ISHF 2023: “At the end of the day, we are all here for the same reason. And we have to look out for each other”

Posted on 16-06-2023

Last week marked the fourth edition of the International Social Housing Festival (ISHF) and unlike last year in Helsinki, I didn’t spend the entire week in my hotel room with coronavirus. HURRAH! In fact, I was able to sleep in my own bed, because this year the festival came to my current hometown, Barcelona.

More than 1,800 international social and affordable housing providers, policymakers, city representatives, urbanists, architects, researchers, NGOs, and activists celebrated social housing over three days of activities: seminars, lectures, workshops, exhibitions, and site visits.

I was fortunate to help facilitate transfer of knowledge through seminar, exhibition, workshop, and live blogging, in collaboration with multiple social housing actors: RE-DWELL (academic), where I am an Early Stage Researcher; Housing Europe (European Federation), my current secondment in Brussels; and the Agència de l'Habitatge de Catalunya AHC (Regional Government Organisation), my previous collaborator on the HOUSEFUL project.

Read on to find out more.

RE-DWELL | Exhibition and Seminar

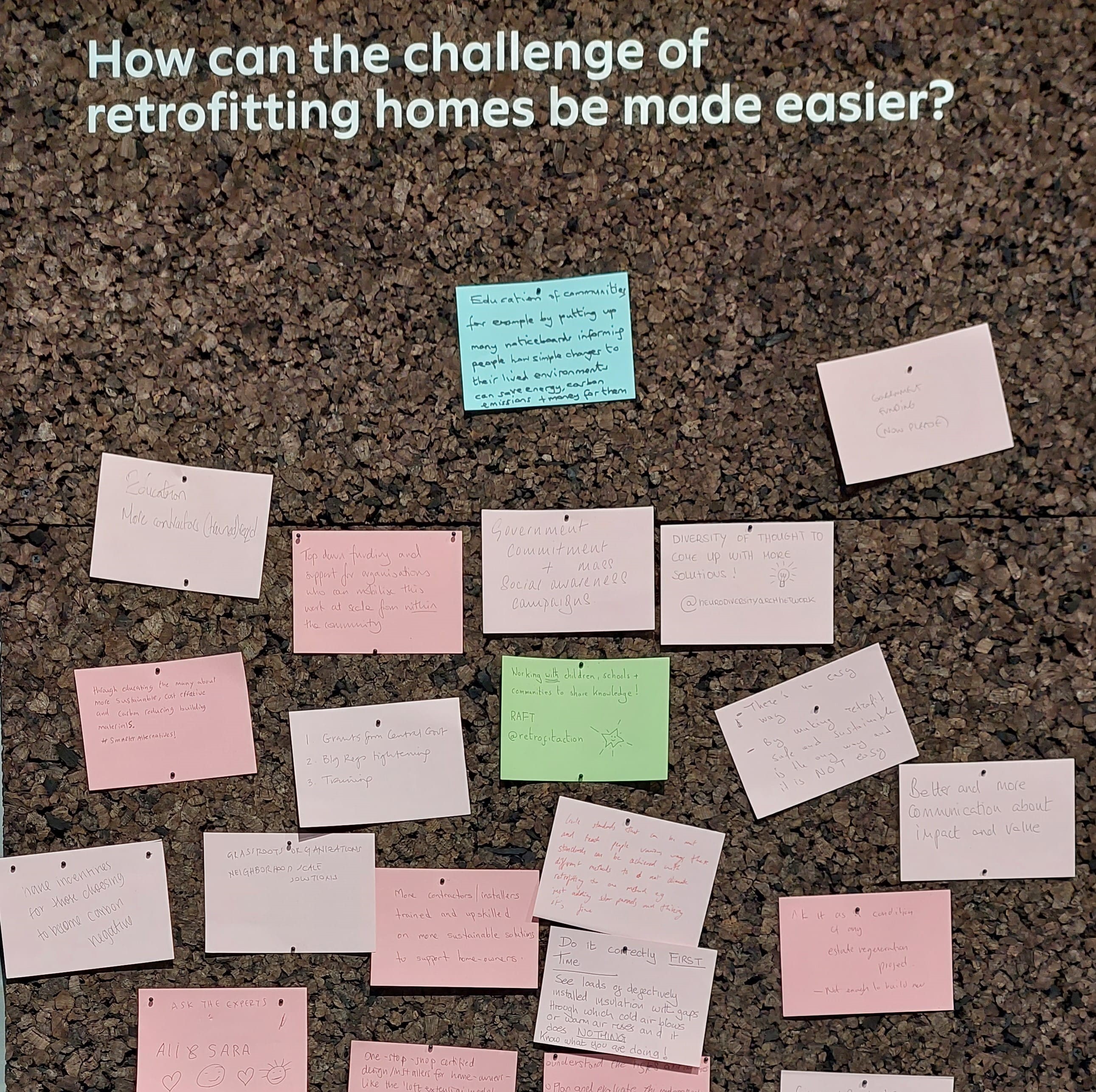

RE-DWELL designed and facilitated a participatory workshop in Helsinki, regarding our network’s three key research areas: Design, Planning, & Building; Community Participation; and Policy & Finance. RE-DWELL expanded with two key contributions in Barcelona: an exhibition of network-wide output – vocabulary entries and