ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

Over the last decades, ESG debt issuance, through green, social or sustainability-linked loans and bonds has become increasingly common. Financial markets have hailed the adoption of ESG indicators as a tool to align capital investments with environmental and social goals, such as the decarbonisation of the social housing stock. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the green debt market has experienced a 50% growth over the last five years (CBI, 2021). However, the lack of clearly established indicators and objectives has tainted the growth of green finance with a series of high-level scandals and accusations of green-washing, unjustified claims of a company’s green credentials. For example, a fraud investigation by German prosecutors into Deutsche Bank’s asset manager, DWS, has found that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments despite this being stated in the fund’s prospectus (Reuters, 2022).

To curb greenwashing and improve transparency and accountability in green investments, the EU has embarked on an ambitious legislative agenda. This includes the first classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities: the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation 2020/852). The Taxonomy is directly linked to the European Commission’s decarbonisation strategy, the Renovation Wave (COM (2020) 662), which relies on a combination of private and public finance to secure the investment needed for the decarbonisation of social housing.

Energy efficiency targets have become increasingly stringent as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its successive recasts (COM(2021)) have been incorporated into national legislation; see for example the French Loi Climate et Resilience (2021-1104, 2021). Consequently, capital expenses for SHOs are set to increase considerably. For example, in the Netherlands, according to a Housing Europe (2020) report, attaining the 2035 energy efficiency targets set by the Dutch government will cost €116bn.

Sustainable finance legislation constitutes an expansion of the financial measures implemented by the EU in recent decades to incentivise energy efficiency standards as well as renovations in the built environment. For more detail on prior EU policies, see Economidou et al. (2020) and Bertoldi et al. (2021). The increased connections between finance and energy performance raise specific questions regarding SHOs’ access to capital markets in light of the shift toward ESG.

The rapidly expanding finance literature on green bonds draws from econometric models to explore the links between investors’ preferences and yields (Fama & French, 2007). This body of literature on asset pricing relies on the introduction of non-pecuniary preferences in investors’ utility functions together with returns and risks to explain fluctuations in the equilibrium price of capital. Drawing from a comparison between green and conventional bonds, Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) find evidence of the former being priced at a premium. Similarly, Zerbib (2019) also shows a low but significant negative yield premium for green bonds resulting from both investors’ environmental preferences and lower risk levels. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (Fatica & Panzica, 2021) documents the dependency of premiums on the issuer with significant estimates for supranational institutions and corporations, but not for financial institutions. While these econometric approaches offer relevant insight into the pricing of green bonds and the incentives for issuers and investors, they do not account for the institutional particularities of social housing, a highly regulated sector usually covered by varying forms of state guarantees and subsidisation (Lawson, 2013).

ESG-labelled debt instruments & Related Legislation

Throughout the last two decades, the term ESG finance has evolved to include a large number of financial vehicles of which green bonds have become the most popular (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). In the social housing sector, ESG comprises a broad array of tools from sustainability-linked loans to less conventional forms of finance such as carbon credits. When it comes to bonds, there is a wide variation in the sustainability credentials among the different types. Broadly speaking, green and social bonds are issued under specific ‘use of proceeds’, which means the funds raised must be used to finance projects producing clear environmental or social benefits. The issuance of these types of bonds requires a sustainable finance framework, which is usually assessed by a third party emitting an opinion on its robustness.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are an alternative to ‘use of proceeds’. Funds raised in this manner are not earmarked for sustainable projects, but can be used for general purposes. SLBs are linked to the attainment of certain company-wide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), for example an average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of “C” in an SHO’s housing stock. These indicators and objectives usually result in a price premium for Sustainable Bonds, or a rebate in interest rates in the case of SLBs or sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021).

While there are international standards for the categorisation of green projects such as the Green Bond Principle or the Climate Bonds Strategy, strict adherence is optional and there are few legally-binding requirements resulting in a large divergence in reporting practices and external auditing. To solve these issues and prevent greenwashing, the EU has been the first regulator to embark on the formulation of a legal framework for green finance through a series of acts targeting the labelling of economic activities, investors, corporations and financial vehicles.

