Just Transition

Area: Policy and financing

Justice theory is as old as philosophical thought itself, but the contemporary debate often departs from the Rawlsian understanding of justice (Velasquez, Andre, Shanks, & Meyer, 1990). Rawls (1971) argued that societal harmony depends on the extent to which community members believe their political institutions treat them justly. His First Principle of ‘justice as fairness’ relates to equal provision of ‘basic liberties’ to the population. His Second Principle, later referred to as the ‘Difference Principle’, comprises unequal distribution of social and economic goods to the extent that it benefits “the least advantaged” (Rawls, 1971, p. 266).1[1] As this notion added an egalitarian perspective to Rawlsian justice theory, it turned out to be the most controversial element of his work (Estlund, 1996).

The idea of a ‘just transition’ was built on these foundations by McCauley and Heffron (2018), who developed an integrated framework overarching the ‘environmental justice’, ‘climate justice’ and ‘energy justice’ scholarships. The term was first used by trade unions warning for mass redundancies in carbon-intensive industries due to climate policies (Hennebert & Bourque, 2011), but has acquired numerous interpretations since. This is because the major transition of the 21st century, the shift towards a low-carbon society, will be accompanied by large disturbances in the existing social order. In this context, a just transition would ensure equity and justice for those whose livelihoods are most affected (Newell & Mulvaney, 2013). A just transition implies that the ‘least advantaged’ in society are seen, heard, and compensated, which corresponds with three key dimensions conceptualised by Schlosberg (2004): distributive, recognitional, and procedural justice.

Distributive justice corresponds with Rawls’ Difference Principle and comprehends the just allocation of burdens and benefits among stakeholders, ranging from money to risks to capabilities. Recognitional justice is both a condition of justice, as distributive injustice mainly emanates from lacking recognition of different starting positions, as well as a stand-alone component of justice, which includes culturally or symbolically rooted patterns of inequity in representation, interpretation, and communication (Young, 1990). Fraser (1997) stressed the distinction between three forms: cultural domination, nonrecognition (or ‘invisibility’), and disrespect (or ‘stereotyping’). Procedural justice emphasises the importance of engaging various stakeholders – especially the ‘least advantaged’ – in governance, as diversity of perspectives allows for equitable policymaking. Three elements are at the core of this procedural justice (Gillard, Snell, & Bevan, 2017): easily accessible processes, transparent decision-making with possibilities to contest and complete impartiality.

A critique of the just transition discourse is that it preserves an underlying capitalist structure of power imbalance and inequality. Bouzarovski (2022) points to the extensive top- down nature of retrofit programmes such as the Green New Deal, and notes that this may collide with bottom-up forms of housing repair and material intervention. A consensus on the just transition mechanism without debate on its implementation could perpetuate the status quo, and thus neglect ‘diverse knowledges’, ‘plural pathways’ and the ‘inherently political nature of transformations’ (Scoones et al., 2020). However, as Healy and Barry (2017) note, understanding how just transition principles work in practice could benefit the act of ‘equality- proofing’ and ‘democracy-proofing’ decarbonisation decisions.

Essentially, an ‘unjust transition’ in the context of affordable and sustainable housing would refer to low-income households in poorly insulated housing without the means or the autonomy to substantially improve energy efficiency. If fossil fuel prices – either by market forces or regulatory incentives – go up, it aggravates their already difficult financial situation and could even lead to severe health problems (Santamouris et al., 2014). At the same time, grants for renovations and home improvements are poorly targeted and often end up in the hands of higher income ‘free-riding’ households, having regressive distributional impacts across Europe (Schleich, 2019). But even when the strive towards a just transition is omnipresent, practice will come with dilemmas. Von Platten, Mangold, and Mjörnell (2020) argue for instance that while prioritising energy efficiency improvements among low-income households is a commendable policy objective, putting them on ‘the frontline’ of retrofit experiments may also burden them with start-up problems and economic risks.

These challenges only accentuate that shaping a just transition is not an easy task. Therefore, both researchers and policymakers need to enhance their understanding of the social consequences that the transition towards low-carbon housing encompasses. Walker and Day (2012) applied Schlosberg’s dimensions to this context. They conclude that distributive injustice relates to inequality in terms of income, housing and pricing, recognitional justice to unidentified energy needs and vulnerabilities, and procedural injustice to inadequate access to policymaking. Ensuring that the European Renovation Wave is made into a just transition towards affordable and sustainable housing therefore requires an in-depth study into distributive, recognitional and procedural justice. Only then can those intertwining dimensions be addressed in policies.

[1] To illustrate his thesis, he introduces the ‘veil of ignorance’: what if we may redefine the social scheme, but without knowing our own place? Rawls believes that most people, whether from self-interest or not, would envision a society with political rights for all and limited economic and social inequality.

References

Bouzarovski, S. (2022). Just Transitions: A Political Ecology Critique. Antipode. doi:10.1111/anti.12823

Estlund, D. (1996). The Survival of Egalitarian Justice in John Rawls’s Political Liberalism. Journal of Political Philosophy, 4(1), 68-78.

