York's Duncombe Square Housing: Towards Affordability, Sustainability, and Healthier Living

Created on 26-06-2024 | Updated on 15-11-2024

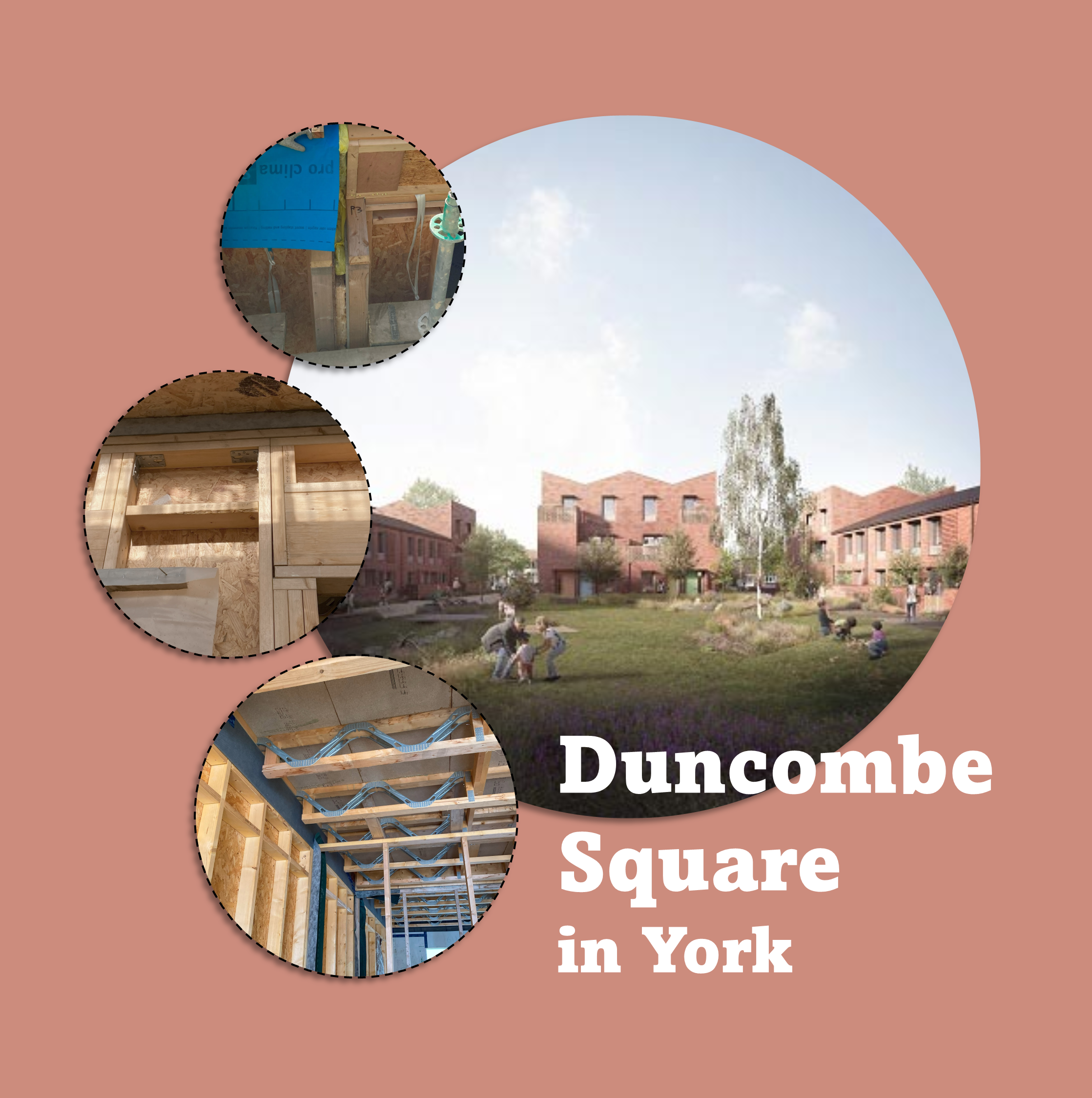

Duncombe Square, a housing project in the City of York, is a key part of the council's housing delivery programme initiated after the declaration of climate emergency in March 2019. Michael Jones, the head of housing delivery and asset management, notes that the programme addresses the high demand for homes, tackles social isolation, climate change, and supports community health.

