Homelessness

Area: Policy and financing

Throughout history, many different terms have been used to refer to people living on the streets[1], and since the 1980s “homeless” has been the most commonly used expression. The exact number of homeless people is usually difficult to determine due to different typologies and definitions applied across the countries.

Homelessness is a “manifestation of extreme poverty and social exclusion, it reduces a person’s dignity as well as their productive potential and is a waste of human capital” (Baptista & Marlier, 2019). It is a symptom of globalisation and systemic changes in the world economy (Ferenčuhová & Vašát, 2022). In 1995, Brian Cooper distinguished between absolute and relative homelessness, absolute being people with no access to shelter or the roof over their heads, while relative homelessness he divided into three degrees. Primary homelessness is “people moving between various forms of temporary or medium-term shelter”, secondary are “people constrained to live permanently in single rooms in private boarding houses” and third degree are “housed but with no condition of a “home”, e.g., security, safety, or inadequate standards” (Bilinović Rajačić & Čikić, 2021; Cooper, 1995; Tipple & Speak, 2005 ).

Ferenčuhova & Vašat (2022) frame homelessness as a "structurally determined phenomenon linked to the functioning of economic and political regimes and their diversity", and that one of the causes of growing homelessness is the rapid modernisation of society. The United Nations (UN) (2009) used to distinguish between two categories of homeless people, primary (living on the street) and secondary (frequent moves, long-term sheltering, people with no fixed abode), and today the UN and most EU countries adopt a definition developed by the European Federation of Organisations Working on Homelessness (FEANTSA), which recognises different forms of homelessness and living situations within the framework of the European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Market Exclusion (ETHOS) developed in 2005. According to the typology ETHOS, there are four categories of homelessness: roofless, houseless, insecure housing and inadequate living conditions. These categories are each subdivided into housing categories, which in turn are subdivided into types of living situations (FEANTSA, 2017). “ETHOS light” typology is a simplified version of ETHOS typology with fewer categories, and is mainly used for statistical purposes and comparisons across EU countries.

According to the ETHOS typology, there are many forms and manifestations of homelessness, and homelessness is more than just not having a place to sleep. There are some criticisms of the ETHOS typology, for example, that there is no clear distinction between homelessness and housing exclusion (Bilinović Rajačić & Čikić, 2021). A typology based on the risk of homelessness could be acute, immediate or potential, while a typology based on frequency and duration could be temporary, episodic or chronic (Bilinović Rajačić & Čikić, 2021). Many other typologies and definitions of homelessness are found in literature, including various theoretical streams on the causes of homelessness. Some of the main causes of homelessness in the EU are the lack of affordable housing supply and changes in the labour market, i.e., short-term and precarious employment, low wages, unemployment and long-term unemployment (Baptista & Marlier, 2019). No matter what typology or definition is applied, the homeless represent the population of absolute poverty that includes the inability to meet basic human needs, including housing (Kostelić & Peruško, 2021).

The Lisbon Declaration of 2021 is a document that builds on the European Pillar of Social Rights and was signed by the relevant European institutions and Member States to work together to end homelessness. It addresses many aspects to address homelessness by recognising where homelessness is most prevalent, and who is most affected by it. The Declaration also states that existing institutions in EU Member States currently lack adequate responses and capacity (Lisbon Declaration, 2021).

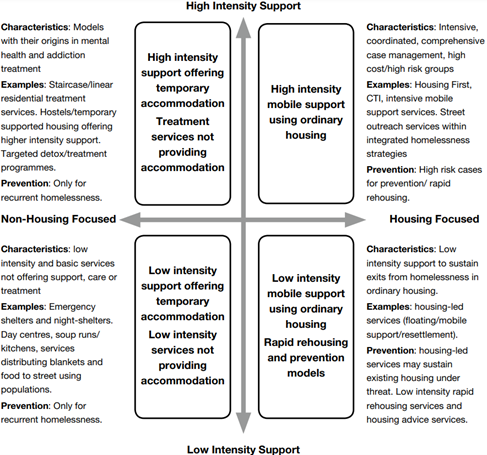

When it comes to ending homelessness and developing homeless reintegration programmes, there are two main approaches: the “Staircase” programme (treatment-oriented) which has an established history of application, and the innovative “Housing First” programme, which is less represented in practice but increasingly represented (housing-oriented). According to Pleace et al. (2018), services for the homeless across EU countries could be divided into typologies (Figure 1). According to this figure, Croatian service providers would mostly fit into the third quadrant: non-housing focused and low intensity support, but according to Pleace et al. (2018), other Eastern (and Southern) European countries are likely to have the same type of support and this type of service is the most common in Europe, which means overnight shelters, food distribution daycentres etc. In post socialist countries, homelessness is also understood as an emerging new social risk due to increasing mortgage default rate, which was evident in the aftermath of the Global financial crisis of 2008 (Horvat & Bežovan, 2024).

[1] vagabonds, tramps, beggars, itinerant people, homeless people

References

Baptista, I., & Marlier, E. (2019). Fighting homelessness and housing exclusion in Europe: A study of national policies (Issue October).

Bilinović Rajačić, A. & Čikić, J. (2021). Beskućništvo teorija, prevencija, intervencija. In Paper Knowledge. Toward a Media History of Documents.

Cooper, B. (1995). Shadow people: the reality of homelessness in the 90's. Sydney: Sydney City Mission

FEANTSA (2017). European Typology of Homelessness Ethos and Housing Exclusion. Downloaded from: https://www.feantsa.org/download/ethos2484215748748239888.pdf (13.7.2022)

Ferenčuhová, S., & Vašát, P. (2022). Ethnographies of urban change : introducing homelessness and the post-socialist city. Urban Geography, 42(9), 1217–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1930696

Horvat, M. & Bežovan, G. (2024). Sustainability and Capacity Analysis of Croatian Homeless Service Providers. European Journal of Homelessness, Vol. 18, No. 2, ISSN 2030-2762 / ISSN 2030-3106 online

Kostelić, K. & Peruško, E. (2021). Skupine čimbenika i njihov utjecaj na važne životne odluke: beskućnici u Puli [Groups of factors and their influence on important life decisions: homeless people in Pula], Ljetopis socijalnog rada 2021., 28 (1), 273-299

Lisbon Declaration. (2021). Lisbon Declaration on the European Platform on Combatting Homelessness. https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=24120&langId=en, (2.8.2022)

Pleace, N. et al. (2018). Homelessness Services in Europe - Comparative Studies on Homelessness. European observatory on homelessness.

Tipple, G., & Speak, S. (2005). Tipple and Speak, Definitions of homelessness in developing countries. Habitat International, 29(2), 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2003.11.002

Created on 21-10-2024 | Update on 23-10-2024

Related definitions

Affordability

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 27-08-2021 | Update on 20-04-2023

Read more ->Just Transition

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-06-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Related cases

No entries