Retrofit and Social Engagement | We can do better

Posted on 13-07-2023

That’s it. The final summer school of RE-DWELL has officially been and gone. This year saw input not only from my cohort of ESRs and supervisors, but we were joined by industry partners to test the first iteration of RE-DWELL’s ‘Serious Game’ – which will be coming to a city near you. ‘Serious Game’ combines academia and industry to help all housing stakeholders navigate complex questions regarding holistically sustainable housing. Through the game, transdisciplinary discussion prompts action through tools and methods within policy and finance; design, planning and building; and community participation – the benchmark of RE-DWELLS investigations. This output will form a part of the transdisciplinary framework based on the ESR’s PhD’s.

One turn of the 'Serious Game' took our group from the solution “new tools to tailor make housing solutions”—through exploring methods including urban rooms, workshops with critical action research, transdisciplinary collaboration, and grant of use models—to answer: “could the participation of people living in social housing improve retrofit solutions more than end point performance targeted retrofit?” Funnily enough, this question is identical to one of my research questions.

Working on my PhD in social housing retrofit with tenant engagement, has put the terms “retrofit” and “social sustainability” on the tip of my tongue. Constantly ready to listen, learn, and discuss these concepts, I see blind spots everywhere. Tom Dollard from Pollard Thomas Edwards revealed a stunning environmentally sustainable scheme, even attempting some socially sustainable effort on the Blenheim Estate greenfield site in Oxfordshire but drew attention to the ethical grey area of building on a greenfield. Paul Quinn from Clarion revealed plans for regeneration that prioritise the Right-to-Return but is often not taken advantage of. A good way to keep the existing community together, Quinn says, is to build new environmentally sustainable housing on the same plot, decant the existing tenants into this housing, then retrofit the rest. Of course, this only works if the plot allows new buildings, and often buildings with retrofit potential are still cited for demolition and rebuild.

85-95% (European Commission, 2020) of buildings will remain standing in 2050, in the UK this extends to 80% of all dwellings (Pierpoint et al., n.d.) and they desperately need retrofitting for the climate crisis and for inhabitants. There are residential buildings in London designed for 40% occupancy. These leave 60% of those homes empty, acting as safety deposit boxes called “foreign investment”. Do we need to build more? Or do we need to re-enforce existing building stock and insist on full occupancy? When asked about retrofit, “we could do better” is a common reply from architects and housing associations. So why aren’t we doing better? It’s true that retrofit incurs more upfront cost that new build—in part because new build in the UK is exempt from tax, while retrofit is not—but the opportunities for long-term returns are enormous. To name a few: embodied carbon savings; new supply chains; opportunities to upskill unemployed tenants in a field with huge skills gaps; upskilling construction workers who fear a dwindling construction sector; physical and mental health and wellbeing implications; and integrative, iterative learning from the tenants who are experts in the way they live.

During the RE-DWELL visit to London, I visited the Building Centre exhibition Retrofit 23:Towards Deep Retrofit of Homes at Scale*. The exhibition (which I highly recommend) displays examples of retrofit from around the UK. The questions identified in the exhibition read “how do we fund retrofit and leverage the benefits? How best can deep retrofit be scaled up locally across streets and neighbourhoods to meet the net zero goals?”. It states that improving performance brings environmental, economic, and social benefits. Environmental benefits are easily displayed through energy performance statistics, economic benefits are displayed in terms of financial cost, but social benefits remain a struggle to translate beyond technical measures such as quantifiable indoor air quality and temperatures. The lack of quantifiable social benefits can be a huge barrier in tenant engagement because of the need to justify the extra expense, especially in social housing. But this is where engagement is most needed. In homes where residents are already disempowered by the knowledge that changes to their homes are not their decision to make. Noble efforts of community engagement displayed on a handful of case studies in the Retrofit 23 exhibition include: meetings with installers, on-site training, and one example of a resident design group where tenants had some real design impact.

Deep Retrofit comes with a specific restriction: to reduce energy consumption by 60-90% of pre-retrofit levels (Fawcett, 2014; Femenías et al., 2018) and therefore immediately places the focus on environmental sustainability and economic viability, consequently deemphasising social sustainability. So I ask the question: can deep retrofit lead to holistic sustainability? Mostly, engagement efforts are systems motivated, attempting to teach residents the correct use of technical systems, at times nominating technical agents from within the building to help transfer this knowledge to the others.

