HOUSEFUL: Els Mestres, Sabadell

Created on 26-05-2023 | Updated on 12-03-2025

Bloc Els Mestres (The Teachers Block) is a social housing apartment block in Sabadell, Spain, that has recently undergone a deep energy retrofit (DER). Built in 1956 to house the teachers of the adjoining school, the building is one of four pilot projects in Spain and Austria to undergo retrofitting as part of the EU-funded project, HOUSEFUL (2018-2023). This initiative aimed to integrate circular solutions and services into the retrofit.

The school, the teachers’ residences, and the expansion of two housing estates were some of the first buildings to occupy the sparsely populated location of Sabadell Sud, which is near the city’s airport. By 1984, the expansion had reached Bloc Els Mestres which was no longer isolated between fields, but surrounded by residences to the North, West and East. By the year 2000, it was nestled in at all sides. By 2018, however, Bloc Els Mestres sat vacant, neglected, and in major need of renovation.

Today, the nine-story residential building, which occupies a triangular corner plot, boasts a distinctive façade of harmonious natural limestone, yellow render, terracotta brick, and glass panels, creating a warmth complemented by the Mediterranean sun. Two structurally sound wings fan out either side of the bright central stairwell, with two approximately 100m² four-bedroom apartments per floor—one in each wing (1st – 8th floor). The ground floor belongs to the community. The south-east building orientation allows light to stream through the square windows that punctuate the longest façades; slightly cantilevered balconies also benefit from this orientation. The apartment interiors are a simple white, giving tenants a wide scope to personalise and redecorate.

Architect(s)

In-house at Agència de l'Habitatge de Catalunya (AHC)

Location

Sabadell, Spain

Project (year)

2018 - 2021

Construction (year)

1956

Housing type

Social housing block, 4-bedroom apartments (converted from teachers’ apartments)

Urban context

suburb

Construction system

Solid brick and ceramic

Status

Building renovation

Description

Innovative Aspects of the Housing Design/Building:

