Diagoon Houses

Created on 11-11-2022

The act of housing

The development of a space-time relationship was a revolution during the Modern Movement. How to incorporate the time variable into architecture became a fundamental matter throughout the twentieth century and became the focus of the Team 10’s research and practice. Following this concern, Herman Hertzberger tried to adapt to the change and growth of architecture by incorporating spatial polyvalency in his projects. During the post-war period, and as response to the fast and homogeneous urbanization developed using mass production technologies, John Habraken published “The three R’s for Housing” (1966) and “Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing” (1961). He supported the idea that a dwelling should be an act as opposed to a product, and that the architect’s role should be to deliver a system through which the users could accommodate their ways of living. This means allowing personal expression in the way of inhabiting the space within the limits created by the building system. To do this, Habraken proposed differentiating between 2 spheres of control: the support which would represent all the communal decisions about housing, and the infill that would represent the individual decisions. The Diagoon Houses, built between 1967 and 1971, follow this warped and weft idea, where the warp establishes the main order of the fabric in such a way that then contrasts with the weft, giving each other meaning and purpose.

A flexible housing approach

Opposed to the standardization of mass-produced housing based on stereotypical patterns of life which cannot accommodate heterogeneous groups to models in which the form follows the function and the possibility of change is not considered, Hertzberger’s initial argument was that the design of a house should not constrain the form that a user inhabits the space, but it should allow for a set of different possibilities throughout time in an optimal way. He believed that what matters in the form is its intrinsic capability and potential as a vehicle of significance, allowing the user to create its own interpretations of the space. On the same line of thought, during their talk “Signs of Occupancy” (1979) in London, Alison and Peter Smithson highlighted the importance of creating spaces that can accommodate a variety of uses, allowing the user to discover and occupy the places that would best suit their different activities, based on patterns of light, seasons and other environmental conditions. They argued that what should stand out from a dwelling should be the style of its inhabitants, as opposed to the style of the architect. User participation has become one of the biggest achievements of social architecture, it is an approach by which many universal norms can be left aside to introduce the diversity of individuals and the aspirations of a plural society.

The Diagoon Houses, also known as the experimental carcase houses, were delivered as incomplete dwellings, an unfinished framework in which the users could define the location of the living room, bedroom, study, play, relaxing, dining etc., and adjust or enlarge the house if the composition of the family changed over time. The aim was to replace the widely spread collective labels of living patterns and allow a personal interpretation of communal life instead. This concept of delivering an unfinished product and allowing the user to complete it as a way to approach affordability has been further developed in research and practice as for example in the Incremental Housing of Alejandro Aravena.