According to the Passivhaus trust, Duncombe Square is Yorkshire's biggest affordable housing project. The residences were designed to promote healthy and low-carbon living. Providing warm and well-ventilated indoors is expected to lower risks of excess cold and mould accumulation. Those risks represent significant health hazards in British dwellings. Additionally, features like air-source heat pumps and PV panels are expected to reduce energy use and bills by approximately 70%, achieving zero-carbon in-use and affordable running costs for residents.

The project offers 60% of its 34 homes as affordable housing options, split between social rent and shared ownership. It includes a range of housing, from 1-bedroom flats to 4-bedroom family houses. The development also features well-designed outdoor spaces and a communal green area.

Duncombe Square, designed by Mikhail Riches, a Stirling Prize-winning architect, exemplifies the council's housing delivery programme. Additionally, community input via multiple consultations was vital in shaping the project brief. The project has garnered multiple accolades, including the Housing Design Awards and Planning Awards 2022, showcasing how modern design can enhance local architecture and community wellbeing. The council hopes this project will inspire other local councils and housing developers in the UK to create healthy, beautiful, and inclusive environments.

Architect(s)

Mikhail Riches

Location

York, UK

Project (year)

2020

Construction (year)

2022 - 2024

Housing type

Terraced housing

Urban context

City center

Construction system

Off-site timber frame construction

Status

Built

Description

Strengthening Construction Quality and Knowledge Sharing

The City of York's procurement strategy for the Duncombe Square project, as well as other housing sites across the city, focused on two key objectives: ensuring high-quality construction and facilitating knowledge exchange about sustainable building practices. These objectives exemplify the council's commitment to its housing delivery programme.

To achieve housing quality, the council engaged a multidisciplinary design team led by the esteemed architect Mikhail Riches, known for his work on Norwich Goldsmith Street and association with the Passivhaus Trust. This team was supported by RICS-accredited project managers, clerks of work, and valuers to uphold stringent standards.

The project used two complementary approaches to improve the construction and delivery of large-scale Passivhaus projects in the UK. The first approach involved training to advance sustainable construction skills for existing staff, new hires, and students aged 14 to 19, led by the main contractor, Caddick Construction (Passivhaus Trust, 2022). The second approach is sharing knowledge with a broader audience by organising multiple tours during the different construction phases. These tours were designed for developers, architects, researchers, and housing professionals. They showcased Duncombe Square as an open case study, allowing industry peers to learn from and engage directly with project and site managers, reinforcing the project's role as a model for York’s Housing Delivery Programme.

Duncombe Square Housing Design

The design principles of the Duncombe Square project aim to integrate functionality and encourage healthy and sustainable lifestyles. The principles embody the essence of Passivhaus design while ensuring aesthetic appeal. It features low-rise, high-density terraced housing to optimise land use and foster a sense of community. The terraces are strategically positioned close together to maximise solar gain during the winter hours of sunlight, ensuring compliance with the rigorous Passivhaus standards while accommodating a maximum number of residences. The design ensures that each home benefits from natural light and heat while aligning with the Passivhaus energy efficiency and ventilation principles.

The facade design and colour scheme connect with the local architectural identity of traditional Victorian terraces, with a modern twist that cares for indoor environmental quality. It features high ceilings, thick insulated walls, and a fully airtight construction. The design incorporates traditional materials such as brick, enhanced by modern touches of render and timber shingles that blend harmoniously with the local surroundings.

The site plan design reflects a neighbourhood concept that extends beyond the energy-efficient and modern appearance of the houses. Duncombe is designed as a child-friendly neighbourhood, prioritising walking and cycling with dedicated cycle parking for each home. Vehicle parking and circulation are situated along the site's perimeter, ensuring paths are exclusively for pedestrians and play areas. Additionally, shared 'ginnels' provide bike access, enhancing mobility and creating safe play areas for children. This emphasis on pedestrian access enhances community interaction and outdoor activities. The thoughtful landscaping incorporates generous green open spaces at the development's core, complemented by communal growing beds and private planters. These features are intended to be aesthetically pleasing while also encouraging community engagement.

