LILAC_Low Impact Living Affordable Community_Leeds

Created on 20-05-2022 | Updated on 09-03-2023

LILAC is an ecological and affordable co-housing project built on a site previously occupied by a school and purchased from the local Council in the Bramley neighbourhood of Leeds, England. LILAC’s agenda towards social, economic, and environmental sustainability emphasises a change in lifestyle beyond a reduction in carbon emissions and improved energy performance. Their ethos incorporates economic justice, behavioural change, wellbeing, mutualism, land ownership, the role of capital and the state, and self-management. LILAC is a bottom-up grassroots initiative based around co-operative governance and cohousing design.

The community-led housing project holistically integrates three major principles: low impact living, affordability, and community. Low impact living is achieved by a combination of environmentally conscious attitudes, sharing of resources, and design-stage nature-based solutions. As the UKs first Mutual Home Ownership Society (MHOS), LILAC’s house prices are designed to remain permanently affordable. Costs are directly linked with average wage growth as opposed to increasing market value. Community at LILAC is heavily facilitated by shared amenities accessed via a common enclosed space and shared resources such as cars, lawnmowers, and power tools. An agreed constitution named ‘community agreements’ guides and informs life in Lilac, covering a range of issues including individual behaviours, interactions with others, and the use and management of shared spaces.

LILAC boasts 20 energy efficient homes with approximately 50 residents, surrounded by landscaping including allotments and biodiversity planting. Construction costs were higher than the UK average. However, a return-on-investment superior to conventional housing includes permanent affordability at 35% of net household income, reduced energy bills, superior housing quality, environmental performance, health, safety, and wellbeing.

Architect(s)

White Design Associates

Location

Leeds, England

Project (year)

2006-present

Construction (year)

2012-2013

Housing type

Mix of one and two bed flats and three and four bed houses. Private gardens, the upper flats have balconies

Urban context

Suburban context on an old school site

Construction system

Prefabricated ModCell wall system built with resident contribution, lime render, triple glazing

Status

Built

Description

Innovative aspects of the housing design/building

The model for LILAC is based on the Danish co-housing model: mixing private space with shared spaces to encourage social interaction. A plethora of green spaces include allotments, pond, a shared garden and a children’s play area. Akin to the private self-contained homes, the ‘common house’ includes a communal workshop, office, post room, food cooperative, kitchen, dining space, social space, bike storage, play area, guest rooms and laundry room. The LILAC community benefit from a large number of communal facilities including: a common house with shared laundry, kitchen, reading area and community area; car sharing; pooling household equipment and power tools; sharing common meals twice per week; growing food in the allotment; and looking for provisions in the local area (LILAC Coop, 2022b; ModCell, n.d.). A shared lifestyle whereby resources and amenities are combined, reduces energy use and saves money.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

Constructed under a Design and Build contract (Chatterton, 2015), LILAC boasts an innovative prefabricated ModCell construction that includes a low carbon timber frame insulated with straw-bale. Residents assisted with the labour, collectively adding the straw bale insulation. External walls and interior finishes are in a lime render, increasing benefits from passive solar heating through thermal mass. Air tightness was prioritised during construction, and triple-glazed windows help to decrease heat loss during winter, allowing for Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery Systems (MVHR) to regulate indoor air temperature. Further energy performance characteristics include solar thermal energy collection for space and hot water heating, 1.25kw solar PV array, with an extra 4kw on the common house (LILAC Coop, 2022b).

LILAC features a flood prevention system whereby a sustainable urban drainage system (SUDS) feeds the central pond. Roof rainwater runoff is collected into water butts that are later used to water the gardens. Overflow from water butts enters the central pond, which discharges into the public drainage system at a reduced rate. Furthermore, all ground surfaces of the site are permeable. Biodiversity planting and a permaculture design certificate course were integrated into the design at planning stage.