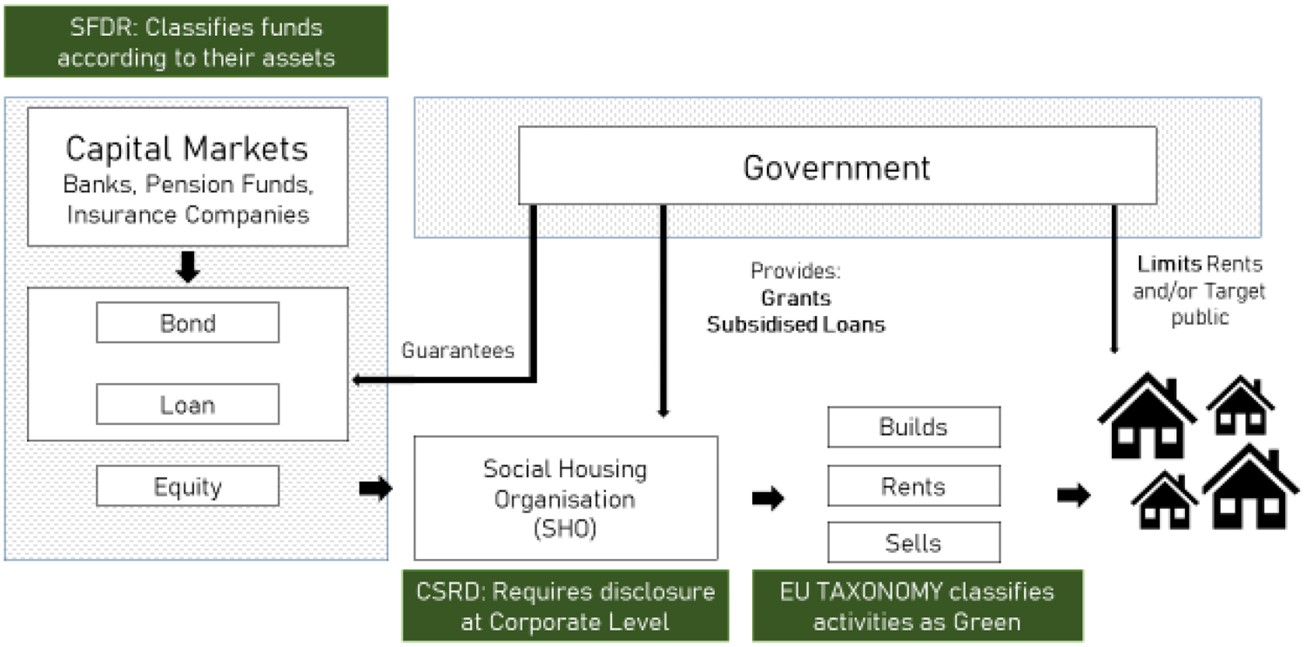

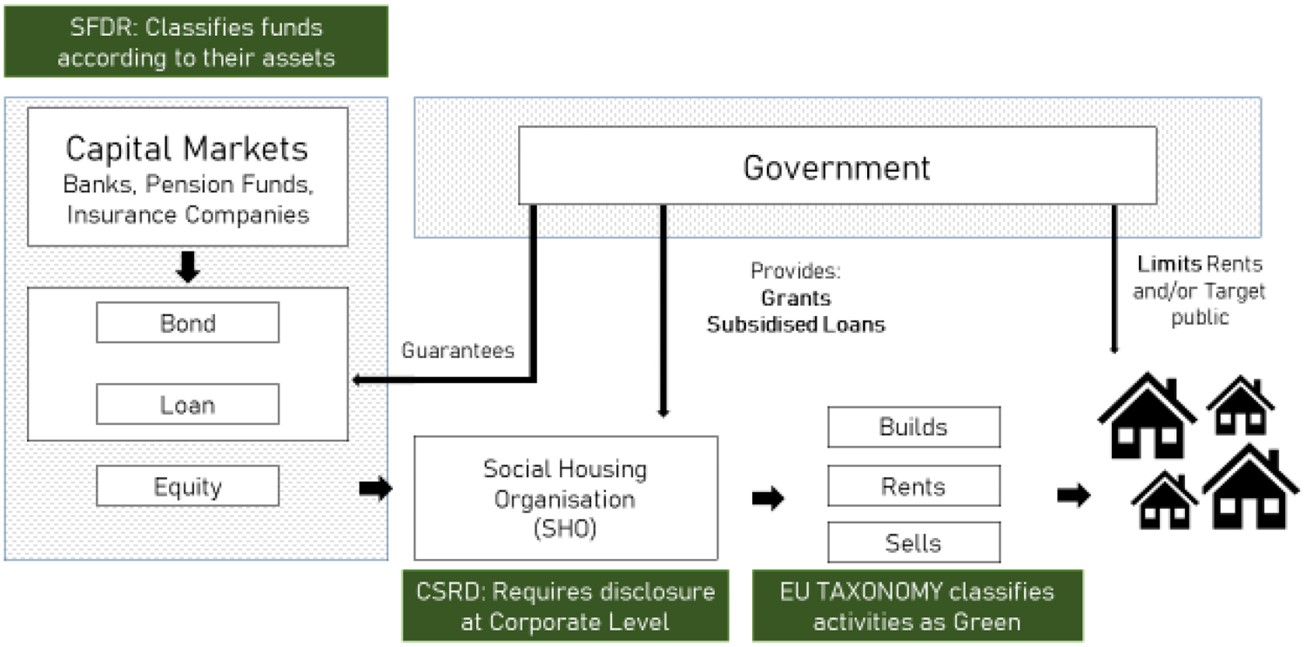

First, the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) is the cornerstone of this new legislation since it classifies economic activities attending to their alignment with the objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD). When it comes to housing, the EU Taxonomy requires specific energy efficiency levels for a project to be deemed ‘taxonomy aligned’. Second, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) mandates ESG reporting on funds, which tend to consist of exchange-traded collections of real assets, bonds or stocks. Funds are required to self-classify under article 6 with no sustainability scope, ‘light green’ article 8 which incorporates some sustainability elements, and article 9 ‘dark green’ for funds only investing in sustainability objectives. Under the SFDR, which came into effect in January 2023, fund managers are required to report the proportion of energy inefficient real estate assets as calculated by a specific formula taking into account the proportion of ‘nearly zero-energy building’, ‘primary energy demand’ and ‘energy performance certificate’ (Conrads, 2022). Third, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)(COM(2021) 189) increases disclosure requirements for corporations along Taxonomy lines. This legislation, which came into effect in 2023, will be progressively rolled out starting from larger and listed companies and expanding to a majority of companies this decade. Provisions have been made for charities and non-profits to be exempt. However, one of the key consequences of disclosure requirements over funds through the SFDR is its waterfall effect; that is the imposition of indirect reporting requirements as investors pass-on their reporting responsibilities to their borrowers. Fourth, the proposed EU Green Bonds Standards (EU-GBS) COM(2021) 391 aims to gear bond proceedings toward Taxonomy-aligned projects and increase transparency through detailed reporting and external reviewing by auditors certified by the European Security Markets Authorities (ESMA). The main objectives of these legislative changes is to create additionality, that is, steer new finance into green activities (see Figure 1).

While this new legislation is poised to increase accountability and transparency, it also aims to encourage a better management of environmental risks. According to a recent report on banking supervision by the European Central Bank (ECB), real estate is one of the major sources of risk exposure for the financial sector (ECB, 2022). This includes both physical risks, those resulting from flooding or drought and, more relevant in this case, transitional risks, that is those derived from changes in legislation such as the EPBD and transposing national legislation. The ECB points to the need for a better understanding of risk transmission channels from real estate portfolios into the financial sector through enhanced data collection and better assessments of energy efficiency, renovation costs and investing capacity. At its most extreme, non-compliance with EU regulations could result in premature devaluation and stranded assets (ECB, 2022).