A Construction Adventure

For the main contractor, Caddick Construction, this project represents a distinctive adventure - from procurement to construction to Passivhaus standards - that deviates from traditional British construction practices. Recent UK housing developments often employ "Design and Build" contracts, where the contractor assumes primary responsibility for designing and constructing the project. However, the architects led the design process in this case, necessitating frequent collaborative meetings to discuss detailed execution plans.

During a site visit to the project site in York in September 2023, the contractor’s site manager explained the challenges of constructing and applying Passivhaus standards on a large scale. Unlike traditional construction, Passivhaus demands meticulous attention to detail to ensure robust airtightness of the building envelope. Moreover, building to these standards involves sending progress images to a Passivhaus certifier, who verifies that each construction step meets the rigorous criteria before approving further progress.

The chosen construction method for this project is off-site timber frame construction combined with brick and roughcast render. Prefabricated timber frames mitigate risks for contractors and expedite the construction process. The homes' superstructure employs timber frame technology, ensuring durability and longevity.

A key priority in the construction process is preventing heat loss and moisture infiltration. This involves:

- Envelope Insulation: Airtightness is crucial for minimising heat loss. Therefore, the façade installation included airtight boards, tapes, membranes, timber frame insulation, and triple-glazed windows. Indoor airtightness is tested at least four times throughout the construction process to guarantee that residents will live in an airtight house.

- Foundation and Floor Insulation: Three layers of insulation between the floor finishing and foundation prevent heat loss, enhance thermal efficiency, and control moisture penetration, protecting against groundwater leakage.

Households’ Health and Wellbeing

Households' health and wellbeing are foundational pillars in the development of the Duncombe Square project. In addition to the robust energy efficiency benefits of Passivhaus standards, this initiative underscores high indoor air quality through Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery (MVHR) units, which improve air quality and help mitigate issues like dampness and mould in airtight houses. To improve outdoor air quality, the design strategically reduces car usage by fostering a pedestrian-friendly environment with expansive green pathways that purify air and encourage outdoor activities. Amenities such as bike sheds with electric charging points and communal "cargo bikes" are also included.

Central to the project is a vibrant communal green space that facilitates relaxation, play, and social interactions—vital for mental and physical health. The scheme enhances residents' wellbeing by ensuring proximity to local amenities, promoting a healthier, more active lifestyle without reliance on vehicles. Extensive pedestrian and cycling paths, alongside wheelchair-friendly features, highlight the project's commitment to inclusivity and a healthy living environment. The design harmoniously integrates with local architecture and includes public amenity spaces that prioritise safe, child-friendly areas and places for social gatherings, fostering a strong community spirit.

When compared with the framework for sustainable housing focusing on health and wellbeing developed by Prochorskaite et al., (2016), the Duncombe project excels in incorporating features such as energy efficiency, thermal comfort, indoor air quality, noise prevention, daylight availability, and moisture control. Moreover, it emphasises accessible, quality public green spaces, attractive external views, and facilities encouraging social interaction and environmentally sustainable behaviours. Its compact neighbourhood design, sustainable transportation solutions, proximity to amenities, consideration of environmentally friendly construction materials, and efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions perfectly encapsulate the framework's objectives for providing sustainable housing focused on health and wellbeing.

Affordability

From a housing provider's perspective, the delivery team faced challenges in achieving a net-zero and Passivhaus standard that is affordable and scalable for large housing developments. For instance, construction costs are subject to pricing risks as contractors raise their prices amid market uncertainties, thereby increasing overall project expenses. Integrating Passivhaus principles is believed to have helped control these costs by simplifying building forms and reducing unnecessary complexities.

Residents' housing affordability is expected to be positively influenced by three key factors: tenure distribution, adherence to Passivhaus standards, and the development's central location. The tenure distribution includes 20% of units for social rent and 40% for shared ownership, offering affordable options for both renters and prospective homeowners. Passivhaus standards further reduce costs by lowering energy consumption through features like PV panels and energy-efficient air-source heat pumps, earning the development an A rating for energy performance and cutting utility bills for residents. Additionally, the central location decreases mobility-related expenses, with easy access to local amenities reducing the need for car use. Together, these factors help promote a sustainable lifestyle and lower overall living costs for residents.

