverty, efficiency of alleviation policies and public accountability of actors responsible.

The Governance of a Just Housing Transition:

Targeting Disadvantaged Households within the European ‘Renovation Wave’

As residential energy consumption constitutes a significant share of Europe’s carbon emissions, the European Commission aims to establish a ‘Renovation Wave’ by incentivising energy efficiency measures and renewable energy sources while discouraging the usage of fossil fuels. However, even though it is generally accepted that this can lower housing expenditure in the long term, policymakers are becoming increasingly concerned about the short-term negative effects that retrofit costs and levies may have on the position of disadvantaged households. This research seeks to provide insight into the effects of sustainability incentives on their ability to afford housing and explores the embeddedness of ‘just transition’ principles within multilevel housing governance. The overarching principles of recognitional justice, procedural justice and distributional justice will be conceptually deepened and empirically assessed in different housing contexts. To that end, I first intend to determine specific vulnerabilities that arise in this transition by quantitatively assessing microdata. Identifying the characteristics of those households at risk could help to comprehend differences and subsequently design policies that accommodate specific needs. In the following phase I will focus on case studies at different levels of housing governance, looking at the application of just transition principles on different levels, but also evaluating how municipalities, housing associations and other local actors identify inequitable transition outcomes and incorporate fairness within their policies. Besides scientific publications, the project’s output will include policy recommendations with guidelines for housing governance actors to address vulnerabilities and deliver a just housing transition.

Collaboration transcending the secondment

Posted on 17-10-2023

Secondments

Read more ->

Summer in the City

Posted on 13-06-2023

Conferences

Read more ->

Thriving Through Crises

Posted on 22-11-2022

Secondments

Read more ->

Bridging research and practice during secondment at Clarion

Posted on 08-04-2022

Secondments

Read more ->

Lisbon as an all-round learning experience

Posted on 29-09-2021

Reflections

Read more ->

Greater than the sum of its parts

Posted on 21-07-2021

Workshops

Read more ->

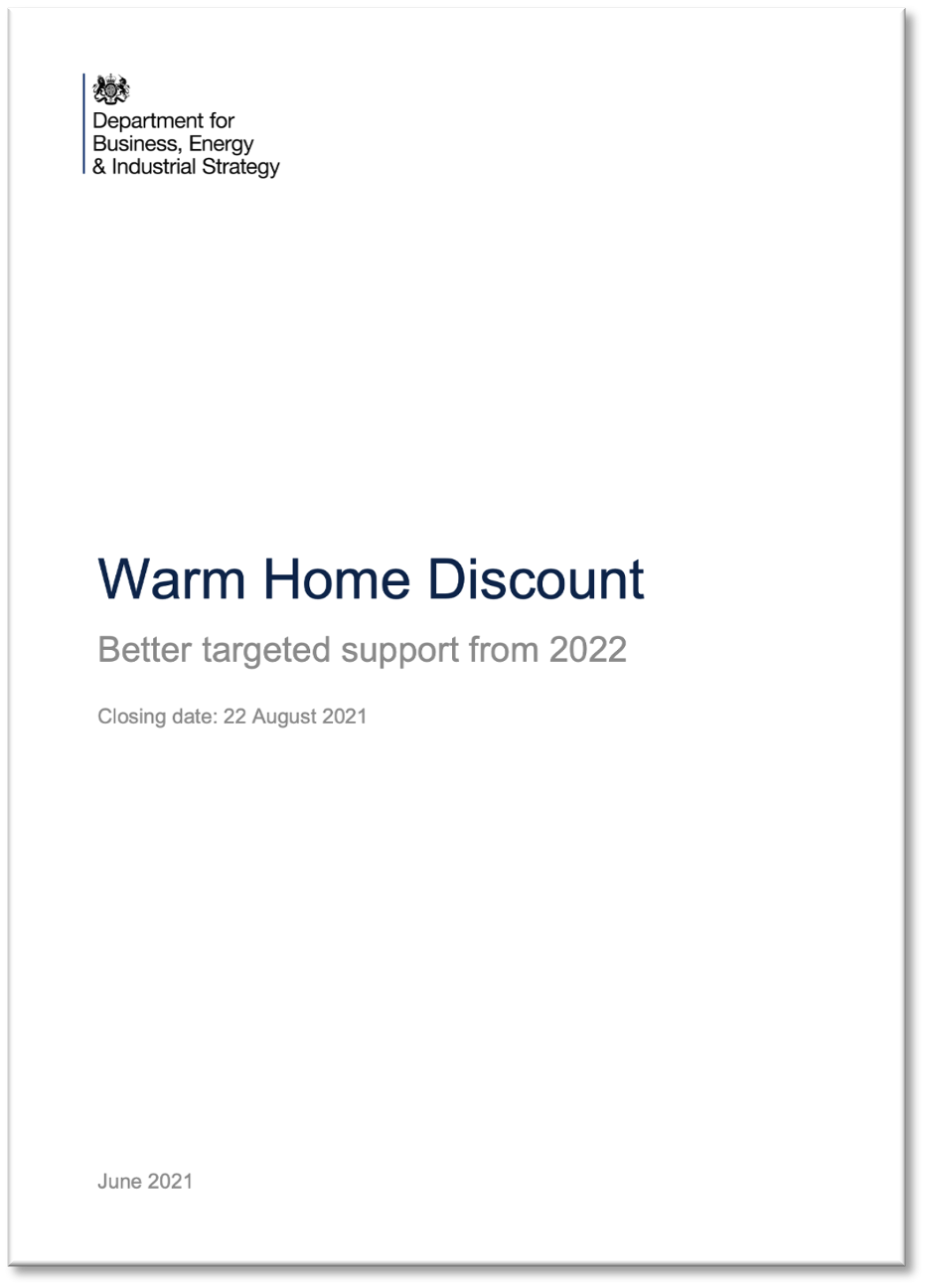

Targeting and Policy Efficiency: Exploring the Intended Reform of the Warm Home Discount