In short, the introduction of reporting and oversight mechanisms connects legislation on housing’s built fabric, namely the EPBD, to financial circuits. On the one hand, the EU has been strengthening its requirements vis-à-vis energy efficiency over the last decades. The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) suggested the introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by Member States (Economidou et al., 2020), a rationale followed by France and the Netherlands for certain segments of the housing stock. Currently, policy-makers are debating on whether the EPBD’s recast (COM/2021/802) should incorporate MEPS and make decarbonisation an obligation for SHOs across the EU. On the other hand, legislation on green finance aims to produce incentives and oversight over investments in energy efficient renovation and new build, mobilising the private sector to cater to green projects (Renovation Wave (COM(2020) 662)).

A.Fernandez. ESR12

Read more

->

Broadwater Farm Urban Design Framework

Created on 26-07-2024

The Broadwater Farm Estate

The estate, built in the full swing of modernism, is a paragon of the movement’s defining characteristics. The building density is notably high compared to the surrounding single-family terraced houses. There is a clear separation between vehicles and pedestrians, with platforms and deck accesses. The ensemble comprises twelve high-rise precast concrete blocks and towers, which extend over a public-owned site of 18 hectares, which is unusually large by today’s standards. Facilities were also provided for residents, offering them the essential amenities. Upon completion in the early 1970s, the estate comprised 1,063 flats and was home to between 3,000 and 4,000 residents.

As was the case with numerous other modernist housing estates across the country, Broadwater Farm was significantly affected by the seminal work of Alice Coleman, Utopia on Trial (1985) on the concept of “defensible space”. Proponents of this theory posited that design had a deterministic impact on crime rates and social malaise in low-income urban communities. Although Coleman's study faced harsh criticism from academics for its questionable methodology and oversimplification of complex social problems (Cozens & Hillier, 2012; Lees & Warwick, 2022), her recommendations led to the implementation of a multi-million-pound government-funded programme for remedial works in thousands of social housing blocks nationwide; known as the DICE (Design Improvement Controlled Experiment) project. Broadwater Farm was targeted by the programme after it attracted considerable attention following the serious riots that occurred at the estate in 1985 (Stoddard, 2011). A number of initiatives were undertaken with the objective of regenerating and improving the quality of the built environment, with the earliest works beginning in 1981. Under the DICE project, a significant number of the overpass decks that connected the estate on the first floor were demolished on the grounds that they were conducive to the formation of poorly lit and isolated areas that were facilitating criminal activity and anti-social behaviour (Severs, 2010).

In the wake of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, new fire safety regulations and inspections have been introduced, resulting in two blocks of flats being deemed unfit for habitation (BBC, 2022). The Large Panel System (LPS), which was commonly used in the 1960s, has been identified as the primary cause for the demolition of the Tangmere and Northolt blocks due to the significant risk of collapse in the event of a fire. These essential repairs will be part of the largest refurbishment project ever undertaken in the estate. It will comprise a combination of retrofitting, redevelopment and infill, resulting in an increase in the number of housing units and a significant enhancement of the urban layout and public spaces across its 83,000 sq. m.

The Urban Design Framework (UDF) is a comprehensive document that sets out a series of actionable and tangible improvements for the estate. Produced by Karakusevic Carson Architects (2022) and commissioned by the Haringey Borough Council, the UDF serves as a masterplan for the ongoing regeneration of the estate. This document is the result of an extensive stakeholder involvement process. It proposes a series of five urban strategies that, taken together, provide a blueprint for holistic regeneration. These strategies account for the short, medium and long-term development of both the estate and its community.

Given the substantial size of the complex, the scale of the surrounding neighbourhood, and the intricate web of relationships within it, long-term planning holds significant importance. These aspects were emphasised through the proposed interventions that enhance the connections between the dwellings and the urban context. The impact of the estate on the surrounding area and the need for a cohesive urban landscape are addressed through designs that integrate the estate into the city fabric, rather than isolating it. The improvement plan includes the construction of new residential units through the redevelopment of the blocks earmarked for demolition and the refurbishment of the remaining blocks. The architectural firm has developed a "bank of projects," a comprehensive repository of proposed interventions arising from engagement with the community as well as a site analysis, which is organised around five core principles: streets, open spaces, ground floors, character, and homes.