case study analyses; and a collaborative seminar with Housing Europe titled “Mass renovation of Affordable Housing: Industrial and Social Innovations”, investigating how social policies align with environmental policies and whether environmental housing policies are socially just, or bring tenants further burdens. Key takeaways include: we must retrofit en masse, industrialise the renovation process, avoid creating segregation, deploy organisational transformations to allow social innovation to emerge, value design by employing architects, and ensure socially just quality of life improvements.

The challenge is to consider behaviour to reduce the rebound effect and increase quality of the works and supply chain. Industrialisation could help, but for residents, CO2 reduction is a co-benefit to retrofit. The main benefits and desires are improved quality of life, summer comfort, vegetation, and new local business.

Housing Europe & AHC | Retrofit Workshop

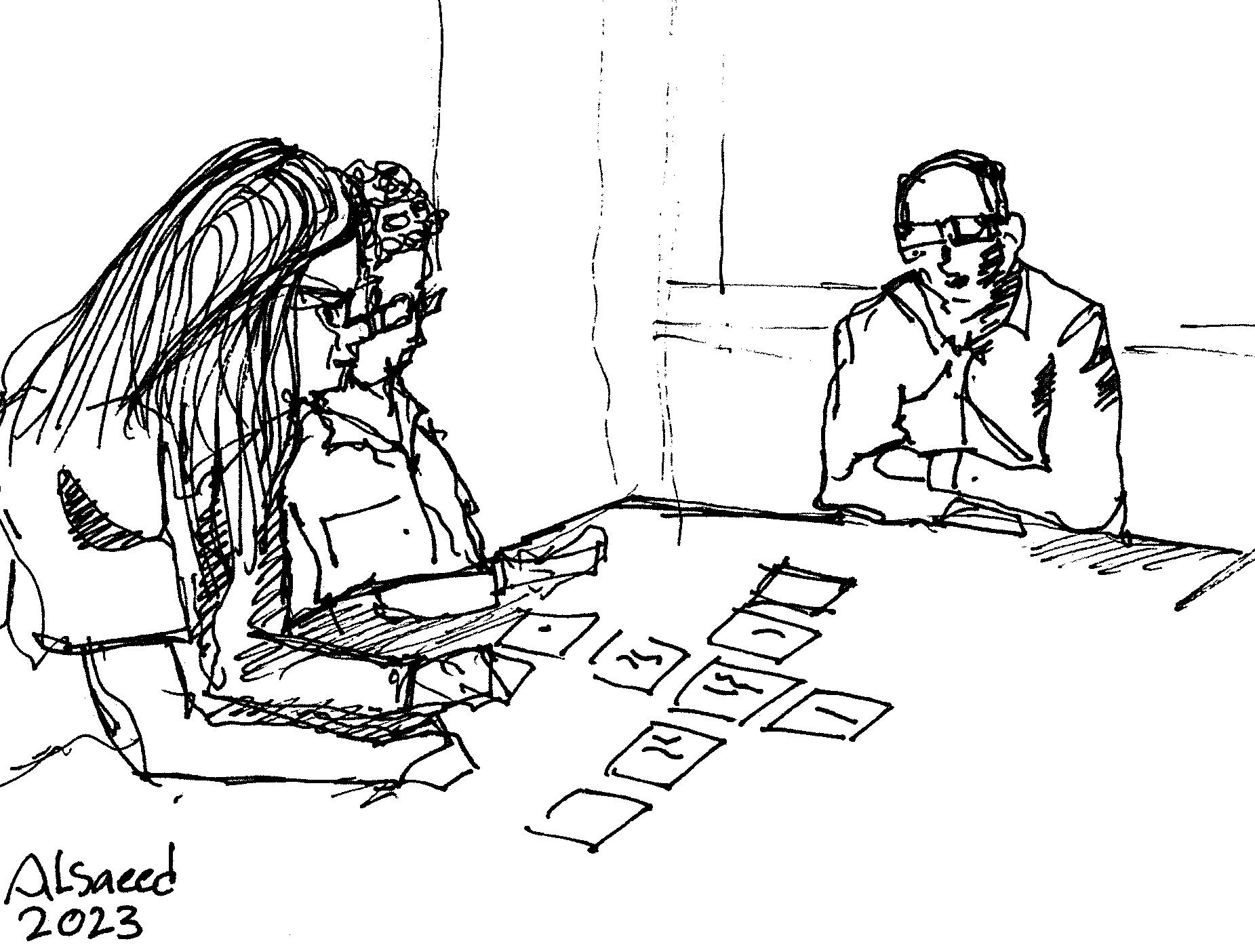

My secondment at Housing Europe enabled my involvement in “Resident Engagement Practices in Energy Efficient Social Housing”. The event began with presentations exploring sustainable projects: positive energy neighbourhood Syn.ikia EU by Incasòl, which I was fortunate to visit in Santa Coloma De Gramanet; and retrofit projects Green Deal ARV by Ajuntament De Palma and HOUSEFUL, 4RinEU, PLUG-N-HARVEST, and RELS by AHC. I then facilitated a workshop using a game of cards to explore different methodologies and tools to engage marginalised tenants in the retrofit process*.