Fraser, N. (1997). Justice interruptus. London: Routledge.

Gillard, R., Snell, C., & Bevan, M. (2017). Advancing an energy justice perspective of fuel poverty: Household vulnerability and domestic retrofit policy in the United Kingdom. Energy Research & Social Science, 29, 53-61. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.012

Healy, N., & Barry, J. (2017). Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: Fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition”. Energy Policy, 108, 451-459. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.06.014

Hennebert, M. A., & Bourque, R. (2011). The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC): Insights from the Second World Congress. Global Labour Journal, 2(2), 154-159.

McCauley, D., & Heffron, R. (2018). Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy, 119, 1-7. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

Newell, P., & Mulvaney, D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition’. The Geographical Journal, 179(2), 132-140. doi:10.1111/geoj.12008

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Santamouris, M., Alevizos, S. M., Aslanoglou, L., Mantzios, D., Milonas, P., Sarelli, I., . . . Paravantis, J. A. (2014). Freezing the poor—Indoor environmental quality in low and very low income households during the winter period in Athens. Energy and Buildings, 70, 61-70. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.11.074

Schleich, J. (2019). Energy efficient technology adoption in low-income households in the European Union – What is the evidence? Energy Policy, 125, 196-206. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.10.061

Schlosberg, D. (2004). Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements And Political Theories. Environmental Politics, 13(3), 517-540. doi:10.1080/0964401042000229025

Scoones, I., Stirling, A., Abrol, D., Atela, J., Charli-Joseph, L., Eakin, H., . . . Yang, L. (2020). Transformations to sustainability: combining structural, systemic and enabling approaches. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 42, 65-75. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.004

Velasquez, M., Andre, C., Shanks, T. S. J., & Meyer, M. J. (1990). Justice and fairness. Issues in Ethics, 3(2), 1-3.

Von Platten, J., Mangold, M., & Mjörnell, K. (2020). A matter of metrics? How analysing per capita energy use changes the face of energy efficient housing in Sweden and reveals injustices in the energy transition. Energy Research & Social Science, 70. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101807

Walker, G., & Day, R. (2012). Fuel poverty as injustice: Integrating distribution, recognition and procedure in the struggle for affordable warmth. Energy Policy, 49, 69-75. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.01.044

Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press.

Created on 03-06-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Related definitions

Housing Governance

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 16-02-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Indoor Thermal Comfort

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 20-09-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Window Guidance

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 24-04-2023 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Energy Poverty

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 17-10-2023 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Targeted Universalism

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-02-2024 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Deliberative Democracy

Area: Community participation

Created on 19-06-2024 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Ecosocial Policy

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 20-06-2024 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Financial Wellbeing

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024 | Update on 13-06-2025

Read more ->Homelessness

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 21-10-2024 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Related cases

Targeting and Policy Efficiency: Exploring the Intended Reform of the Warm Home Discount