Sustainability: Environmental, Social, and Economic Lens

Environmental sustainability involves two key aspects: (1) reducing resource consumption and (2) minimising emissions during use (Andersen et al., 2020). Duncombe Square's initiatives to reduce resource consumption include:

- The dwelling's superstructure utilises low-carbon materials, such as FSC (Forest Steward Council) certified timber framing, which ensures it is sourced from sustainable forestry.

- Using recycled newspaper for insulation to minimise environmental impact.

- Monitoring the embodied energy of construction materials, including accounting for the energy used in their extraction, production, and transportation.

- Sourcing 70% of subcontractors and supplies within 30 miles of the site, as per Passivhaus Trust guidelines, to reduce emissions from long-distance transportation.

To minimise environmental impact during use, the project incorporates:

- Air-source heat pumps for heating and solar PV panels on roofs, enabling net-zero carbon energy usage.

- Water butts for collecting rainwater for gardening purposes.

- Permeable surfaces, rain gardens, and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) to reduce surface runoff in public areas.

Economic sustainability is at the forefront of providing affordable, energy-efficient dwellings that do not impose long-term financial burdens on residents. The project offers affordable dwellings in terms of housing costs, non-housing costs, and housing quality. It also contributes to the broader economy by promoting sustainable building practices and creating future jobs through on-site training programmes. Caddick Construction prioritises the local sourcing of subcontractors and suppliers within 30 miles of the site, thereby reducing transportation costs and supporting the local economy.

Social sustainability is integral to the project, featuring designs that promote community interaction and provide safe, accessible outdoor spaces. The development includes communal green spaces, such as plant-growing areas and a central green space for natural play, enhancing residents' quality of life. Prioritising pedestrian pathways and extensive cycle storage encourages a shift towards sustainable transport options, reducing reliance on cars and promoting healthier, more active lifestyles.

Alignment with project research areas

Design, Planning and Building

This project serves as an exemplary integration of design, planning, and construction, with a focus on promoting the health and wellbeing of future residents as well as environmental sustainability through conscious, sustainable approaches:

Design: The design prioritises the health and wellbeing of households by incorporating Passivhaus principles and selecting sustainable materials with aesthetic appeal. Blending with the local architectural identity, it features low-rise, high-density terraced housing that incorporates traditional materials like brick alongside modern touches such as render and timber shingles.

Construction: The construction deviates from the typical Design and Build procurement approach, with the architect leading the design process and working closely with the contractor throughout execution. The focus is on airtightness, energy efficiency, and indoor air quality to meet Passivhaus standards, requiring precise installations and multiple tests. Additionally, off-site timber frame construction is used for the main building structure as a sustainable choice.

Planning: The site’s planning emphasises a child-friendly, pedestrian-focused neighbourhood, prioritising walking and cycling. Vehicle parking is placed along the perimeter, with dedicated cycle parking for each home. The development’s core features generous green spaces, communal growing plots, and private planters to encourage outdoor activities, community interaction, and engagement.

Community participation

The project demonstrates a commitment to community participation articulated in various forms:

Consultation on design brief: The project's development involved consultations with local residents and Clifton Green Primary School students to ensure integration with the existing community. Their active participation through drop-in events, workshops, and an online consultation during the COVID-19 lockdown in Autumn 2020. These consultations aligned the project’s design brief with community needs and expectations.

Living with others: The development design aims to foster strong community ties and sustainable living. Though not yet occupied, the design aimed to create a neighbourly atmosphere by encouraging reduced car use and prioritising cycling infrastructure, including dedicated paths and cycle parking. Features like communal food-growing areas, planting spaces, and child-friendly zones are intended to encourage social interaction and support sustainable lifestyles once residents move in.

Contribution to a broader community: The project is committed to developing sustainable construction skills (Passivhaus Trust, 2022) and knowledge-sharing (Passivhaus Trust, 2023). Caddick Construction provides staff, new hires, and students with sustainable construction training. The City of York Council collaborates with local institutions like York College and Job Centre Plus to support broader workforce development and build "Green Skills" within the supply chain. Knowledge-sharing activities involve site visits, presenting the project as an open case study that allows different stakeholders to engage with ongoing development that adopts sustainable construction techniques and Passivhaus standards. These efforts aim to create job opportunities and inspire other stakeholders to replicate similar projects across the UK, benefiting people and the environment beyond this development.