Major additional spending decisions were made whenever residents believed it would meet their core values and result in long term financial savings (Chatterton, 2015, p.68). Construction costs were therefore higher than the UK average – a 48 sqm one-bedroom flat cost £84,000 to build at a cost of £1,744 per sqm while the average costs in England were £1,200 per sqm. However, the annual heating demand of the homes is far less than the UK average of 140kWh/m² at around 30kWh/m², reducing energy consumption and bills up to two-thirds compared with existing UK housing stock (Chatterton, 2015, p.84).

Involvement of users and stakeholders

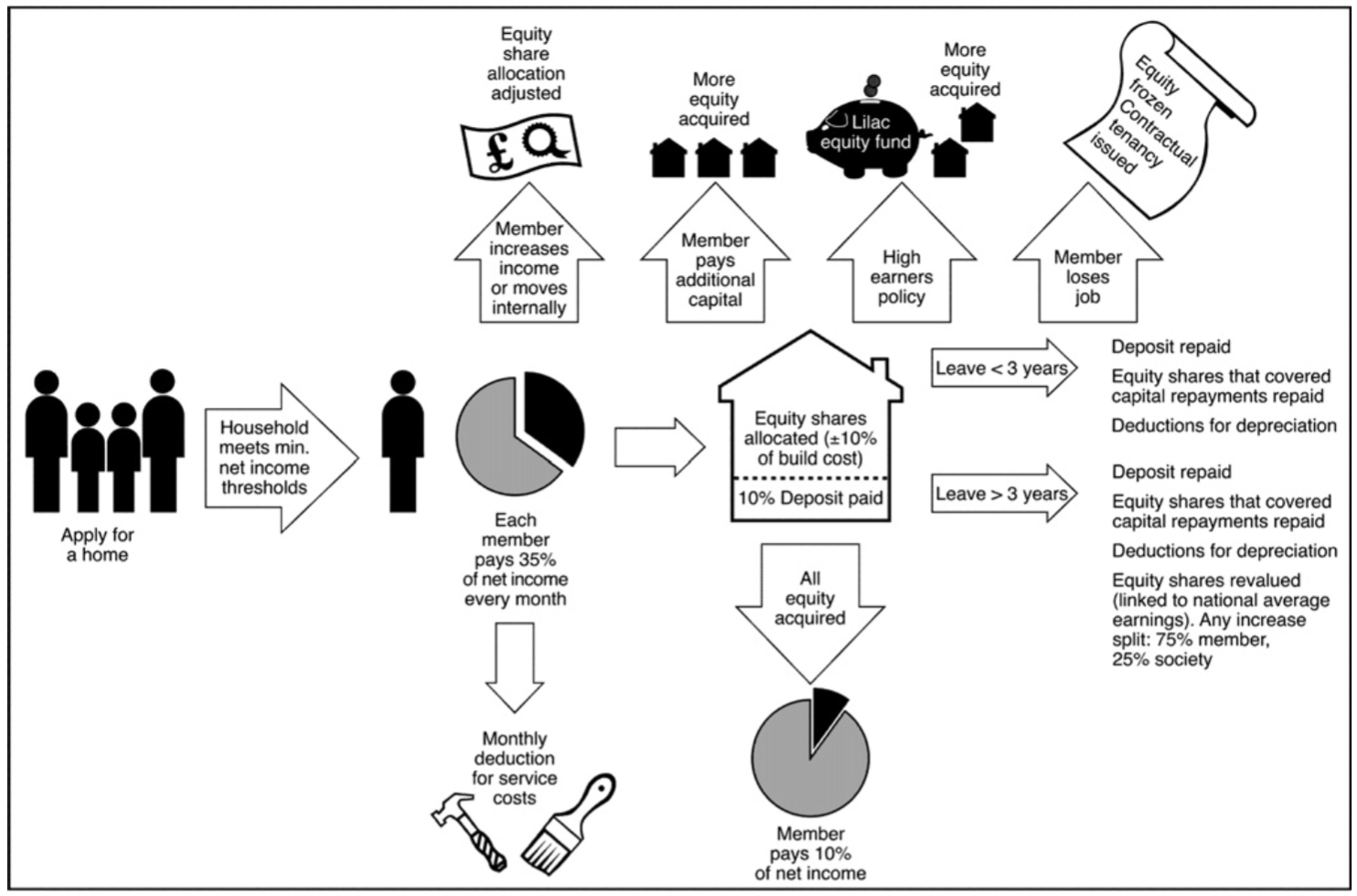

LILAC is owned by a cooperative, through the innovative equity-based model: Mutual Home Ownership Scheme (MHOS). The MHOS is a leaseholder approach (Chatterton, 2013) where residents purchase shares in the co-operative. The number of shares owned by each member is related in part to their income, and partly according to the size of their property. If someone earn a large income their house becomes more expensive, but another property subsequently becomes cheaper, thus conserving affordability. Affordable housing at LILAC is maintained as no more than 35% of net household income should be spent on housing (Chatterton, 2013; LILAC Coop, 2022a).

Minimum net income levels were set for each different house size to ensure a 35% equity share rate generates enough income to cover the mortgage repayments (Pickerill, 2015). The MHOS owns the homes and land and is made up of the residents who also manage LILAC. Members lease and occupy specific houses or flat from the MHOS. In effect, residents are their own landlords.

The building was financed by a combination of personal members invested capital, a long-term mortgage from the ethical bank Triodos, and a government grant of £420,000 from The Homes and Communities Agency’s Low Carbon Investment Fund, specifically to experiment with ModCell straw construction (Chatterton, 2013; Lawton & Atkinson, 2019). Each member makes monthly payments to the MHOS, who then pays the mortgage – deductions are made for service costs. In 2015, annual household minimum income for a home was set as at least £15,000.

‘Community agreements’ cover areas such as pets, food, communal cooking, use of the common house, management of green spaces, equal opportunities, vulnerable adults, the use of white goods, housing allocation and diversity, and garden upkeep (Chatterton, 2013; LILAC, 2021). “MHOS forms the democratic heart of the project” (Chatterton, 2013). All decisions are made democratically, using templates to generate and discuss proposals, explore pros and cons, generate amendments, and ratify decisions (Chatterton, 2013).