Created on 03-04-2023

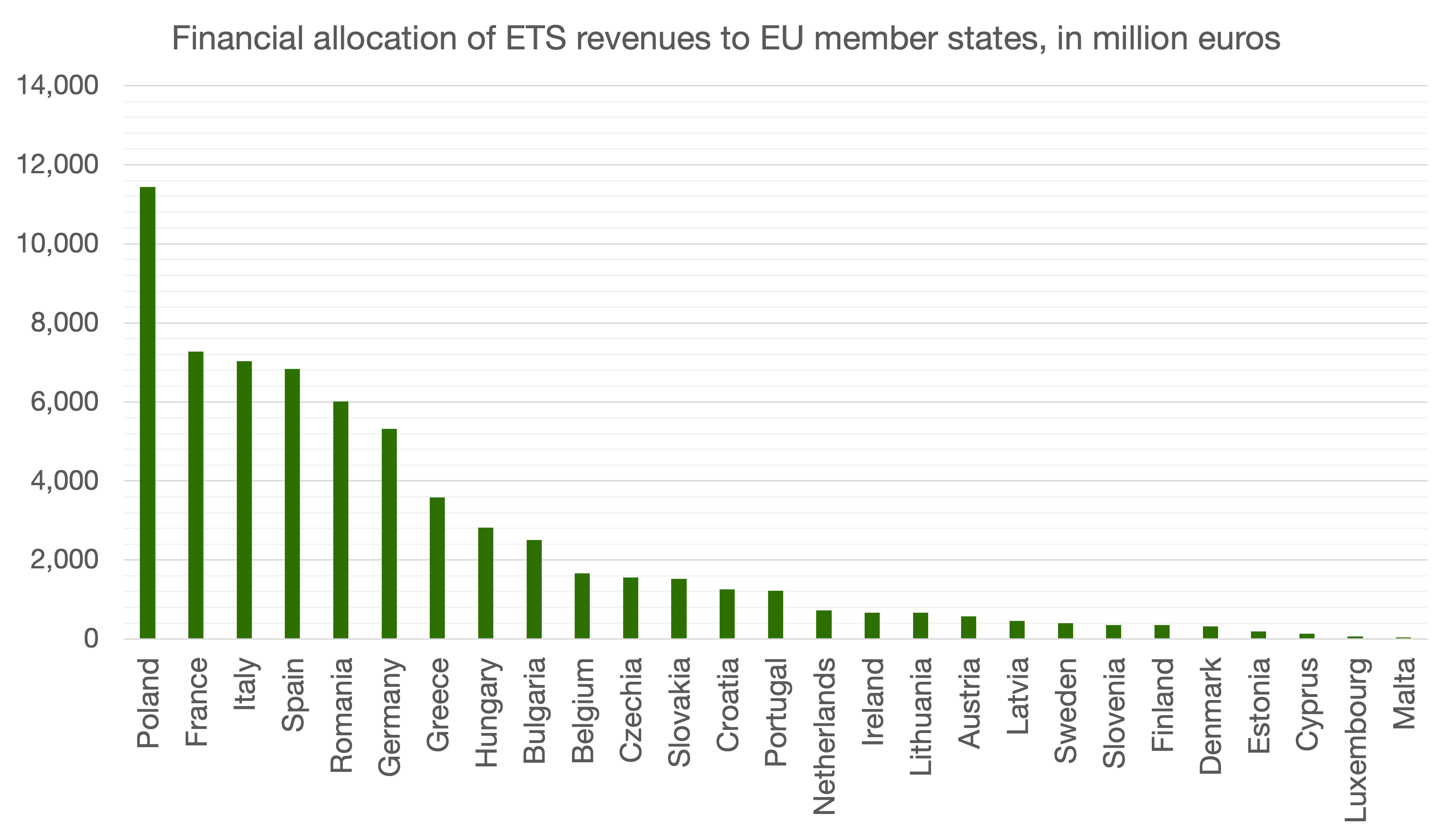

The Social Climate Fund: Materialising Just Transition Principles?

Created on 11-07-2023

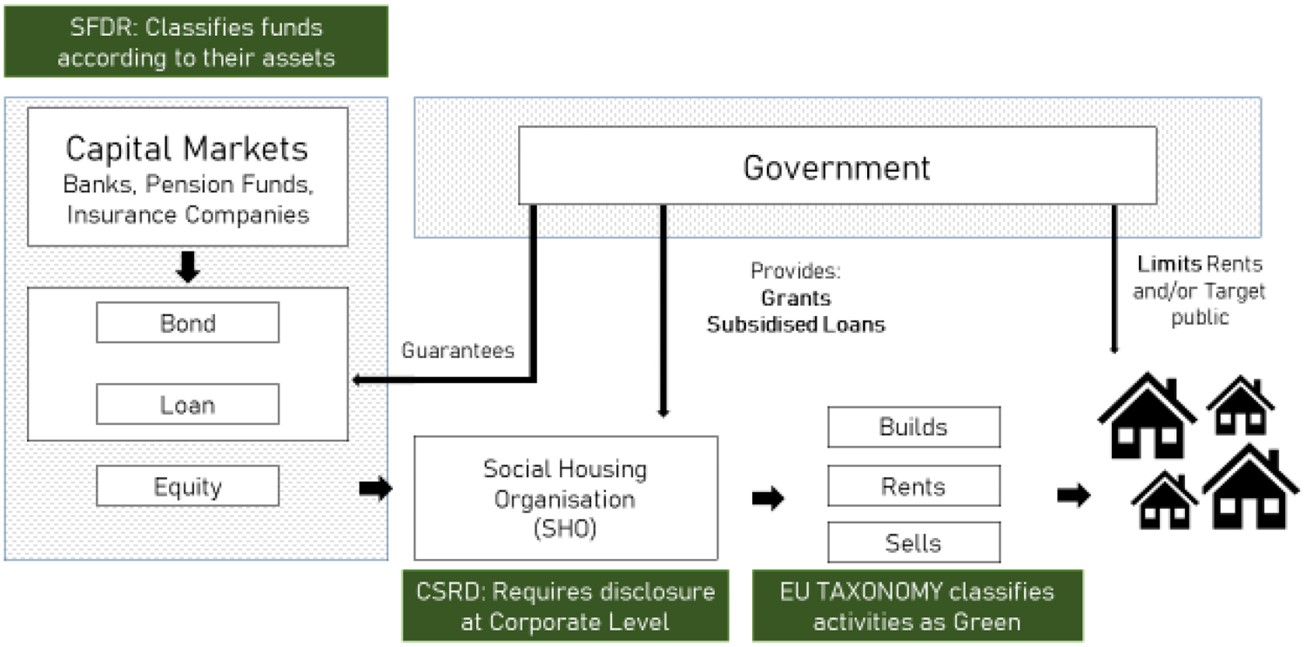

ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

A Combined Energy Efficiency and Levelling Up Scheme: the Dutch ‘Volkshuisvestingsfonds’

Created on 25-09-2024