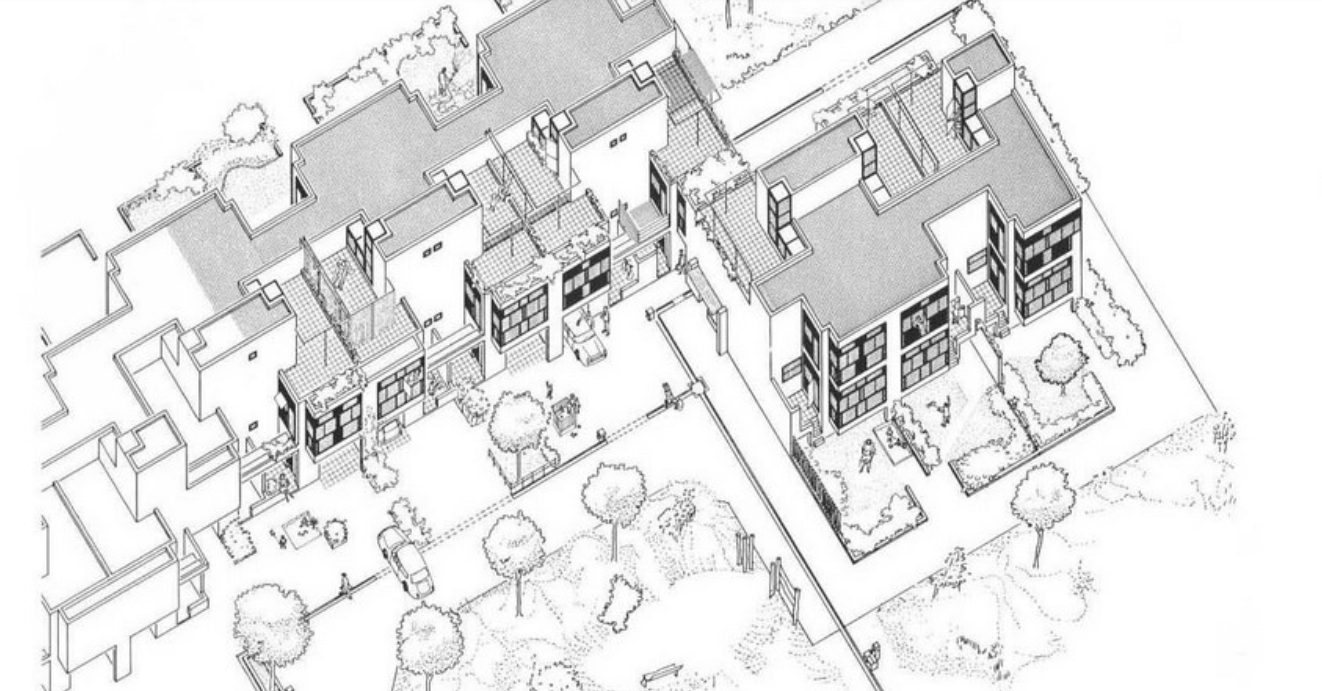

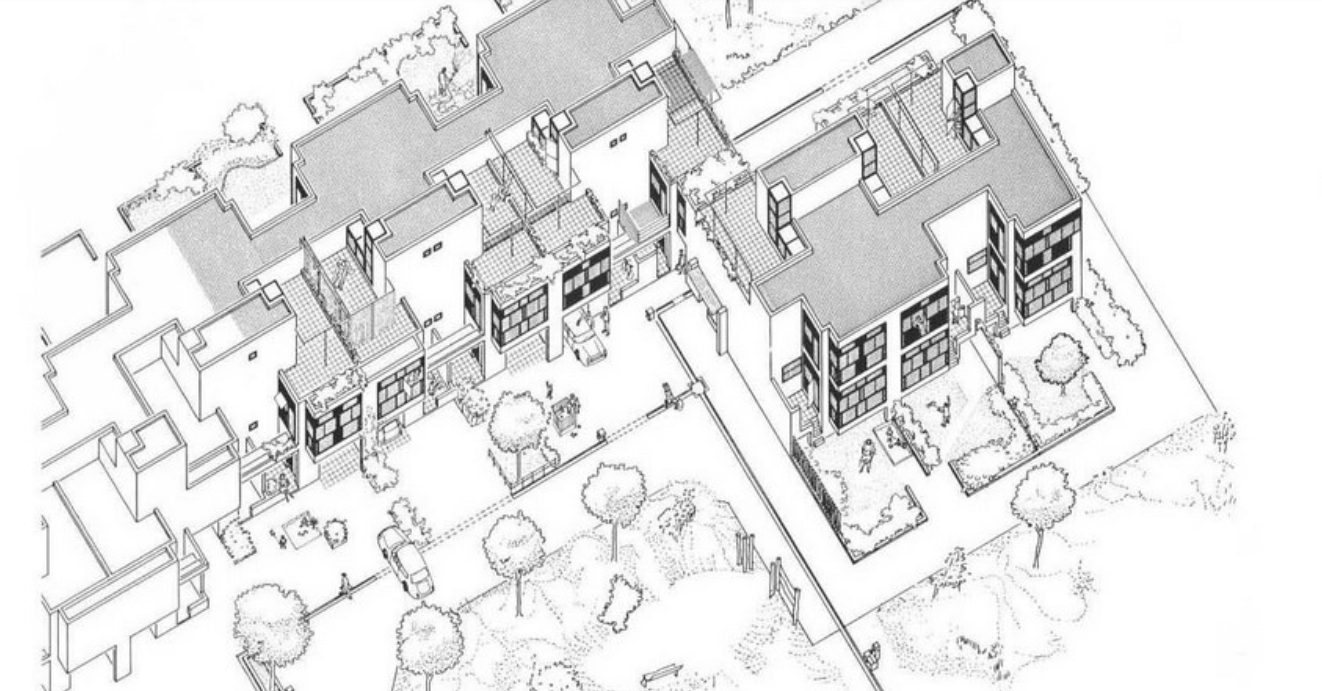

Construction characteristics

The Diagoon Houses consist of two intertwined volumes with two cores containing the staircase, toilet, kitchen and bathroom. The fact that the floors in each volume are separated only by half a storey creates a spatial articulation between the living units that allows for many optimal solutions. Hertzberger develops the support responding to the collective patterns of life, which are primary necessities to every human being. This enables the living units at each half floor to take on any function, given that the primary needs are covered by the main support. He demonstrates how the internal arrangements can be adapted to the inhabitants’ individual interpretations of the space by providing some potential distributions. Each living unit can incorporate an internal partition, leaving an interior balcony looking into the central living hall that runs the full height of the house, lighting up the space through a rooflight.

The construction system proposed by Herztberger is a combination of in-situ and mass-produced elements, maximising the use of prefabricated concrete blocks for the vertical elements to allow future modifications or additions. The Diagoon facades were designed as a framework that could easily incorporate different prefabricated infill panels that, previously selected to comply with the set regulations, would always result in a consistent façade composition. This allowance for variation at a minimal cost due to the use of prefabricated components and the design of open structures, sets the foundations of the mass customization paradigm.

User participation

While the internal interventions allow the users to covert the house to fit their individual needs, the external elements of the facade and garden could also be adapted, however in this case inhabitants must reach a mutual decision with the rest of the neighbours, reinforcing the dependency of people on one another and creating sense of community. The Diagoon Houses prove that true value of participation lies in the effects it creates in its participants. The same living spaces when seen from different eyes at different situations, resulted in unique arrangements and acquired different significance. User participation creates the emotional involvement of the inhabitant with the environment, the more the inhabitants adapt the space to their needs, the more they will be inclined to lavish care and value the things around them. In this case, the individual identity of each household lied in their unique way of interpreting a specific function, that depended on multiple factors as the place, time or circumstances. While some users felt that the house should be completed and subdivided to separate the living units, others thought that the visual connections between these spaces would reflect better their living patterns and playful arrangement between uses.