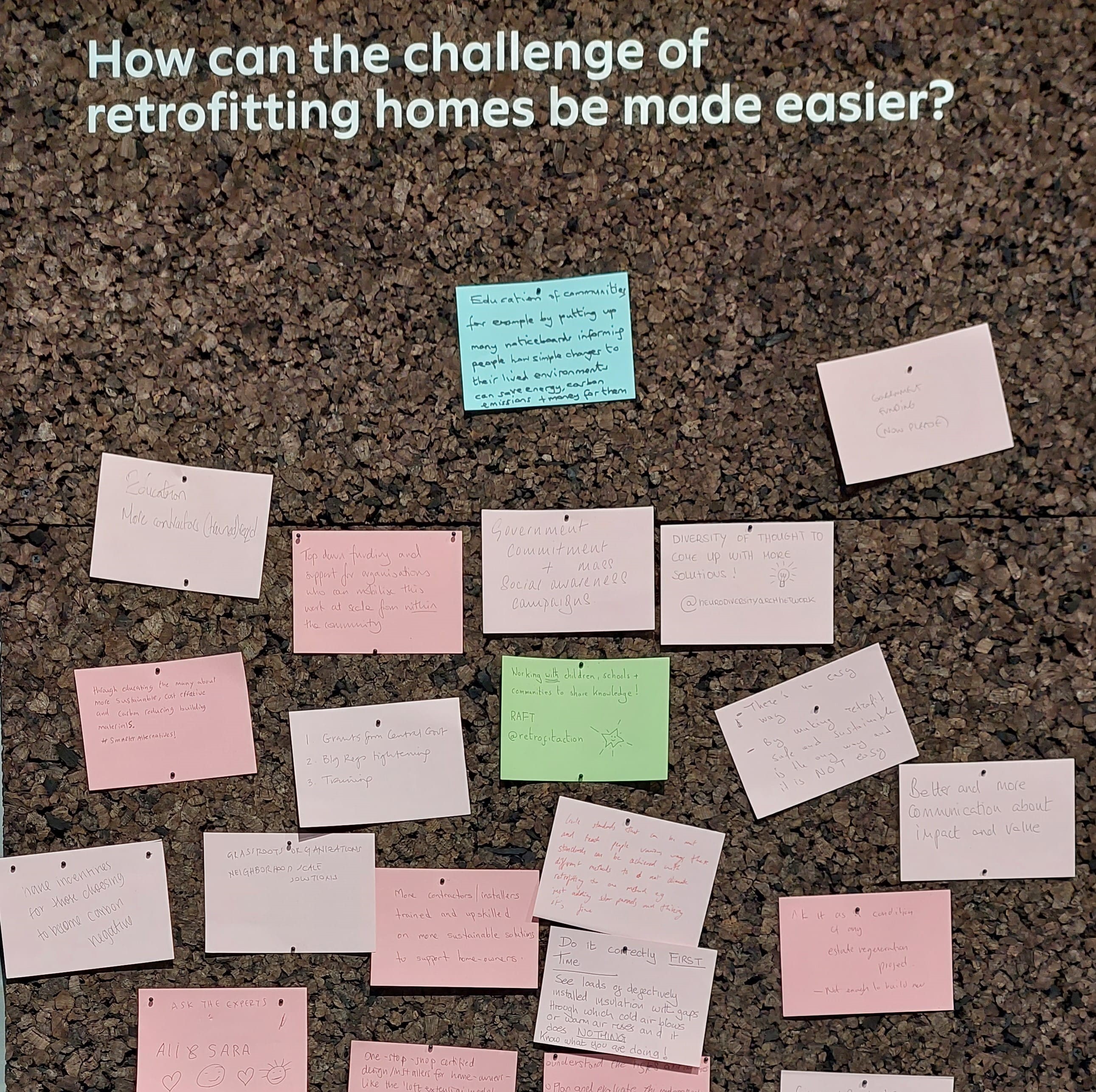

The biggest success of the Retrofit 23 exhibition must be the message board. Full of answers to the question “how can the challenge of retrofitting homes be made easier?”. Answers included: more grant money; increased low-carbon incentives; neighbourhood scale solutions; increase supply chains; increased education and training; upskill; knowledge sharing with children, schools, and communities; and attention to detail to avoid costly mistakes. My personal additions included cut tax on retrofit, extend funding spending deadlines, and legislate social engagement processes.

Often, social housing residents don’t want costly mechanical interventions, they want people to listen to their input and learn from the way they occupy their homes. Not that technical solutions don’t have their place, of course. But there are plenty of energy savings to be had with passive solutions, education, and conversation.

Let’s do better.

*Retrofit 23: Towards Deep Retrofit of Homes at Scale is a free exhibition held at the Building Centre in London until 29thSeptember 2023.

References

European Commission. (2020). A Renovation Wave for Europe -greening our buildings, creating jobs, improving lives.

Fawcett, T. (2014). Exploring the time dimension of low carbon retrofit: Owner-occupied housing. Building Research and Information, 42(4), 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2013.804769

Femenías, P., Mjörnell, K., & Thuvander, L. (2018). Rethinking deep renovation: The perspective of rental housing in Sweden. Journal of Cleaner Production, 195, 1457–1467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.282

Pierpoint, D., Rickaby, P., & Hancox, S. (n.d.). Social Housing Retrofit Toolkit MODULE 3: Housing Retrofit Policy Summary.

Related cases

Pre-1919 Niddrie Road Retrofit – An Example of Care for Climate and Health

Created on 15-11-2024

The Sutton Estate Regeneration, Chelsea

Created on 25-10-2024