Androniki Pappa

ESR13

She has collaborated with several international studios, gaining professional experience in diverse projects including architectural and interior design, landscape and urban scale projects and masterplans, as well as policy and guideline reports. She has also worked as a researcher in the Hellenic Institute of Architecture and recently as a teaching assistant at the Master in City and Technology, IAAC.

Her research incentives relate to interdisciplinary methodologies towards the concept of participatory planning and engaging urbanism in heritage, working across architecture, art installation, model making, film, ethnography and social history. She has also actively participated in exhibitions, lectures, workshops and conferences as an organizer, researcher and volunteer.

September, 08, 2023

March, 22, 2022

September, 17, 2021

Over the last decades, European cities have been experiencing the decay in the function of ‘the public’, including services and spaces. Owing to privitisation and/or commodification, quality and access to fundamental resources -and rights- is gradually limited further causing social and physical exclusion, especially impacting the least advantaged groups and neighborhoods. In a counteraction, increasing groups of active citizens take action in providing themselves and local communities at large with affordable and non-market access to goods and services, developing urban commons initiatives. Through self-organisation, people are taking temporary or permanent responsibility for their immediate environments, often through social and cultural initiatives; from urban farming to ‘neighbour days’, to renewable energy or housing cooperatives, whilst regenerating buildings, empty plots, parks and sidewalks. These collective actions foment citizenship, create cohesion, are often based on inclusion and solidarity and hence enable people to shape the world they live in in a sustainable manner.

Yet, there is a pitfall of frameworks and guidelines to secure these initiatives from market and urban ‘threats’. Quite the opposite, being mostly instigated by spontaneous activities, they are often in contrast to existing urban planning regulations, and considered illegal, at the time that international directives, such as the United Nations’ Urban Agenda and Agenda for Sustainable Development 2030, call for local participatory policies that revalue active citizenship and involve citizens in the decision-making processes that affect their neighbourhoods and lives.

The aim of this research is to contribute to bridging the knowledge gap between experiences of informal practices, emancipatory policies that aim to engagement and inclusion and design-oriented processes such as placemaking, with the motivation to foment the transformation of public neighbourhood spaces into common spaces managed by local communities in accordance with their needs while being supported by local administrations and design professionals in this regard. To this end, based on theory along with international practices, processes and regulations, this research develops a taxonomic scheme to define and analyse urban commons to be tested in the city of Lisbon and the BIP/ZIP Program. The study will be delivered to the development of an interdisciplinary transferable tool for urban commons addressed to local associations and designers, taking into consideration the collaboration with local administrations.

Reference documents

Urban commons for Sustainable Local Development in priority neighbourhoods

In recent decades many governments across the globe are implementing experimental forms of collaborative governance in urban regeneration as an alternative to the normative neoliberal management of urban resources and its insufficiency to contribute to the construction of affordable and sustainable communities. At a local level, municipalities adapt their development strategies to follow the targets set by international agendas for sustainability, while active communities showcase bottom-up creative and innovative ways to manage the urban commons.