After inhabiting the house for several decades, the inhabitants of the Diagoon Houses were interviewed and all of them agreed that the house suggested the exploration of different distributions, experiencing it as “captivating, playful and challenging”1. There was general approval of the characteristic spatial and visual connection between the living units, although some users had placed internal partitions in order to achieve acoustic independence between rooms. One of the families that had been living there for more than 40 years indicated that they had made full use of the adaptability of space; the house had been subject to the changing needs of being a couple with two children, to present when the couple had already retired, and the children had left home. Another of the families that was interviewed had changed the stereotypical room naming based on functions (living room, office, dining room etc.) for floor levels (1-4), this could as well be considered a success from Hertzberger as it’s a way of liberating the space from permanent functions. Finally, there were divergent opinions with regards to the housing finishing, some thought that the house should be fitted-out, while others believed that it looked better if it was not conventionally perfect. This ability to integrate different possibilities has proven that Hertzberger’s experimental houses was a success, enhancing inclusivity and social cohesion. Despite fitting-out the inside of their homes, the exterior appearance has remained unchanged; neighbourly consideration and community identity have been realised in the design. The changes reflecting the individual identity do not disrupt the reading of the collective housing as a whole.

Spatial polivalency in contemporary housing

From a contemporary point of view, in which a housing project must be sustainable from an environmental, social and economic perspective, the strategies used for the Diagoon Houses could address some of the challenges of our time. A recent example of this would be the 85 social housing units in Cornellà by Peris+Toral Arquitectes, which exemplify how by designing polyvalent and non-hierarchical spaces and fixed wet areas, the support system has been able to accommodate different ways of appropriation by the users, embracing social sustainability and allowing future adaptations. As in Diagoon, in this new housing development the use of standardized, reusable, prefabricated elements have contributed to increasing the affordability and sustainability of the dwellings. Additionally, the use of wood as main material in the Cornellà dwellings has proved to have significant benefits for the building’s environmental impact. Nevertheless, while this matrix of equal room sizes, non-existing corridors and a centralised open kitchen has been acknowledged to avoid gender roles, some users have criticised the 13m² room size to be too restrictive for certain furniture distributions.

All in all, both the Diagoon houses and the Cornellà dwellings demonstrate that the meaning of architecture must be subject to how it contributes to improving the changing living conditions of society. Although different in terms of period, construction technologies and housing typology, these two residential buildings show strategies that allow for a reinterpretation of the domestic space, responding to the current needs of society.

C.Martín. ESR14

Read more

->

La Borda

Created on 16-10-2024

The housing crisis

After the crisis of 2008, it became obvious that the mainstream mechanisms for the provision of housing were failing to provide secure and affordable housing for many households, especially in the countries of the European south such as Spain. It is in this context that alternative forms emerged through social initiatives. La Borda is understood as an alternative form of housing provision and a tenancy form in the historical and geographical context of Catalonia. It follows mechanisms for the provision of housing that differ from predominant approaches, which have traditionally been the free market, with a for-profit and speculative role, and a very low percentage of public provision (Allen, 2006). It also constitutes a different tenure model, based on collective instead of private ownership, which is the prevailing form in southern Europe. As such, it encompasses the notions of community engagement, self-management, co-production and democratic decision-making at the core of the project.

Alternative forms of housing

In the context of Catalonia, housing cooperatives go back to the 1960s when they were promoted by the labour movement or by religious entities. During this period, housing cooperatives were mainly focused on promoting housing development, whether as private housing developers for their members or by facilitating the development of government-protected housing. In most cases, these cooperatives were dissolved once the promotion period ended, and the homes were sold.

Some of these still exist today, such as the “Cooperativa Obrera de Viviendas” in El Prat de Llobregat. However, this model of cooperativism is significantly different from the model of “grant of use”, as it was used mostly as an organizational form, with limited or non-existent involvement of the cooperative members.

It was only after the 2008 crisis, that new initiatives have arisen, that are linked to the grant-of-use model, such as co-housing or “masoveria urbana”. The cooperative model of grant-of-use means that all residents are members of the cooperative, which owns the building. As members, they are the ones to make decisions about how it operates, including organisational, communitarian, legislative, and economic issues as well as issues concerning the building and its use. The fact that the members are not owners offers protection and provides for non-speculative development, while actions such as sub-letting or transfer of use are not possible. In the case that someone decides to leave, the flat returns to the cooperative which then decides on the new resident. This is a model that promotes long-term affordability as it prevents housing from being privatized using a condominium scheme. The grant -of -use model has a strong element of community participation, which is not always found in the other two models. International experiences were used as reference points, such as the Andel model from Denmark and the FUCVAM from Uruguay, according to the group (La Borda, 2020). However, Parés et al. (2021) believe that it is closer to the Almen model from Scandinavia, which implies collective ownership and rental, while the Andel is a co-ownership model, where the majority of its apartments have been sold to its user, thus going again back to the free-market stock.

In 2015, the city of Barcelona reached an agreement with La Borda and Princesa 49, allowing them to become the first two pilot projects to be constructed on public land with a 75-year leasehold. However, pioneering initiatives like Cal Cases (2004) and La Muralleta (1999) were launched earlier, even though they were located in peri-urban areas. The main difference is that in these cases the land was purchased by the cooperative, as there was no such legal framework at the time. This means that these projects are classified as Officially Protected Housing (Vivienda de Protección Oficial or VPO), and thus all the residents must comply with the criteria to be eligible for social housing, such as having a maximum income and not owning property. Also, since it is characterised as VPO there is a ceiling to the monthly fee to be charged for the use of the housing unit, thus keeping the housing accessible to groups with lower economic power. This makes this scheme a way to provide social housing with the active participation of the community, keeping the property public in the long term. After the agreed period, the plot will return to the municipality, or a new agreement should be signed with the cooperative.