Created on 03-04-2023

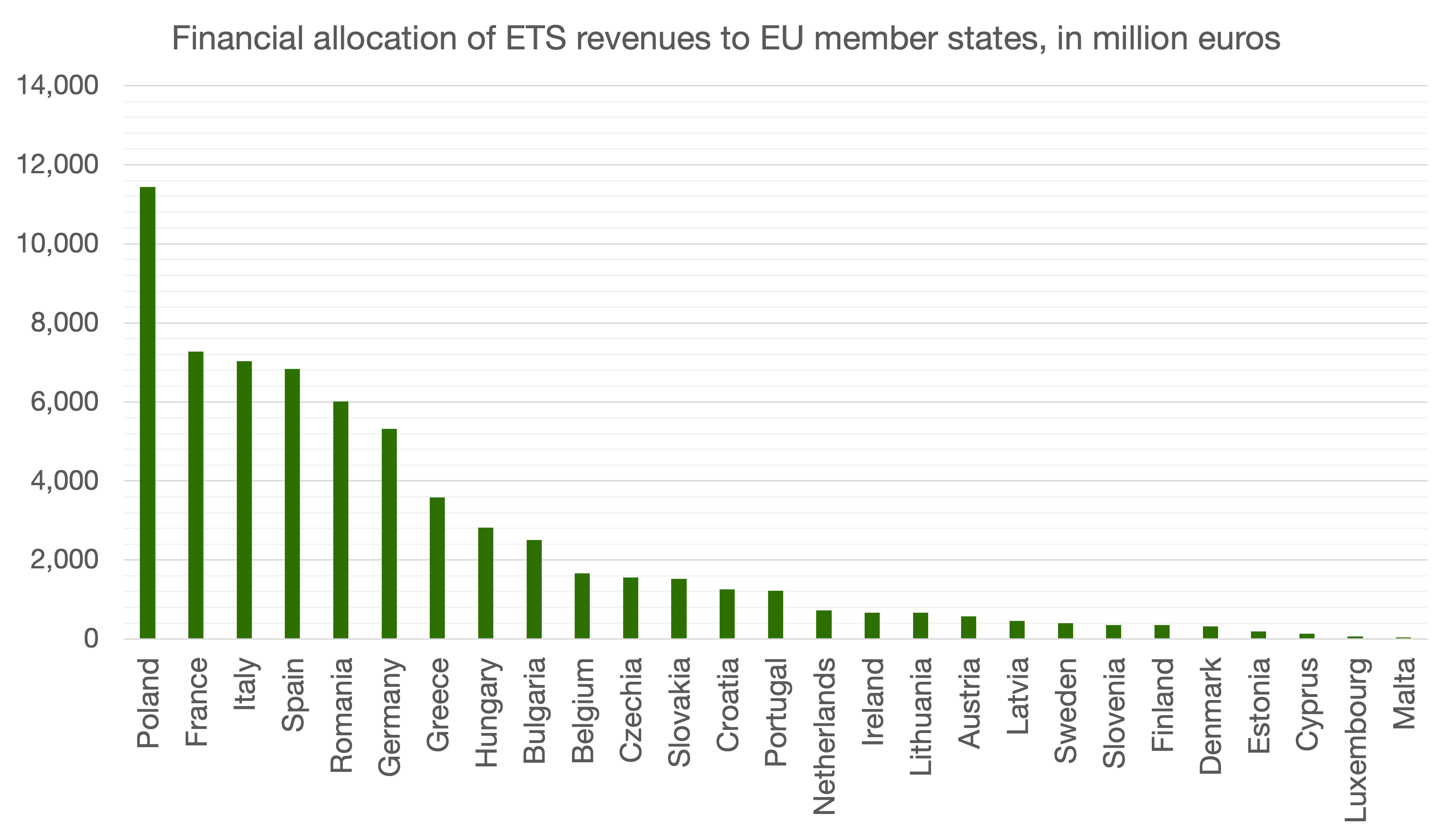

The Social Climate Fund: Materialising Just Transition Principles?

Created on 11-07-2023

A Combined Energy Efficiency and Levelling Up Scheme: the Dutch ‘Volkshuisvestingsfonds’

Created on 25-09-2024

Ecosocial Policy

Energy Poverty

Housing Governance

Just Transition

Prebound Effect

Sustainability

Targeted Universalism

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 20-06-2024

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 20-06-2024

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 21-07-2021

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-02-2024

Read more ->Croon, T.M., Hoekstra, J.S.C.M., Elsinga, M.G., Dalla Longa, F., & Mulder, P. (2022, June). Mind the gap: the use of poverty gap indices to quantify energy poverty in the netherlands [Conference Poster]. In 3rd International Conference on Energy Research & Social Science, Manchester, UK.

Posted on 14-02-2026

Conference

Read more ->