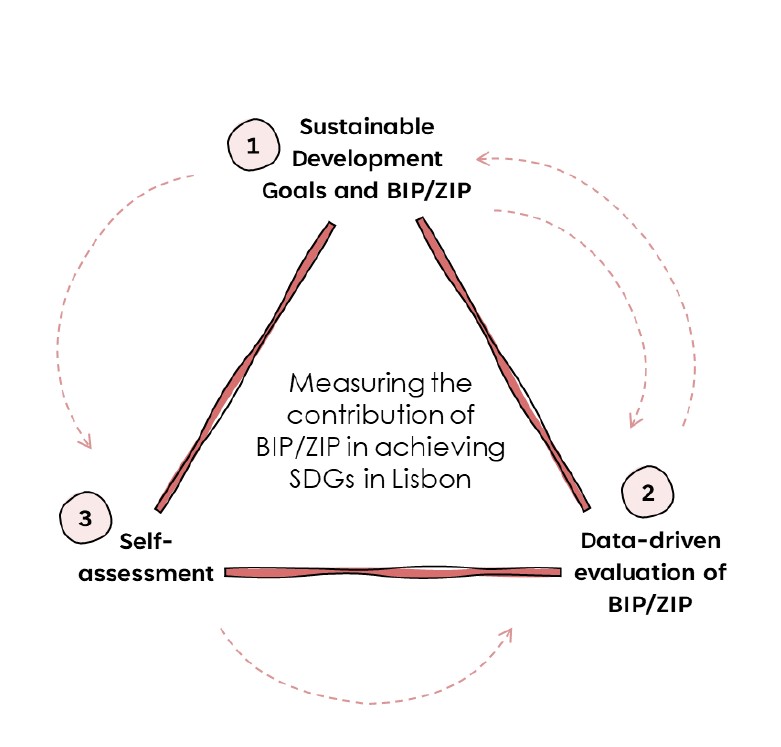

Focusing on ‘priority’ residential neighbourhoods and populations there is an urgency for Sustainable Local Development (SLD) strategies to move beyond climate-and economic-resilient considerations to addressing also very critical social ones. In this frame, citizen engagement with the urban commons can offer a response to contemporary urban challenges through the activation of local networks of relations (commoning) that foster platforms of individual/collective rights. Starting with the city of Lisbon and the BIP/ZIP Program and focusing on the European context, the aim of this research is to investigate how urban commons theory and practices can influence SLD strategies to fortify social and territorial impact in priority neighbourhoods. This requires a preceding study of the two pillars of the research to understand: a. what defines SLD and what are the most appropriate indicators to best describe and measure its impact and b. in what scheme can urban commons in the neighbourhood be represented, including resources, people and social practices and how can their impact be assessed.

To address these questions, the study employs a mixed-methods methodology that initiates with a comprehensive literature review on urban commons and sustainable development to arrive to the identification of indicators and criteria for definition. The theoretical analysis of the two pillars will come together in a common framework and refined during the secondment at the Municipality of Lisbon. Based on this framework, a data-driven approach on the case study of BIP/ZIP (425 projects) will compose a taxonomy, out of which good practices will be drawn and further explored using qualitative methods. Finally, the lessons learnt will be applied through action research in the involvement in ongoing BIP/ZIP projects, as well as the second secondment at Pacte Laboratory in Grenoble.

The study will be delivered to the development of a framework of transferable guidelines for sustainable local development through urban commons that augment the collaboration between different stakeholders to achieve social and territorial cohesion. The results of the research will contribute to the scientific discussion on commons theory and sustainable local development. Starting with BIP/ZIP and Lisbon Municipality and communities, the research will offer itself as a tool for collaborative local development and co-management of the urban commons, contributing to a social-inclusive, sustainable future.

Reference documents

Citizen participation evaluation and urban co-governance: lessons from BIP/ZIP and the world of commons

In recent decades many governments across the globe have implemented participatory and commons-oriented policies in urban regeneration, contributing to the active engagement of citizens in planning at different scales, as well as in co-managing the urban commons.

Ranging from bottom-up good practices of participation that evolve into policies, to top-town initiatives that recognise the benefits of multi-stakeholder governance for local development, the repository of case studies demonstrate an array of experimental planning and governance tools. Among others, these include creative communities, social innovation initiatives, participatory funding, local policies, city regulations or protocols and networks of good practices. One such instrument of public policy is the ongoing BIP/ZIP local development strategy, constituted in 2010 by the Lisbon City Council. Focusing on priority intervention neighbourhoods and zones, BIP/ZIP enables bottom-up citizen participation in co-government models, urban interventions and cultural initiatives and counts to date 391 realised projects in Lisbon.

Despite the increasing experimentation on participatory policies and governance, several researchers identify the deficiency of an evaluation mechanism for their effectiveness as the greatest challenge and -possibly- need in order to highlight good practices and trajectories. The plurality in goals, methodologies and definitions of each case complicates the essay in developing replicable models of evaluation.

After ten years of implementation the BIP/ZIP strategy can become a lighthouse for knowledge-sharing for other cities. A comprehensive research on the program’s collaborative, operational and funding tools, together with a taxonomy of participatory governance projects internationally and a review on the published empirical evaluation literature is formative to identify indicators and key vocabulary for a transferable model of evaluation and co-governance. Therefore, the purpose of this project is to identify patterns and indicators and further experiment through community-based participatory research, in order to develop an evaluation toolkit integrated into a co-governance model.

The results of the research will contribute to the scientific discussion on participation evaluation, as well as to the design of a co-governance model. Starting with BIP/ZIP and Lisbon Municipality and communities, the model will offer itself as a tool for collaborative local development and co-management of the urban commons, contributing to a social-inclusive, sustainable future.

Instances of commoning in New York; or else a toilet, a fridge, and a shelf

Posted on 14-05-2024

Conferences

Read more ->

Exploring the Panorama of Barcelona's Urban Commons and the Dynamic State Relationships