Finance and policy

The Duncombe Square project is financially structured through a collaboration with Homes England and local funding sources. Homes England's support has enabled additional funding through the Affordable Homes Programme, complementing other financial contributions, which include right-to-buy receipts and market sales. To ensure economic sustainability, 60% of the homes are allocated for affordable options, comprising 20% for social rent and 40% for shared ownership—exceeding local planning requirements—while the remaining 40% are sold on the open market. This market revenue helps subsidise the affordable housing component.

The project's total cost is 14 million GBP, with expenditures broken down as follows: land costs 2 million GBP, construction costs 10 million GBP, and additional on-costs amount to 2 million GBP. This financial model allows the City of York Council to maintain a self-sustaining development strategy despite limited government funding, ensuring the project remains feasible and continues to provide affordable housing options.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

The Duncombe Square development is aligned with the following Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

GOAL 3: Good Health and Well-being - The project’s design and construction prioritize the health and well-being of residents, reflecting a genuine commitment to improving their quality of life.

GOAL 4: Quality Education - By encouraging education on sustainable construction, the council supports the development of practical skills for future generations. Additionally, using Duncombe Square as an open case study through site visits, offers housing stakeholders an educational opportunity to explore and ask questions.

GOAL 7: Affordable and Clean Energy - The project is expected to achieve both by adhering to stringent Passivhaus standards, which ensure energy efficiency and cost savings.

GOAL 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure – The project showcases innovation by overcoming challenges in constructing 34 homes to Passivhaus standards. It aims to encourage infrastructure development that supplies the advanced systems required for this standard on a larger scale and for the long term in the UK.

GOAL 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities – Duncombe Square serves as an example of sustainable housing, from the choice of construction materials to landscape design, fostering sustainable, healthy and active lifestyles that engage the community.

GOAL 12: Responsible Consumption and Production – This goal is demonstrated through the use of recycled insulation materials, air-source heat pumps, solar PV panels, and rainwater collection systems for gardening.

GOAL 13: Climate Action – The project supports climate action by promoting low-carbon living through features like air-source heat pumps, solar PV panels, and timber-based structures, all of which help reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

References

Andersen, C. E., Ohms, P., Rasmussen, F. N., Birgisdóttir, H., Birkved, M., Hauschild, M., & Ryberg, M. (2020). Assessment of absolute environmental sustainability in the built environment. Building and Environment, 171(October 2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106633

City of York Council. (n.d.). Housing delivery programme. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://www.york.gov.uk/housing/housing-delivery-programme-1/3

Housing Design Awards. (n.d.). Duncombe Barracks and Burnholme. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://hdawards.org/scheme/duncombe-barracks-and-burnholme/

Prochorskaite, A., Couch, C., Malys, N., & Maliene, V. (2016). Housing Stakeholder Preferences for the “Soft” Features of Sustainable and Healthy Housing Design in the UK. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010111

Passivhaus Trust. (2022, August 4). City of York Council housing delivery programme. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from https://www.passivhaustrust.org.uk/news/detail/?nId=1120

Passivhaus Trust. (2023, August 18). Site visit: Duncombe Square Passivhaus Tour. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://passivhaustrust.org.uk/event_detail.php?eId=1200

Shape Homes York. (n.d.). Duncombe Barracks and Burnholme. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://www.shapehomesyork.com/development/2

Jones, M. (2022, April 22). Green homes aim to set international example. Property Journal. Retrieved May 28, 2024, from https://ww3.rics.org/uk/en/journals/property-journal/green-homes-aim-to-set-international-example.html

More Reading

Wainwright, O. (2020, October 4). Everest zero carbon: Inside York's green home revolution. *The Guardian*. Retrieved May 20, 2024, from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/oct/04/everest-zero-carbon-inside-yorks-green-home-revolution

Related vocabulary

Financial Wellbeing

Housing Affordability

Measuring Housing Affordability

Participatory Approaches

Social Sustainability

Sustainability

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 17-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-06-2022

Read more ->