Area: Community participation

Defining deliberative democracy

Deliberative democracy is a form of democracy that emphasizes the role of discussion and deliberation in the decision-making process. Unlike traditional democratic models that prioritize voting and the aggregation of preferences, deliberative democracy focuses on the quality and process of debate among citizens. The core idea is that through reasoned argument, dialogue, and the exchange of ideas, participants can reach more informed, reflective, and legitimate decisions.

In a deliberative democracy, participants are encouraged to engage in discussions that are open, equal, and inclusive. This means that all participants have an equal opportunity to speak, be heard, and influence the outcome. The deliberative process typically involves several key components.

Key components of deliberative democracy

- Inclusiveness: Ensures that all those affected by a decision have the opportunity to participate in the deliberation, including marginalized and minority voices (Rasmussen, 1994).

- Reason-giving: Expects participants to provide reasons for their positions and engage with the reasons provided by others, fostering understanding, social learning, and respect.

- Respect and civility: Essential requirements for a respectful and civil exchange of ideas, listening to each other, and refraining from personal attacks.

- Informed and rational discourse: Encourages participants to have access to relevant information and engage in critical thinking to evaluate different arguments.

- Consensus-orientation: Despite possible conflicting and plurality of views and values on the issue under scrutiny it is crucial to reach decisions that reconcile and are acceptable to all participants, or at least to the majority, while respecting minority opinions. It therefore has transformative potential.

Deliberative democracy aims to harness the "forceless force of the better argument" (Habermas, 1975, 108) in an environment that is tolerant of dissent. It can take various forms, including citizens' assemblies, deliberative polls, and participatory budgeting, designed to facilitate structured and meaningful dialogue among diverse groups of people. This approach helps form a “we-perspective” (Rostbøll, 2008).

Positioning deliberative democracy

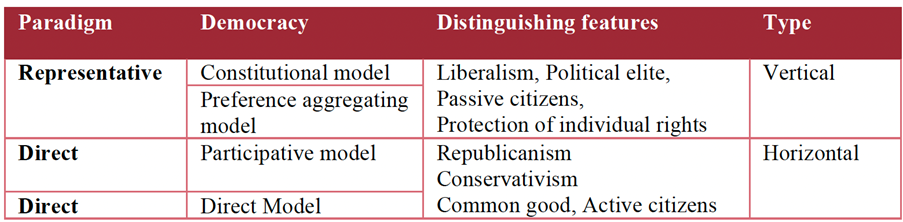

If we were to position deliberative democracy within the spectrum of existing democratic models (see image 1), it would likely fall between direct democracy and representative democracy. Direct democracy aims to include an impractically large number of participants, while representative democracy often creates significant distances between representatives and those they represent. For Habermas, the essence of democracy lies in discourse (Habermas, 1996), rejecting the utilitarian approach. A deliberative approach does not need to ignore the practicalities of representative democracy but can address the “imbalance between the vertical and the horizontal dimensions of democracy” (Hansen et al., 2016).

The guiding principles of deliberative democracy

Deliberative democracy finds its guiding principles in discursive ethics as it prioritizes reasoned dialogue and inclusive discourse to achieve collective decision-making that respects the inherent worth and equality of all participants. Both Habermas and Dryzek emphasize that ethical discourse and rational deliberation are essential for achieving mutual understanding and consensus in democratic processes.

Habermas is a central figure in developing the theory of discourse ethics, which forms the philosophical foundation for his concept of deliberative democracy. One key aspect is communicative rationality. Habermas’s concept of communicative rationality emphasizes the role of reasoned discourse in achieving mutual understanding and consensus. In ´The Theory of Communicative Action´(1984), Habermas argues that democratic legitimacy arises from free and open dialogue where participants justify their claims through rational arguments. This idea is essential for deliberative democracy, which relies on inclusive and reasoned discussion to make collective decisions. It was Habermas who introduced the notion of the ideal speech situation (1983), where communication is free from coercion and participants have equal opportunities to speak and be heard. This ideal situation is crucial for ethical discourse, ensuring that decisions are reached through fair and unbiased deliberation. In his work (Between Facts and Norms, 1996), Habermas connects discourse ethics directly to democratic theory by arguing that legitimate laws and policies must be justified through public deliberation. He contends that the legitimacy of democratic decisions hinges on the quality of the deliberative process, aligning with the core principles of deliberative democracy.