The neighbourhood movement

In 2011, a group of neighbours occupied one of the abandoned industrial buildings in the old industrial state of Can Batlló in response to an urban renewal project, with the intention of preserving the site's memory (Can Batlló, 2020; Girbés-Peco et al., 2020). The neighbourhood movement known as "Recuperem Can Batlló" sought to explore alternative solutions to the housing crisis of the time. The project started in 2012, after a series of informal meetings with an initial group of 15 people who were already active in the neighbourhood, including members of the architectural cooperative Lacol, members of the labour cooperative La Ciutat Invisible, members of the association Sostre Civic and people from local civic associations. After a long process of public participation, where the potential uses of the site were discussed, they decided to begin a self-managed and self-promotion process to create La Borda. In 2014 they legally formed a residents’ cooperative and after a long process of negotiation with the city council, they obtained a lease for the use of the land for 75 years in exchange for an annual fee. At that time, the group expanded, and it went from 15 members to 45. After another two years of work, construction started in 2017 and the first residents moved in the following year.

The participatory process

The word “participation” is sometimes used as a buzzword, where it refers to processes of consultation or manipulation of participants to legitimise decisions, leading it to become an empty signifier. However, by identifying the hierarchies that such processes entail, we can identify higher levels of participation, that are based on horizontality, reciprocity, and mutual respect. In such processes, participants not only have equal status in decision-making, but are also able to take control and self-manage the whole process. This was the case with La Borda, a project that followed a democratic participation process, self-development, and self-management. An important element was also the transdisciplinary collaboration between the neighbours, the architects, the support entities and the professionals from the social economy sector who shared similar ideals and values.

According to Avilla-Royo et al. (2021), greater involvement and agency of dwellers throughout the lifetime of a project is a key characteristic of the cooperative housing movement in Barcelona. In that way, the group collectively discussed, imagined, and developed the housing environment that best covered their needs in typological, material, economic or managerial terms. The group of 45 people was divided into different working committees to discuss the diverse topics that were part of the housing scheme: architecture, cohabitation, economic model, legal policies, communication, and internal management. These committees formed the basis for a decision-making assembly. The committees would adapt to new needs as they arose throughout the process, for example, the “architectural” committee which was responsible for the building development, was converted into a “maintenance and self-building” committee once the building was inhabited. Apart from the specific committees, the general assembly is the place, where all the subgroups present and discuss their work. All adult members have to be part of a committee and meet every two weeks. The members’ involvement in the co-creation and management of the cooperative significantly reduced the costs and helped to create the social cohesion needed for such a project to succeed.

The building

After a series of workshops and discussions, the cooperative group together with architects and the rest of the team presented their conclusions on the needs of the dwellers and on the distribution of the private and communal spaces. A general strategy was to remove areas and functions from the private apartments and create bigger community spaces that could be enjoyed by everyone. As a result, 280 m2 of the total 2,950 m2 have been allocated for communal spaces, accounting for 10% of the entire built area. These spaces are placed around a central courtyard and include a community kitchen and dining room, a multipurpose room, a laundry room, a co-working space, two guest rooms, shared terraces, a small community garden, storage rooms, and bicycle parking. La Borda comprises 28 dwellings that are available in three different typologies of 40, 50 and 76 m2, catering to the needs of diverse households, including single adults, adult cohabitation, families, and single parents. The modular structure and grid system used in the construction of the dwellings offer the flexibility to modify their size in the future.

The construction of La Borda prioritized environmental sustainability and minimized embedded carbon. To achieve this, the foundation was laid as close to the surface as possible, with suspended flooring placed a meter above the ground to aid in insulation. Additionally, the building's structure utilized cross-laminated timber (CLT) from the second to the seventh floors, after the ground floor made of concrete. This choice of material had the advantage of being lightweight and low carbon. CLT was used for both the flooring and the foundation The construction prioritized the optimization of building solutions through the use of fewer materials to achieve the same purpose, while also incorporating recycled and recyclable materials and reusing waste. Furthermore, the cooperative used industrialized elements and applied waste management, separation, and monitoring. According to the members of the cooperative (LaCol, 2020b), an important element for minimizing the construction cost was the substitution of the underground parking, which was mandatory from the local legislation when you exceed a certain number of housing units, with overground parking for bicycles. La Borda was the first development that succeeded not only in being exempt from this legal requirement but also in convincing the municipality of Barcelona to change the legal framework so that new cooperative or social housing developments can obtain an “A” energy ranking without having to construct underground parking.