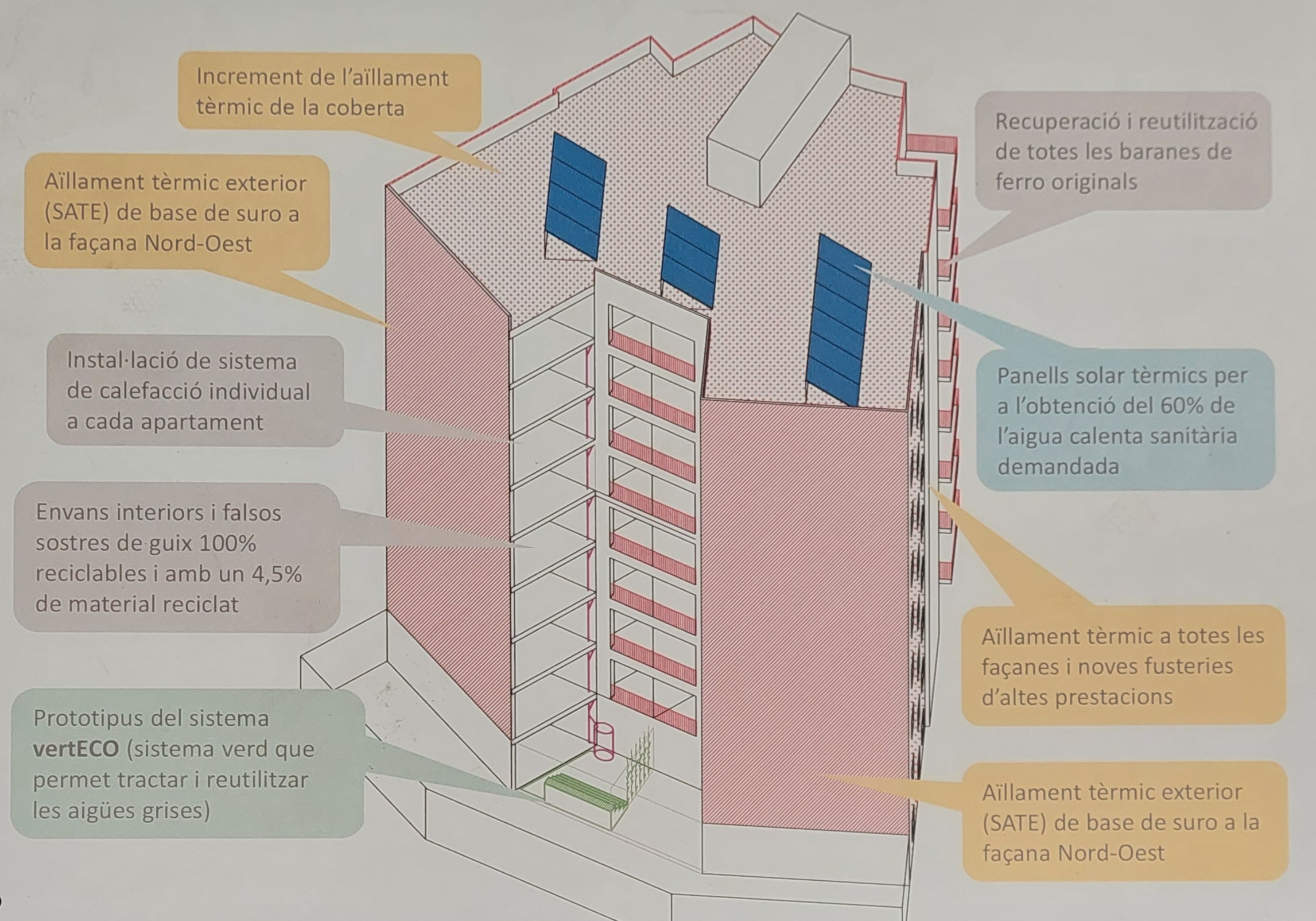

Bloc Els Mestres underwent a major retrofit as part of the EU-funded HOUSEFUL project, integrating innovative circular solutions and services. Tenants were involved through technical systems operation learning and feedback sessions. Tenant engagement methods included interviews and workshops focused on teaching residents how to engage with energy consumption and learning the energy consumption of home systems. As with typical DER, there were four main technical improvements to the building: (1) airtightness, (2) insulation, (3) smart systems, and (4) renewable energies. Circular solutions also incorporated into the retrofit to reduce waste include: (1) reusing the balcony balustrades after raising their height to meet building regulations, (2) recycled wall cladding product, and (3) greywater to be treated using the Nature Based Solution (NBS) of a green wall inside the courtyard.

Construction Characteristics, Materials, and Processes:

After the rehabilitation, the housing block has evolved into a resilient structure with two four-bedroom apartments per floor, spanning the 1st to the 8th floor. Its distinctive design encompasses an array of materials, from natural limestone and cork SATE for insulation to yellow render, terracotta brick, and unobstructed glass panels. With a strategic south-east orientation, the building optimizes natural light, thanks to square windows and cantilevered balconies. Inside, the apartments are designed in a clean, white palette, giving tenants the freedom to infuse their unique style and personal touch.

Energy Performance Characteristics:

Physical deep energy retrofit interventions included: cork external wall insulation; airtightness, fixing holes and fissures, double glazing, and other solutions to reduce thermal coefficient; mechanical ventilation; hydraulic balance valve with differential pressure measurement for the determination of the circulation flow, with insulation; and solar thermal panels, owned by the building owner, together increasing energy efficiency by approximately 50% compared to pre-retrofit. Tenants received technical training on how to use dwelling systems, potentially improving energy efficiency.

Involvement of Users and Other Stakeholders:

The rehabilitation process has involved collaborative decision-making among key stakeholders: LEITAT, non-profit organisation managing and researching sustainable technologies—project co-ordinators; AHC—Housing Agency of Catalonia and building owners; Sabadell Council; WE&B, organised co-creation activities and resident outreach; Housing Europe; members of the tenants’ association; Aiguasol, solar thermal energy; and ITEC, Catalan Institute of Construction and Technology—performed LCAs (life cycle analyses) to decide on cost-effectiveness of circular solutions.

The retrofit project encompassed low levels of tenant consultation and feedback sessions. The importance of managing conflicts that arise during tenant involvement in decision-making processes was recognised. A 'circularity agent' was proposed to teach tenants how to use complex technical systems, potentially fostering in-house expertise.

Relationship to Urban Environment:

Located in Sabadell Sud near the local airport, the block has undergone a significant transformation over the years. It has evolved from an isolated building, the once surrounding fields now transformed into a densely populated urban environment. Notably, it seamlessly integrates into this urban landscape, with a tonally harmonious façade that bathes the surroundings in a warm and visually appealing ambiance. The ground floor is dedicated to the community, fostering a strong connection to the local area and its residents. The nearby pedestrianized streets, adorned with benches, trees, and versatile playground equipment for all age groups, create a welcoming and inclusive atmosphere. This building plays a vital role as it provides accommodation exclusively for social housing residents, contributing to the rich social fabric of the urban community.

Alignment with project research areas

Design, planning, and building

- Existing building designed to retrofit with circular principles

- Novel NBS for greywater, through plants.

- Biowaste considered but removed.

Community participation

- Inclusive design for marginalised groups—keeping cost of bills low and neutral interiors

- Workshops and interviews with residents

- Decision-making with tenants’ association members on the board.

Policy and Financing

- The building is owned and managed by Agència de l’Habitatge de Catalunya (AHC).

- Partly financed by the HOUSEFUL Horizon 2020 project

- Part of the EU’s “Affordable housing initiative”.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

HOUSEFUL responds to the following Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

Goal 1 No Poverty: ensuring social housing that is affordable for all residents—four bedroom apartment costs 400-500 EUR per month.

Goal 6 Clean water and sanitation: greywater treated with NBS—a green wall inside the courtyard.

Goal 7 Affordable and clean energy: Passive and mechanical solutions to a reduction in energy costs and carbon output

Goal 9 Industry, innovation and infrastructure: Cork SATE (external wall insulation), circularity—reuse of existing balconies

Goal 12 Responsible consumption and production: Energy consumption results are pending, but the expected energy reduction is 50% compared with pre-retrofit.

References

Agència de l’Habitatge de Catalunya. (2022, October 5). Projecte HOUSEFUL.

Agència de l’Habitatge de Catalunya (AHC). (2018) PROJECTE DE REFORMA DE L'EDIFICI DE BLOC DELS MESTRES (I), Barcelona: AHC. Unpublished.

Houseful. (n.d.). HOUSEFUL: Els Mestres. Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://houseful.eu/demos/els-mestres/

Medina, B., Brummer, M., & Smith, D. (2019). D 3.1: Social engagement strategy for the co-creation of HOUSEFUL solutions as new services (version I). Barcelona: Houseful. Unpublished.

Related vocabulary

Energy Retrofit

Housing Retrofit

Social Housing

Sustainability

Techno-optimism

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 23-05-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 17-06-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Blogposts

Housing Europe Secondment: When Technical Retrofit Meets Social Value

Posted on 22-11-2024

Secondments

Read more ->

Retrofit and The Social Agenda

Posted on 08-05-2023

Secondments

Read more ->