Posted on 22-01-2024

Secondments

Read more ->

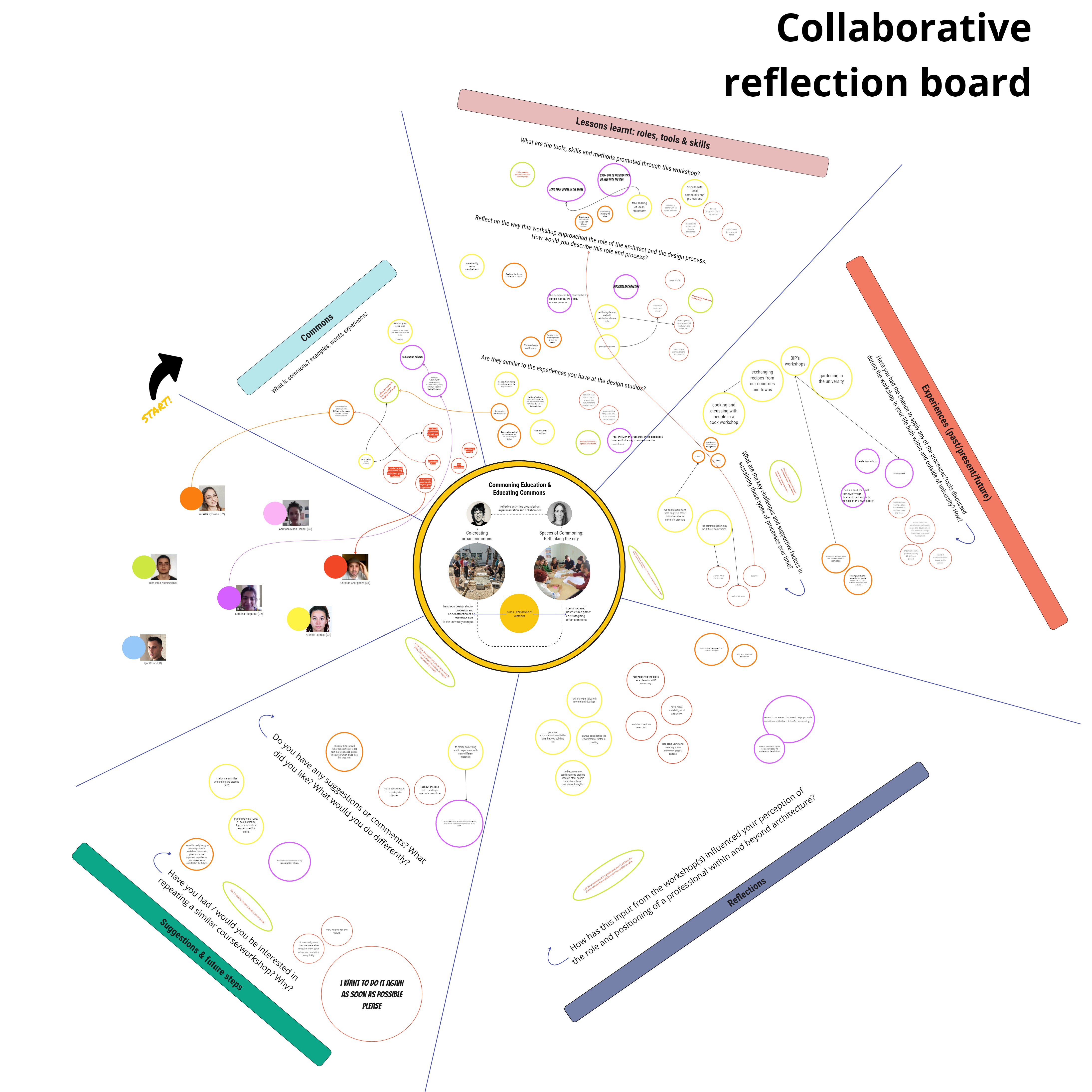

Architectural education as commons: Smooth Conference

Posted on 07-06-2023

Conferences

Read more ->

Participatory budgets and Sustainable Development Goals

Posted on 29-10-2022

Secondments

Read more ->

The wave of participation: bottom-up and top-down

Posted on 28-07-2022

Conferences, Reflections, Workshops

Read more ->

Threshold

Posted on 18-07-2021

Workshops

Read more ->

LiLa4Green

Created on 04-07-2023

Navarinou Park

Created on 03-10-2023

Lleialtat Santsenca Civic Centre

Created on 18-10-2024

Participatory Approaches

Placemaking

Public-civic Partnership

Social Infrastructure

Transdisciplinarity

Urban Commons

Urban Informality

Area: Community participation

Created on 17-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 24-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 30-07-2021

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 14-10-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Pappa, A., Tzika, Z., Roussou, E., & Panagidis, A. (2023, December). Informality as evidence: ethnographic insights from Southern European contexts. In KAEBUP 2023 Conference, Nicosia, Cyprus.

Posted on 21-12-2025

Conference

Read more ->Pappa, A., & Paio, A. (2023, October). The role of commons-oriented policies in the transformation of urban governance: The case of the participatory budget BIP/ZIP in Lisbon [Poster Presentation]. In 2nd Conference on Participatory Design. Transforming the City: Public Space & Environment, Inequalities & Democracy. Athens, Greece.

Posted on 21-12-2025

Conference

Read more ->