Lack of (knowledge on) targeted policy instruments to alleviate energy poverty

Created on 14-11-2024

Across Europe, government response to the energy crisis has been largely untargeted. This has incurred substantial costs, lowered incentives for energy saving among higher earners, redistributed regressively, and caused inflationary pressures. The pervasiveness of this untargeted approach can be attributed to the challenges governments face with outdated welfare systems, making the realisation of 'just transition' principles more difficult. A more targeted approach, while crucial, demands a higher level of administrative capacity and is politically more challenging to sell compared to a policy that benefits everyone broadly. Nonetheless, an increasingly shared viewpoint advocates that the climate transition and its broader societal transformation necessitate government intervention to ensure equitable outcomes.

Systems knowledge

Actors

National government

This actor represents the central governing body and authority responsible for overseeing and managing the affairs of a nation, including policymaking, legislation, and implementation within a certain geographic area.

Local government

This denotes the administrative authority responsible for governing and managing local affairs within a specific geographic area, such as a city, town, or district, through local policies, regulations, and services.

Social housing provider

An entity, often a governmental or non-profit organisation, responsible for offering affordable housing options and related services to individuals or families in need within a community or society.

Method

Policy reform

This refers to the process of making changes, revisions, or amendments to existing policies, laws, or regulations to improve their effectiveness, relevance, or desirability of outcomes.

Capacity building

Enhancing the knowledge, skills, resources, and abilities of individuals and/or organisations to effectively address challenges and implement improvements, such as policy reform.

Tools

Social cost-benefit analysis

This involves evaluating and comparing the societal costs and benefits associated with a particular policy, project, or initiative to inform decision-making and determine its overall impact and effectiveness in achieving certain goals.

Target knowledge

Topic

Energy poverty

Energy poverty refers to the condition where households struggle to meet their basic energy needs for participation in society due to factors such as low income, high prices, poor energy efficiency, and specific energy needs.

Dimension

Governance

This involves networks, systems and processes that steer decision-making, service delivery and policy implementation.

Level

Country

The political structure governs a specific geographical area and accommodates a specific population group.

Transformation Knowledge

No references

Related cases

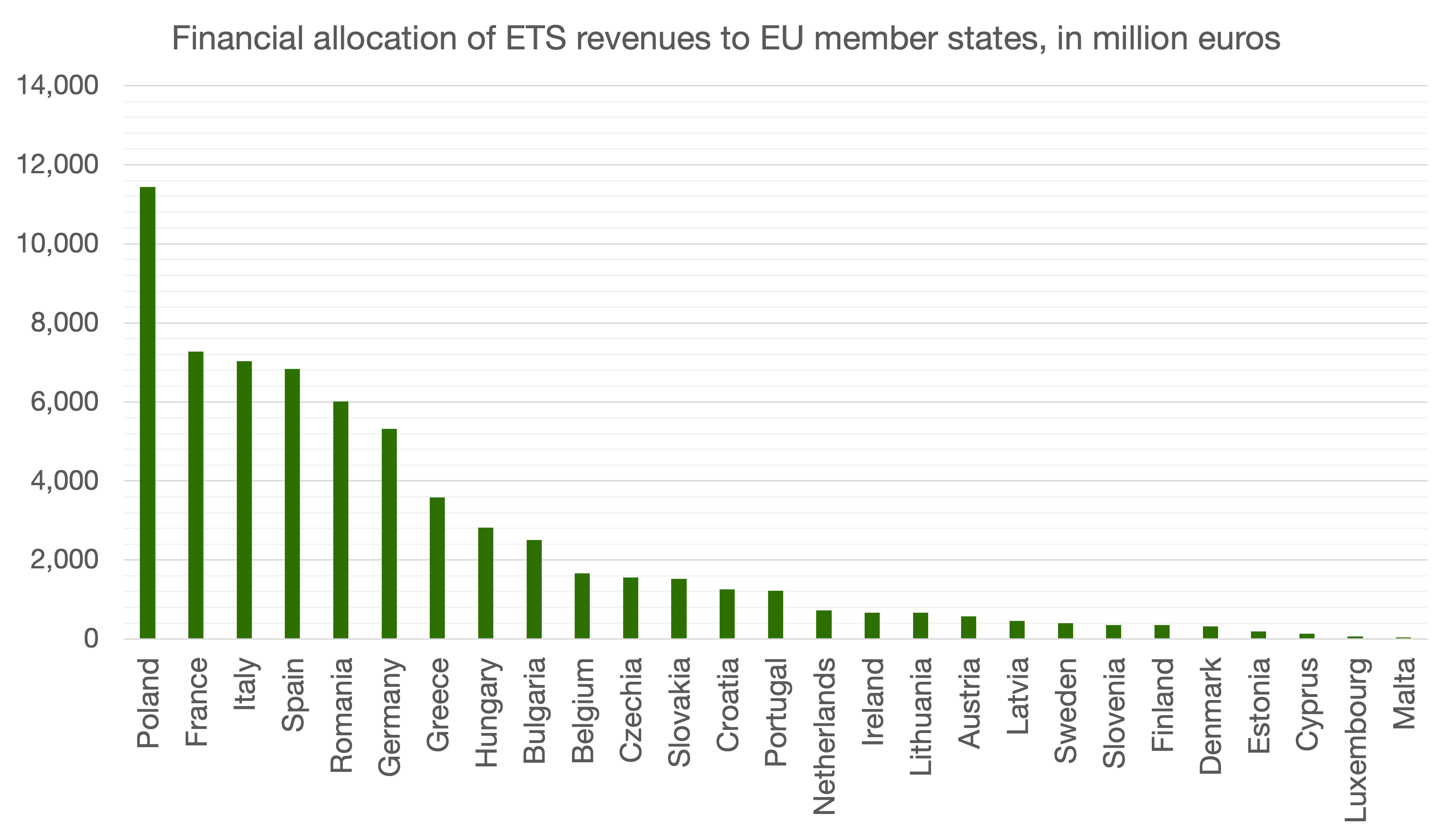

The Social Climate Fund: Materialising Just Transition Principles?

Created on 11-07-2023

Related vocabulary

Housing Governance

Just Transition

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Blogposts

Summer in the City

Posted on 13-06-2023

Conferences

Read more ->