Some results from the discussion:

ENGAGEMENT

Engagement should occur at the beginning of a project to give tenants options. When occurring at the end of the project, it’s hard to engage people. Tenant engagement should be factored into the programme at every stage of the project.

Tenants with little time and money are more difficult to engage. For example, elderly and very low-income residents. Children and parents are easier to engage, however, and we can offer incentives such as childcare and food.

METHODS OF PARTICIPATION

Overall, the most useful methods chosen in the workshop were sensory and/or tactile. Videos showcasing previous retrofit projects helps engagement, encouraging groups to come, join, and share the experience before facilitating a discussion. A demonstration house where people can attend and interact with the architects and products can be used – but only if designs are finalised. Expectations must be managed if it is subject to change.

A challenge to consider: Is there room for a demo-house as a decision-making tool?

TIMING AND TRANSPARENCY

Timing is a typical problem for housing associations. Everything should be discussed with all stakeholders to ensure everyone is on board and minimise time delays. If delays occur, transparency and honesty are key to cultivating trust – tenant updates should occur throughout the process.

LONG TERM

Tenant partnerships with construction projects are a great way to increase sense of ownership, upskill, and create jobs.

Housing Europe | Blog

Throughout the event, I was live blogging for the Housing Europe website, alongside four colleagues. This was a fantastic way to stay consistently engaged and distil the most important aspects of the events I visited – despite the cramp in my hand from typing so fast!

1. THE CARDBOARD FACTORY, FÁBRICA DE CARTRÒ BY INCASÒL

Fàbrica de Cartró, an old cardboard factory in Sant Joan Despí, Catalonia, is being investigated for retrofit and reuse by Incasòl. The aim is to create mixed-tenure housing, with a focus on sustainability, including social rental housing, affordable rental housing, cooperative spaces, and private ownership, considering the local community's participation. Desired features include prefabricated systems, renewable energies, a new public space linked to the river, increased dwellings, and common spaces for social value. Incasòl is exploring a public-private partnership model for a long-term lease, ensuring sustainability standards.

The retrofit will be a long journey. The structure needs improving to hold more storeys, the basement needs reinforcement. But the space is ethereal, and the façade is beautiful; it could always be removed and reused – an idea already under investigation.

Who will win? Retrofit, circularity, or demolition? We'll have to wait and see.

2. RENT CONTROL, RENT CONTROL!

The war in Ukraine has led to a 30% increase in construction costs, exacerbating the housing crisis amid growing urban migration. Insufficient housing supply results in vulnerable individuals living in subpar accommodations. The head of the EU office of the International Union of Tenants, Barbara Steenbergen calls for rent regulation and caps, while cautioning against landlords exploiting furnished apartments to evade rent control laws.

3. HOW FINLAND AVOIDS EVICTION

In 2002, a house fire caused by five people addicted to drugs prompted Finland to establish a proactive service aimed at preventing crises before they occur. Instead of relying on treatment, focus shifted to prevention. Housing Advisors, available to all residents regardless of tenure, offer housing advice to avoid evictions and serve as intermediaries between residents and social services. This approach helps individuals facing issues such as gambling addiction retain their homes and access the appropriate support services. Finland's high salaries and robust public social services do give it advantages over other states. But, consider this, the cost of a single eviction for housing companies is €10,600. Saving three people from eviction, therefore, covers the salary of one Housing Advisor.

Simple, yet effective.

4. ISHF TALKS ON PARTICIPATION, POLICY, RETROFIT, AND ENGAGEMENT

Montserrat Pareja, a housing researcher from the University of Barcelona, facilitated quick fire presentations of innovative academic research on social housing, covering topics such as tenant participation, policy, retrofitting, and engagement.

I end by quoting an insightful social housing tenant in the documentary about their new home: Casa Bloc: Rehabilitació d’una idea’ (Casa Bloc: Retrofit of an idea) – “At the end of the day, we are all here for the same reason. And we have to look out for each other”.

*Game cards were based on the results of an investigation into people-centred energy renovation processes by Broers et al. (2022).

References and Further Reading

The full Housing Europe live blog can be found here.

Read more about the documentary Casa Bloc: Rehabilitaciód'una idea

Broers, W., Kemp, R., Vasseur, V., Abujidi, N., & Vroon, Z. (2022). Justice in social housing: Towards a people-centred energy renovation process. Energy Research and Social Science, 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102527

Author:

S.Furman

(ESR2)