Relationship to urban environment

LILAC is in a highly integrated inner-city locality, situated in an urban neighbourhood of Leeds, on a site that was previously a school. Integrating with the wider community in West Leeds, the common house is used for “local meetings, film nights, meals and gatherings, workshops and has been used as the local polling station” (LILAC Coop, 2022b). LILAC has increased residents feeling of empowerment to participate in social action, working within the wider community to explore issues together and work for change. This has included supporting a local community association, local schools and holding charity and music events (LILAC, 2021).

Behaviour and wellbeing

LILACs community act in the knowledge that an adequate response to climate change and energy reduction takes shifting the way we live, enacting behavioural changes that contribute to a post-carbon transition. Decisions in cohousing are made as a community, rather than individual consumers or households. Residents report a much higher health satisfaction – from 58% to 76% – and life satisfaction – from 58% to 87% – compared to previous accommodation (LILAC, 2021). Both physical and mental health improvements have been reported since moving to the community due to LILAC’s “plentiful greenspace, sustainable travel options, better high air quality and natural light in the homes, greater social interaction and opportunities for socialising with neighbours” (LILAC, 2021). Further benefits of LILAC as a cohousing scheme include increased safety and wellbeing, natural surveillance and support for the elderly, reduced car numbers combined with car separation and car-free home zones to increase safety as well as reducing carbon emissions related to car use (Chatterton, 2013).

Alignment with project research areas

Design, planning and building

- An innovative cohousing model in the UK that improves social, environmental, and economic sustainability.

- The homes are designed as inward facing, to increase opportunities for meeting, conversing, and opportunities to watch out, and care for, neighbours.

- The common house is designed to facilitate social interaction, conserve power and energy through sharing resources that limit fuel consumption and integrate with the wider community.