Resident engagement

The inhabitants were actively involved in the creation of the UDF. A series of community engagement events, held between 2020 and 2021, provided a platform to gather the voices of residents and enabled planners to better understand their aspirations and needs, identify the key improvements required, and initiate the design process that would incorporate their views into the masterplan. This process was complemented by the establishment of the Community Design Group (CDG), formed by residents and community members who not only expressed a desire, but also demonstrated the capacity, to assume a more active role in the design process. In addition, the council has set up a website that documents and displays the schedule, events, latest news and updates on the ongoing regeneration process. This website provides comprehensive information for residents, the general public, and any interested parties seeking to gain insight into the current status of Broadwater Farm.

Placemaking strategy

In contrast to pervasive narratives about the flawed design of council estates, the spatial qualities and existing sense of belonging within the community were identified as the starting points for the placemaking strategy. The original configuration of the estate was conceived around community facilities and courtyards, which have been retained, augmented, formalised, and linked by a circuit of pedestrian and cycle paths. The deficiencies of the original design, such as the anonymous and segregated ground floor, have been addressed by establishing a network of public spaces that prioritise human scale and facilitate movement throughout the estate. These new public spaces facilitate social interaction, providing areas of activity complemented by indoor amenities and spaces for local retailers. In this way, the ground level becomes an anchor for diverse activities aimed at enhancing the sense of security.

The masterplan revolves around five principles which in turn incorporate a series of strategies:

1. Safe and Healthy Streets: The improved design shifts away from 'streets in the sky' to enhance street accessibility. It promotes intermodal transport with a new bus route into the estate and the addition of cycle lanes. The road network within the estate has been simplified to be more efficient and encourage walking. A "green" street connects key community facilities and green spaces. Overall wayfinding is enhanced through better street lighting, improved block entrances, and designated car-free areas. Part and parcel of reactivating the ground floor is creating opportunities for new activities through a redesign aimed at more efficient parking solutions to meet current needs.

2. Welcoming + Inclusive Open Spaces: Although the estate features several courtyards and open areas, residents have expressed a feeling of being in a “concrete jungle”, as noted in the community brief. The proposed improvements focused on enhancing the existing courtyards to ensure accessibility and facilitate various activities. In addition, a new community park is planned at the heart of the estate as part of the redeveloped area, designed to be a versatile and welcoming space for current and future residents alike. A hierarchy of shared and public spaces has been redesigned to create a seamless transition into and out of the estate. This seamless and unified experience of the public realm is enabled by specific elements such as play areas and seating that allow people of all ages to socialise and interact in an informal yet purposeful manner.

Workshops were conducted with specific population groups, including young women and girls or older residents, to ensure that the future estate will be as inclusive as possible. Key topics such as perceived safety in the communal areas, activities and sports facilities, as well as overall design considerations, were discussed during these sessions.

3. Ground Floors with Activity: A significant design flaw in the existing estate was the poorly lit areas adjacent to the garages that dominated the ground floor of the blocks — a common design feature in residential architecture of the time. Residents involved in the process pointed out the importance of increasing the sense of security when moving around these areas. A street-based design that activates the ground floor by enabling a greater variety of activities was central to the strategy. Alongside a clearer street layout and improved block entrances, bike racks, bin storage, and opportunities for non-residential and community uses were proposed to benefit both residents and the wider community. By repurposing areas previously used mainly for car parking into active spaces and by enhancing frontages with residential, commercial or community spaces, clear thresholds and boundaries are created to promote permeability and smooth transitions. Community facilities and local businesses are strategically located at corners and key activity nodes, facilitating passive surveillance and overlooking the public realm. The choice of materials also contributes to opening up the ground level; glazed lobbies and entrances connect indoor communal areas with adjacent outdoor spaces visually. Similarly, secondary entrances to existing blocks will be used to balance their function and prevent the creation of hidden or less frequented areas. Improved public lighting, new signage and a control system complement these strategies.