Energy performance goals focused on reducing energy demands through prioritizing passive strategies. This was pursued with the bioclimatic design of the building with the covered courtyard as an element that plays a central role, as it offers cross ventilation during the warm months and acts as a greenhouse during the cold months. Another passive strategy was enhanced insulation which exceeds the proposed regulation level. According to data that the cooperative published, the average energy consumption of electricity, DHW, and heating per square meter of La Borda’s dwellings is 20.25 kWh/m², which is 68% less, compared to a block of similar characteristics in the Mediterranean area, which is 62.61 kWh/m² (LaCol, 2020a). According to interviews with the residents, the building’s performance during the winter months is even better than what was predicted. Most of the apartments do not use the heating system, especially the ones that are facing south. However, the energy demands during the summer months are greater, as the passive cooling system is not very efficient due to the very high temperatures. Therefore, the group is now considering the installation of fans, air-conditioning, or an aerothermal installation that could provide a common solution for the whole building. Finally, the cooperative has recently installed solar panels to generate renewable energy.

Social impact and scalability

According to Cabré & Andrés (2018), La Borda was created in response to three contextual factors. Firstly, it was a reaction to the housing crisis which was particularly severe in Barcelona. Secondly, the emergence of cooperative movements focusing on affordable housing and social economies at that time drew attention to their importance in housing provision, both among citizens and policy-makers. Finally, the moment coincided with a strong neighbourhood movement around the urban renewal of the industrial site of Can Batlló. La Borda, as a bottom-up, self-initiated project, is not just an affordable housing cooperative but also an example of social innovation with multiple objectives beyond providing housing.

The group’s premise of a long-term leasehold was regarded as a novel way to tackle the housing crisis in Barcelona as well as a form of social innovation. The process that followed was innovative as the group had to co-create the project, which included the co-design and self-construction, the negotiation of the cession of land with the municipality, and the development of financial models for the project. Rather than being a niche project, the aim of La Borda is to promote integration with the neighbourhood. The creation of a committee to disseminate news and developments and the open days and lectures exemplify this mission. At the same time, they are actively aiming to scale up the model, offering support and knowledge to other groups. An example of this would be the two new cooperative housing projects set up by people that were on the waiting list for la Borda. Such actions lead to the creation of a strong network, where experiences and knowledge are shared, as well as resources.

The interest in alternative forms of access to housing has multiplied in recent years in Catalonia and as it is a relatively new phenomenon it is still in a process of experimentation. There are several support entities in the form of networks for the articulation of initiatives, intermediary organizations, or advisory platforms such as the cooperative Sostre Civic, the foundation La Dinamo, or initiatives such as the cooperative Ateneos, which were recently promoted by the government of Catalonia. These are also aimed at distributing knowledge and fostering a more inclusive and democratic cooperative housing movement. In the end, by fostering the community’s understanding of housing issues, and urban governance, and by seeking sustainable solutions, learning to resolve conflicts, negotiate and self-manage as well as developing mutual support networks and peer learning, these types of projects appear as both outcomes and as drivers of social transformation.

Z.Tzika. ESR10

Read more

->

The Elwood Project, Vancouver, Washington

Created on 25-01-2024

The Elwood Project is an affordable housing development and includes forty-six apartments and supportive housing services provided by Sea-Mar Community Services. All apartments are subsidised through the Vancouver Housing Authority, so that tenants pay thirty-five percent of their income towards rent, according to public housing designation. There are garden-style apartments to allow residents to choose when and where to interact with neighbours. Units are 37 sq. m. with 1 bedroom. These apartments are fully accessible and amenities include a community room, laundry room, covered bike parking, and outdoor courtyard with a community garden (Housing Initiative, 2022).

This case highlights the benefits of trauma informed design (TID) in the supportive housing sector. These homes were built using concepts of open corridors, natural light, art and nature, colours of nature, natural materials, design with commercial sustainability, elements of privacy and personalization, open areas, adequate and easy access to services. With these thoughtful techniques, Elwood offers socially sustainable help for vulnerable people (people with special needs, homeless, formally homeless) and for the new “housing precariat”.

The Elwood project is a good example of combining private apartments with opportunities for community living, where services and facilities management contribute to the well-being and stability of dwellers. What makes this project especially unique is that it does not look like affordable housing. As Brendan Sanchez concluded, people think that it “looks like really nice market rate upscale housing”, which is empowering, because people in general “deserve access to quality-built environment and healthy indoor interior environments”. Access Architecture did not design it as affordable housing, they just “designed it as housing” (Access Architecture, 2022).

Affordability aspects

The Elwood affordable housing community project is in a commercially zoned transit corridor. Existing planning regulations did not allow building permits in this area. Elwood is the first affordable housing development in the city of Vancouver that has required changes to the city’s zoning regulations. As a result of these changes, other measures have been adopted to promote affordable housing in the community. Under the city's previous building regulations, it was simply not possible to obtain a building permit. The Affordable Housing Fund helped developers to undertake this project and provided tenants with budget friendly housing options (Otak, 2022).

Now, thanks to the Elwood project, there are ongoing talks at the Board of the Planning Commission of Elwood Town to get construction permits for similar projects. As the council stated, “it is on the horizon for all towns to have affordable housing” (Elwood Town Corporation, 2022). Although the population of the area is small, it is estimated that in the coming years the need for more affordable housing units will increase. Previously, permitted uses were limited to C-2 (general commercial, office and retail) and C-3 (intensive service commercial) zoning uses (e.g., gas station, restaurant, public utility substation). Currently, the members of the town council together with other stakeholders are negotiating new plans for affordable housing in the area. With the help of the community, they are striving to harmonise the legal, political, financial and design aspects and work on a general plan that includes the construction of multi-family affordable dwellings. In addition, the ultimate goal is to further modify zoning regulations to incorporate tax advantages for social housing.