John Dryzek extends Habermas's ideas, emphasizing practical and inclusive aspects of deliberative democracy. He argues that legitimate democratic decision-making requires incorporating diverse discourses and perspectives (1990). He builds on Habermas's idea of communicative rationality, advocating for a democracy that is open to multiple forms of communication and expression, thus ensuring a more inclusive and representative deliberative process. Dryzek (2006) argues for the empowerment of marginalized voices in deliberative processes. He stresses that genuine deliberative democracy must engage all affected individuals, reflecting Habermas’s ethical concern for inclusivity and equality in discourse. Additionally, Dryzek (2010) focuses on the practical aspects of implementing deliberative democracy. He discusses real-world applications and challenges, drawing from Habermas’s theoretical framework but adapting it to diverse political contexts. Dryzek emphasizes the importance of creating institutional arrangements that facilitate effective and fair deliberation.

Both Habermas and Dryzek see discourse ethics as integral to the functioning of deliberative democracy. Habermas provides the theoretical and ethical groundwork, while Dryzek offers practical insights and adaptations for real-world democratic practices. Together, they underscore the importance of rational, inclusive, and ethical deliberation in achieving democratic legitimacy.

The relevance of deliberative democracy in affordable and sustainable housing

Deliberative democracy is particularly relevant to the development of affordable and sustainable housing policies. Housing issues are complex and multifaceted, involving economic, social, environmental, and political dimensions. A deliberative approach to housing policy can address these complexities in several ways. By including a wide range of stakeholders—residents, developers, policymakers, and community organizations—deliberative processes ensure that the voices of those most affected by housing decisions are heard. This inclusivity can lead to more equitable and just outcomes. Deliberative democracy emphasizes the importance of reasoned debate and evidence-based decision-making, which is crucial in housing policy where decisions need to balance affordability with sustainability, and economic feasibility with social equity. Achieving consensus can help build broad-based support and legitimacy for the resulting policies, particularly important in contentious areas such as land use planning, zoning regulations, and the allocation of resources for housing development. The deliberative process encourages creative problem-solving by bringing together diverse perspectives, leading to innovative solutions that might not emerge from more traditional, top-down decision-making processes. Especially when it comes to issues that have a direct and significant impact on everyone's lives, such as housing policy. Decision-making should not just fall into the remit of technocrats and politicians. The housing question should be opened up to public deliberation, as has happened in other spheres of urban planning and governance with experiences like participatory budgeting in Belo Horizonte or Porto Alegre (Baiocchi, 2005; Cabannes, 2004; Melo & Baiocchi, 2006).

Deliberative democracy and public reasoning can be used as a means for more representative and equitable housing-led regeneration processes to ensure that projects are in the best interests of those directly affected and maximise social value. The democratisation of housing management can also be attained by incorporating the principles of deliberative democracy. Giving tenants more control over decision-making can have a transformative impact on the long-term sustainability of housing schemes. Sustainable housing requires long-term thinking, and deliberative democracy fosters a more holistic approach to policy-making, planning and building, taking into account the long-term consequences of decisions and the need for sustainable development.

Possible implementation in the housing landscape

Clapham & Foye (2019) identify three levels in which deliberative democracy can be a powerful tool to facilitate housing-related decision-making processes and evaluate housing outcomes:

Dwelling scale: Standards developed to set minimum qualities of the housing stock should incorporate a component informed by bottom-up consultation that incorporates residents’ views on what constitutes a decent home. In this way, publicly discussed aspirations and needs are brought together with more quantitative and technical considerations. One example of this is the Living Home Standard, developed by Shelter (2016) following a broad consultation process in which hundreds of members of the public were convened in focus groups and workshops to define what a home means and to identify its key and most valuable elements. In doing so, the process provided the elements necessary for a meaningful exchange, public discussion and debate between participants, in which diverse viewpoints were included.