4. Broadwater Character & Scale: The architectural style known as Brutalism played a significant role in popularising the 'problem estate' narrative in Britain. This style was embraced by many of the country's modernist architects, leading to its prevalence in the social housing built during that period. Characterised by the predominant use of concrete, this style was celebrated by critic and advocate Reyner Banham for its memorable image, a clear exhibition of structure and honest expression of the material (Boughton, 2018). The monumentality and stark aesthetics of Brutalism provided an ideal setting for experimentation in the vast estates that were built during the latter half of the 20th century. These characteristics are evident in the design of Broadwater Farm.

Broadwater’s design framework acknowledges the latent potential of the existing architecture while addressing issues of materiality, building height, the links and spatial relationships between the infilled and redeveloped areas and the connection between the estate and its surroundings. The boundaries of the estate were revised to address the issue of it being perceived as an isolated entity, which was a common problem with many modernist estates. This was due to the fact that they were often of a particular size and density, which set them apart from their neighbours. In order to create a seamless transition with the surroundings, clear entrances to the estate are proposed, new materials are used that better match those of the vicinity, and a massing strategy is employed to avoid abrupt transitions in building heights.

The character of the estate was approached in a manner reminiscent of Kevin Lynch’s (1964) five elements of the city —paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks—, with particular emphasis on their importance in establishing a sense of place and enhancing the legibility of the urban environment. The proposal has engaged in a meticulous study of the local context, re-signifying existing elements such as the Kenley Tower, which has been retained as the tallest mass in the ensemble, in order to maintain its landmark character.

5. Good Quality Homes: The new blocks, arranged in courtyards that reflect the existing pattern of the estate, will replace the Tangmere and Northolt blocks. They will occupy a privileged position at the heart of the estate and offer an opportunity to transform the overall look of the scheme. These new blocks, complemented by infill development on nearby sites, will result in the creation of 294 new residential units, representing a net increase of 85 homes. The new dwellings, comprising three and four-bedroom family homes, will be managed by the council and rented out at social rates. A significant proportion of residents who participated in the public consultation highlighted the necessity for larger and more spacious accommodation, particularly for large families. In response to these demands, the design of the new flats incorporates larger and more flexible spaces as a key feature. Those who previously resided in the demolished blocks will be given priority for the new homes.

Furthermore, the introduction of new parks, public spaces, workspaces and a new well-being hub, which will house a doctor's surgery and other services, will help create a more active and dynamic ground floor, with activities that enhance the sense of place and welcome pedestrians. The architects have conducted an analysis of potential infill solutions to activate the ground floor, including the addition of one-bedroom flats that fit into the structural grid of the existing blocks. This in turn addresses the need to create a community that includes people of all ages and family types.

Management & Maintenance

The UDF exemplifies how regeneration projects can address current needs while allowing for future adaptations. This people-centred project fosters a sense of ownership through participation, which is crucial for the sustainability of the intervention. Stewardship is key, especially for the new collective spaces being created. Instead of a deterministic design approach, the framework considers what types of spaces can enhance the overall quality of life. It integrates social, economic, and environmental aspects that define the living and working experience in the area. These considerations are captured in the “Strategy for a Sustainable Neighbourhood.”

The bank of projects is a repository of proposed interventions within the project, illustrating the considerable interest in the long-term effects of the regeneration project and the substantial potential for future development. This section of the framework underscores the necessity for the formulation of a phased, structured and comprehensive planning and delivery strategy that allows for flexibility and input from existing and future residents. Consequently, management and maintenance are regarded as integral aspects of the design, alongside other tangible elements of the built environment.

With an approach strongly focused on creating social value and reducing the disruptive effects of regeneration. The architects have worked with the community to develop a masterplan that emphasises the use of existing assets, minimises demolition and establishes a hierarchy of priorities to maximise the positive impact in the long term.

L.Ricaurte. ESR15

Read more

->