Sustainability aspects

It is a highly energy efficient building as it meets the minimum requirements of the Evergreen Sustainable Development Standards (ESDS), which include requirements for low Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) content, water conservation, air sealing, and reduction of thermal bridges. It also meets the Green Point Rated Program requirements. The building materials are bamboo, cork, salvaged or FSC-Certified wood, natural linoleum, natural rubber and ceramic tile. There are no VOC adhesives or synthetic backing in living rooms, and bathrooms (Otak, 2022).

Design

Access Architecture used an outcome-based design process during the development of this project.

The outcome-based design process considers TID principles to lower barriers among tenants and minimize stigma of receiving services. Brendan Sanchez from Access Architecture highlights that TID is a kind of design that is “getting a lot more attention now that people understand it more. It applies in this project, and we’re also just finding that it doesn’t have to be a certain traumatic event we design for. It can also be a systemic problem — we all have our own traumas we’re working through, especially after the events of the pandemic last year. So Access likes to focus on how we can create healing spaces in this kind of design.” (Nichiha, 2022)

As Di Raimo et al. (2021) wrote, trauma informed approaches can be adopted by a wide range of service providers (health, social care, education, justice). In this case, Sea Mar-Community Services Northwest’s Foundational Community Support provides guidance for tenants with the help of case managers. Such partners can help with professional and health objectives. CDM Caregiving Services helps (or offer assistance) with daily tasks from cooking to cleaning and hygiene. Finally, Vancouver Housing Authority members help with anything they can, so that tenants would not feel themselves alone with their problems (Nahro, 2022).

Elwood offers informal indoor and outdoor spaces which provide a relaxed atmosphere in a friendly milieu. In this building, TID suits the resident’s needs. The building was planned with the help of potential residents and social workers, so that a sense of space and place would provide familiarity, stability, and safety for those who are longing for the feeling of place attachment.

A.Martin. ESR7

Read more

->

Knight’s Walk (Lambeth's Homes)

Created on 26-07-2024

The review of this case study is structured to address aspects of architectural design, construction approach, and sustainability integration. The analysis draws on a range of data sources, including project design and access statements, sustainability statements, design drawings, planning applications, associated communications and archival records obtained from the planners, public records and the London Borough of Lambeth planning portal.

1. Design statement

The project site stretches to approximately 0.86 hectares, 84 residential units at a density of 215 dwellings per hectare are planned to be housed on the site. The surrounding areas are characterised by the prevalence of historic conservation areas. The site is located on the western side of the Cotton Garden Estate and is known for its public park and distinctive 22-storey Ebenezer, Hurley and Fairford towers. To the north is the Walcot Road Conservation Area with its three-storey terraced houses. To the east is Renfrew Roadside, which contains several listed buildings, including the Magistrates Court, the former Lambeth Fire Station and Workhouse (later converted to Lambeth Hospital) and what is now The Cinema Museum (Mae, 2017). Figure 1 illustrates the location of the project within the urban fabric of London.

In response to the unique characteristics and features of the site, the design team developed a comprehensive strategy to integrate the development. Firstly, the scale and massing have been carefully balanced in order to harmonize with the surrounding area. This is achieved through the use of graduated massing and a deliberate emphasis on the incorporation of open spaces and parks (Mae, 2017). Secondly, the existing transport and vehicular access has been maintained to avoid creating new routes. Thirdly, a car-free zone has been established, with the number of parking spaces on the site limited to eight, exclusively for residential units. Additionally, a number of bicycle parking bays have been installed to provide secure and convenient storage for cyclists. Fourthly, the "The Walk" concept has been implemented, offering a pedestrian route designed with human needs in mind, in an aim to promote connectivity between the site, parks, buildings, and existing public areas. This includes creating gateways and landmarks to enhance the sense of procession along the footpaths. Moreover, a balanced integration of soft and hard landscape elements was pursued to foster a sense of cohesive connectivity while preserving the site's architectural heritage (Mae, 2017). Figure 2 provides a comparative visual representation of the former site against the proposed design. Figure 2 provides a comparative visual representation of the former site against the proposed design for Knight’s Walk.

From a typological perspective, a total of 84 units have been developed, ranging in size from 54 square metres for the smallest units to 90 square metres for the largest. Phase one comprises 16 flats, including 10 one-bedroom flats, three two-bedroom flats and three three-bedroom flats. In contrast, phase two offers a broader choice with 15 one-bedroom flats, 38 two-bedroom flats and 15 three-bedroom flats.

With regard to architectural design, three key design considerations were identified as being of particular importance (HDA, 2022; Mae, 2017). The primary concern was the accessibility of the site for its residents, with particular attention paid to the needs of senior citizens and those with special requirements. This emphasis is particularly pronounced in Phase One, where the majority of units have been designed to meet both the Building Regulations Part M (which provides guidance on access to and use of buildings, including facilities for disabled occupants and easy movement through a building), and the prescribed national standards for accessible spaces (Mae, 2017). Secondly, the efficient use of space was prioritised, with the use of simple and clean architectural lines to optimise the functionality within each unit and the circulation areas. Thirdly, the well-being of residents was a significant consideration, with each unit featuring a terrace overlooking the surrounding green spaces and parks. The overall distribution of flats in both phases is shown in Figure 3.