Community participation

- Community involvement is the central core of LILAC at all stages of design, construction and in use. The scheme is based on a shared ideal of the way members want to live as a community, agreed lifestyles, and ‘community agreements’ that guide and inform life at LILAC.

- All decisions are democratically taken through an agreed process, permeating and reinforcing the non-hierarchical community structure.

Policy and Financing

- A MHOS co-operative is better at facilitating finance because it is not possible to obtain a mortgage in the UK for shared spaces. It was also possible to get a better rate for repayments as a large entity, than a collection of individuals.

- The land was purchased directly from the council.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

LILAC responds to the following Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

Goal 1 No Poverty: ensuring ‘affordable housing’ for all residents where total housing costs are less than 35% of household income

Goal 2 No Hunger: Cooperative living, on-site allotment, shared kitchen, food, meals. On-site food production contributed to self-sustained living. Wealthier inhabitants can also help feed the less wealthy inhabitants if needed.

Goal 3 Good health and well-being: Healthy living, outdoor communal work and multigenerational residents

Goal 6 Clean water and sanitation: SUDS

Goal 7 Affordable and clean energy: Passive and mechanical solutions to a reduction in energy costs and carbon output

Goal 9 Industry, innovation and infrastructure: pioneered new sustainable construction methods – ModCell.

Goal 11 Sustainable cities and communities: small scale sustainable eco-village (approx. 50 inhabitants)

Goal 12 Responsible consumption and production: A LILAC household produces around half the waste of an average household, 377 kgs compared to 755 kgs nationally. Bulk buying food from ethical suppliers to reduce waste, a community compost, and on-site food growing (LILAC, 2021).

References

Chatterton, P. (2013). Towards an agenda for post-carbon cities: Lessons from LILAC, the uk’s first ecological, affordable cohousing community. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1654–1674. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12009

Chatterton, P. (2015). Low Impact Living: A field guide to ecological, affordable community building. Routledge.

Pickerill, J. (2015, September). Building Eco-Homes for All: Inclusivity, justice and affordability. Building Local Resilience: Architecture and Resilience on the Human Scale: Cross-Disciplinary Conference. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sofie-Pelsmakers/publication/282665450_The_PassivHaus_Standard_minimising_overheating_risk_in_a_changing_climate/links/562a16b508ae22b1703167d1/The-PassivHaus-Standard-minimising-overheating-risk-in-a-changing-climate.pdf#page=87

Lawton, G., & Atkinson, J. (2019, April 21). Discover Permaculture with Geoff Lawton. Permaculture and Community: LILAC Green Cohousing. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mh96D7zK5q4&t=86s

LILAC. (2021). Living in Lilac: Assessing the first Mutual Home Ownership Society in enabling sustainable living. http://lilac.coop/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Lilac-Impact-July-2021.pdf

LILAC Coop. (2022a). Affordable. LILAC Low Impact Living Affordable Community Coop. https://www.lilac.coop/affordable/

LILAC Coop. (2022b). Low Impact Living. LILAC Low Impact Living Affordable Community Coop. http://www.lilac.coop/low-impact-living/

ModCell. (n.d.). LILAC affordable ecological co-housing. ModCell Straw Technology. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from https://www.modcell.com/projects/lilac-affordable-ecological-co-housing/

Related vocabulary

Housing Affordability

Social Housing

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 17-06-2023

Read more ->Related publications

Alsaeed, M., Hadjri, K., & Nawratek, K. (2024, March). A comparative analysis of UK sustainable housing standards. In 7th Residential Building Design & Construction Conference, Pennsylvania, USA.

Posted on 27-07-2024

Conference

Read more ->Blogposts

The “regeneration wave”, hopefully not another missed opportunity to create social value

Posted on 15-07-2023

Summer schools, Reflections

Read more ->

The discussion for the right to housing. ENHR, Barcelona 2022

Posted on 12-09-2022

Conferences, Reflections

Read more ->