Neighbourhood scale: In his reflections on the ideal size of a city, Aristotle determined a roughly appropriate size based on various characteristics that would ensure its self-sufficiency. Just as important as having access to resources, in his view, was the successful administration of a city, which had to be linked to democratic processes and wellbeing considerations (Lianos, 2016). In such an arrangement, the debate is direct, open and face-to-face. In modern-day terms, at the neighbourhood level, the local context enables a type of relationship between citizens and the city in which they recognise themselves and have a tangible interest in the issues under discussion because it is at the local scale where consequences of ill-considered decisions can have a greater impact. Sennett (2018) identifies similar characteristics in Jane Jacobs’ understanding of a well-functioning neighbourhood as the generative unit of a vibrant and thriving city. In this case, direct democracy practised at the neighbourhood level would constitute, by addition of the parts, a more democratic city. At this level, the relevant stakeholders are expected to play an active role in the participation process because of their attachment to the place. Examples include neighbourhood renewal processes, urban planning and development projects, refurbishment of housing estates or the creation of a local plan.

National scale: Although often seen as terrain for more vertical forms of democratic arrangements such as representative democracy, Clapham & Foye (2019) propose deliberative democratic forums held at a national level to discuss highly political issues around housing, such as property tax relief, lad value tax abatements, house price inflation, rent reform, etc. This view aligns with that of Marcuse & Madden (2016), who call for the democratisation of the housing system as a necessary step in devising transformative solutions to the housing crisis worldwide. In order to rebalance the existing power relations, decision-making control should be handed over to those who are “the true experts on their own housing” (p.212), i.e. to those who are oppressed by the current system. A process that relies on a truly democratised housing system, i.e. a system that is open and inclusive enough to allow for broader democratic scrutiny and ensure that the input of non-experts and historically disempowered communities is accounted for.

In summary, deliberative democracy provides a framework for developing a housing system that is not only affordable and sustainable but also inclusive, equitable, and widely supported by the community. By fostering open, informed, and respectful dialogue, deliberative processes can lead to more effective and legitimate housing solutions that meet the diverse needs of society.

References

Baiocchi, G. (2005). Militants and Citizens: The Politics of Participatory Democracy in Porto Alegre. Stanford University Press.

Cabannes, Y. (2004). Participatory budgeting: a significant contribution to participatory democracy. Environment and Urbanization, 16(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780401600104

Clapham, D., & Foye, C. (2019). How should we evaluate housing outcomes? UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, 1–31.

Dryzek J. S. (1990). Discursive Democracy: Politics, Policy, and Political Science. Cambridge University Press.

Dryzek, J. S. (2006). Deliberative Global Politics: Discourse and Democracy in a Divided World. Polity.

Dryzek, J. S. (2010). Foundations and Frontiers of Deliberative Governance. Oxford University Press.

Habermas, J. (1975). Legitimation Crisis. Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1983). Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. Cambridge. MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action, Volume I. Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action, vol. 2, Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason. Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (1996). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Polity Press.

Hansen, H. P.; von Essen, E. & Sriskandarajah, N. (2016). Citizens, Values and Experts: Stakeholders: The Inveigling Factor of Participatory Democracy. Routledge.

Lianos, T. P. (2016). ARISTOTLE ON POPULATION SIZE. History of Economic Ideas, 24(2), 11–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44806062

Marcuse, P., & Madden, D. (2016). In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis. Verso Books. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6PXLsgEACAAJ

Melo, M. A., & Baiocchi, G. (2006). Deliberative Democracy and Local Governance: Towards a New Agenda. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30(3), 587–600. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00686.x

Sennett, R. (2018). Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City. Penguin Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.5666735

Rasmussen, D. M. (1994). How is Valid Law Possible? A Review of Faktizität und Geltung by Jürgen Habermas. Philosophy and Social Criticism. 21–44.

Rostbøll, C. F. (2008). Deliberative freedom: Deliberative Democracy as Critical Theory. State University of New York Press.

Created on 19-06-2024 | Update on 23-10-2024

Related definitions

Affordability

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 27-08-2021 | Update on 20-04-2023

Read more ->Co-creation

Area: Community participation

Created on 16-02-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Housing Governance

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 16-02-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Participatory Approaches

Area: Community participation

Created on 17-02-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Community Empowerment

Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Just Transition

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-06-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Urban Commons

Area: Community participation

Created on 14-10-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Community-led Housing

Area: Community participation

Created on 05-10-2023 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Post-occupancy Evaluation

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 22-10-2023 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Public-civic Partnership

Area: Community participation

Created on 08-11-2023 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Related cases

No entries

Related publications

No entries