2. Construction

In terms of construction methods, the project adopts a fabric-first approach that focuses on improving the properties of the building fabric, with the objective of optimising thermal performance, airtightness and moisture management. This approach is intended to reduce the necessity for additional mechanical or technical solutions, thereby achieving enhanced energy efficiency and comfort (Eyre et al., 2023). In addition, project planners have incorporated supplementary measures to improve construction processes (Mae, 2017). These include using a reinforced concrete structure in locations prone to thermal bridging, while avoiding cores as the primary structural support system. Furthermore, a strategy to rationalise the building’s "form factor" ensures a coherent visual progression of the building mass whilst mitigating thermal impacts such as overheating on the overall building envelope. Secondly, a balanced glazing ratio has been implemented to reduce direct thermal impacts, with the additional benefit of providing resistance to thermal mass. The use of light-coloured materials also serves to reduce the heat island effect and thermal conductivity between the exterior and interior of the building. Finally, the use of a cantilevered method, particularly in building extensions, reduces thermal bridging while improving the overall aesthetics of the structures.

3. Sustainability and energy

Several methods to promote sustainability have been integrated into the building’s envelope. The project follows the three-point model known as the "energy hierarchy", which is based on the principles of "Be Lean", "Be Clean", and "Be Green". “Be Lean” emphasizes the planning and construction of buildings that consume less energy. "Be Clean" focuses on efficiently providing and consuming energy, while "Be Green" aims to meet energy needs through renewable sources (Muralidharan, 2021).

3.1. Energy and carbon strategy

In line with energy hierarchy models, the project's energy strategy focuses on the building envelope and incorporates high-performance standards recommended by Passivhaus to optimise building mass and thermal boundaries. In addition, provisions have been made to future-proof the buildings by providing provisional spaces for future connection to planned district and central heating systems. Efforts to reduce carbon emissions centre on establishing accurate baseline emissions using the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP), implementing passive measures such as natural ventilation and high-efficiency appliances, and reducing reliance on fossil fuels for electricity generation through the use of photovoltaic cells as a secondary energy source. As a result, the buildings have achieved a 35 per cent reduction in carbon emissions compared to local regulations and similar developments (Mae, 2017; TGA, 2017).

3.2. Overheating strategy

Managing the risk of overheating has become an essential consideration in the design and construction of housing in the UK (Sameni et al., 2015). The quality of the indoor environment in any dwelling, particularly in summer, is vulnerable to excessive solar heat gain which is accentuated by the lack of rapid ventilation measures. To mitigate these challenges, the project's overheating strategy minimises internal heat generation through energy-efficient design and reduces heat gain through careful orientation, shading, windows, and insulation. Passive ventilation measures, such as natural cross-ventilation and fixed external shading, are also utilised. In addition, primary heating pipework is carefully planned to minimise losses, particularly when installed within the dwellings (TGA, 2017).

3.3. Policy and standards

The project has been developed in accordance with a complex network of interrelated policies and standards at the national, regional and local levels, in addition to mandatory national sustainability guidelines. Notably, Building Regulations Part L, which sets out specific requirements for insulation, heating systems, ventilation and fuel use, and aim to reduce carbon emissions by 31 per cent compared to those of previous regulations. Knight's Walk introduced a new layer of mandatory requirements, designated as "regional" guidelines. These guidelines are specific to the Greater London area and serve as a reference for all developments. In addition to fulfilling the national and regional regulations, the project had to comply with the requirements set forth by the local councils. Furthermore, the developer's requirements, known as Lambeth's Housing Design Standards function as a clarifying framework, outlining the pertinent policies at the national and regional levels.

As a result, the project has comfortably achieved an energy rating of B (based on the Standards Assessment Procedure calculations), with the potential to progress to an A rating. The project has developed a multi-level sustainability strategy and architectural language that considers climate, environment, and local needs, focusing on energy and carbon reduction. These strategies include encouraging active travel, increasing biodiversity and implementing adaptations to mitigate the effects of climate change through a drainage strategy and incorporating SuDS and tree planting. In addition, each flat has been fitted with mechanical ventilation with heat recovery, providing a constant supply of fresh, filtered air even when the windows are closed. All apartments are also equipped with energy-saving electrification systems to minimise electricity consumption (HDA, 2022).

4. Reflections

The section highlights both the successful aspects and the potential areas for improvement identified in the previous sections by addressing the following questions:

What methodologies were deployed within Knight’s Walk that can be classified as exemplifying ‘good’ practise?

The comprehensive assessments conducted by the designers, covering a wide range of intervention areas, facilitated the formulation of a responsible phasing strategy that mitigated the social, economic, and environmental risks associated with large-scale development projects. The early provision of alternative, well-built housing for tenants who were displaced has fostered robust collaboration between developers, designers, and local communities.

The project was developed in accordance with widely recognised accessibility standards, including compliance with Building Regulations Part M. A comprehensive assessment framework was employed to measure the quality of outcomes in line with national, regional, and local policies. In order to facilitate the adoption of improved energy efficiency strategies, consultation was undertaken with specialists versed in Passivhaus design standards. As a result of this consultation, it was determined that no additional standards were required. These strategies included the implementation of passive measures, such as massing, orientation, and material selection, complemented by high-efficiency mechanical ventilation systems, photovoltaic cells, energy-efficient appliances and well-insulated façade designs. As a result, the project achieved a Class B environmental performance during the operational phase and a diminished average national CO₂ emission for residential buildings by 80 per cent. The project's carbon production averaged 0.7 tonnes of CO₂ per year, with primary energy consumption ranging from 42 to 58 kilowatt hours per square metre (kWh/m2) (DLUHC, 2021).

What are the potential weaknesses inherent to Knight’s Walk?

Notwithstanding the robust practices that were put in place, several risks were identified, particularly in relation to the design approach that was selected. Although the fabric-first approach is regarded as a fundamental tenet of sustainable construction, it has not been without its detractors. A significant concern is the long-term variability in the performance of fabric-first buildings, which is contingent upon factors such as maintenance practices, occupant behaviour and climate fluctuations. Inadequate construction quality or maintenance practices can result in the deterioration of energy efficiency gains over time, underscoring the need for continuous monitoring and maintenance (Eyre et al., 2023). This could consequently result in a considerable increase in operational costs, thereby jeopardising the objective of housing affordability over the long term. Furthermore, buildings with high insulation using the fabric-first approach may be susceptible to overheating during the warmer seasons in certain climates, particularly if passive cooling strategies are inadequately integrated into the design (Eyre et al., 2023). This can lead to additional energy consumption for cooling purposes and counteract efforts to achieve highly efficient energy.

M.Alsaeed. ESR5

Read more

->

Housing retrofit subsidies in the Netherlands

Created on 20-11-2024

In Europe, the push for energy-efficient housing has led to widespread use of financial incentives such as grants, loans, and tax rebates to encourage homeowners to undertake retrofits. These measures aim to reduce energy consumption and improve the environmental performance of residential buildings. Governments across the continent have adopted various programs to support these efforts, offering significant financial aid to make energy-saving improvements more accessible to homeowners. In addition to subsidies, some countries implement energy taxes to further promote efficiency and fund sustainability initiatives. At the European Union level, comprehensive strategies are being developed to enhance the energy efficiency of buildings, including proposals for new regulatory frameworks and financial incentives. This multi-faceted approach reflects a growing recognition of the importance of sustainable housing in achieving broader environmental and economic goals.

Subsidisation of housing retrofit, through grants and loans, as well as tax rebates are commonly used across Europe to incentivise the energy-efficient retrofit of the housing stock (Castellazzi et al., 2019). Following this trend, the Dutch government has put in place a series of grants and subsidised loans to incentivise retrofit. First, the “Subsidie Energiebesparing Eigen Huis” is a grant programme covering up to 50% of retrofit costs when at least two energy-saving measures improving EPC levels have been implemented. Dutch homeowners can also apply for the Investment Grant for Sustainable Energy Savings (ISDE) in the case of single measures such as solar boilers or heat pumps (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, 2019). Since 2022, 0% interest loans are also available to low-income households from the National Heat Fund.

On the stick side of retrofit incentivation, the Netherlands implements a regressive form of carbon taxation on individual households (Maier & Ricci, 2024). Research by the Dutch National Bank has also alluded to the strong impact of energy taxation on lower incomes and the inelasticity of energy consumption. Havlinova et al. (2022) have found that the introduction of stronger forms of energy taxation in heated energy markets can impinge on lower incomes resulting in regressive distributional impacts. At the EU level, the Renovation Wave is actively promoting this approach to housing retrofit through its proposal to include buildings in the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) together with the implementation of retrofit subsidies(2003/87/EC). As a result, while owner-occupied housing is undertaxed, the tax burden on energy consumption at the household level is poised to increase.

Retrofit subsidies usually come to join fiscal systems favouring owner occupation. These forms of direct subsidisation of housing retrofit coalesce with increases in the fiscal burden on energy consumption. According to Haffner & Heylen (2011), the housing taxation structure favours owner-occupation with a mortgage through large deductions in income tax. In the Netherlands, imputed rent, the main form of housing taxation is calculated on the basis of a notional rent value and then added onto box 1 which comprises labour income. All other income from investments is taxed under box 3 at a different rate. Haffner & Heylen (2011) have analysed the lack of tax neutrality in this system and propose to include the taxation of housing assets under box 3 as a tax-neutral benchmark. In the context of housing retrofit, the favourable fiscal treatment of homeownership comes to join generous subsidies for owner-occupied housing retrofit with no maximum income threshold offered by the Dutch government. A green tax is a viable alternative to incentivise retrofit in a more progressive manner.

The Dutch approach to incentivising housing retrofits exemplifies a broader European commitment to enhancing energy efficiency through a combination of financial incentives and regulatory measures. While generous subsidies and tax incentives significantly benefit homeowners, particularly those with mortgages, the regressive nature of energy taxation presents challenges for lower-income households.

Research indicates that increased energy taxation disproportionately impacts these households, underscoring the need for more progressive solutions. The EU’s Retrofit Wave, along with the proposed inclusion of buildings in the ETS, reflects an ongoing effort to balance these measures. In the context of housing retrofits, a shift towards green taxes could provide a more equitable framework, ensuring that the financial burden and benefits of energy-efficient improvements are more evenly distributed across different income groups.

(This text is an excerpt from : Fernández, A., Haffner, M. & Elsinga, M. Subsidies or green taxes? Evaluating the distributional effects of housing renovation policies among Dutch households. J Hous and the Built Environ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-024-10118-5 )

M.Elsinga. Supervisor, M.Haffner. Supervisor, A.Fernandez. ESR12

Read more

->