Decoding 'new' housing paradigms

Posted on 13-01-2022

Several attempts to elicit guidelines that holistically respond to the issue of understanding and creating an adequate built environment have been produced, especially since the second half of the previous century. Some of them are recognised and elevated as fundamental readings for urbanists and architects alike. However, the principles of what makes a good public space or the ideal spatial configuration of a housing complex, or the adequate allocation of open spaces and communal areas to recognise the needs of children; keep being ignored or at least relegated to theoretical scenarios held in academic setups or one-off experimental works.

Buildings can be studied from a range of tenets, and through history there has always been a dominating paradigm. For Vitruvius, for instance, the ruling qualities that any architectural work might embody were compiled in three, i.e., firmitatis, utilitatis, venustatis, or stability, utility and beauty, those would be detailed in his influential book De Architectura. In the XX century, in full swing of the modernist movement, Le Corbusier portrayed what would become one of the most ground-breaking books in architecture, vers une architecture (1923), enunciating a new way of living and inhabiting, which in turn was followed by a series of principles that dictated the key elements to accomplish ‘good’ architecture with a particular fixation on residential buildings[1]. Form follows function, was one of the maxims that spearheaded modernist architecture and depicted the decided break up with the past, ornament in buildings would then become unnecessary and anachronic. The zeitgeist of each era fluctuates to respond to the most demanding needs inherent to that moment in time.

From housing standardisation to adaptation

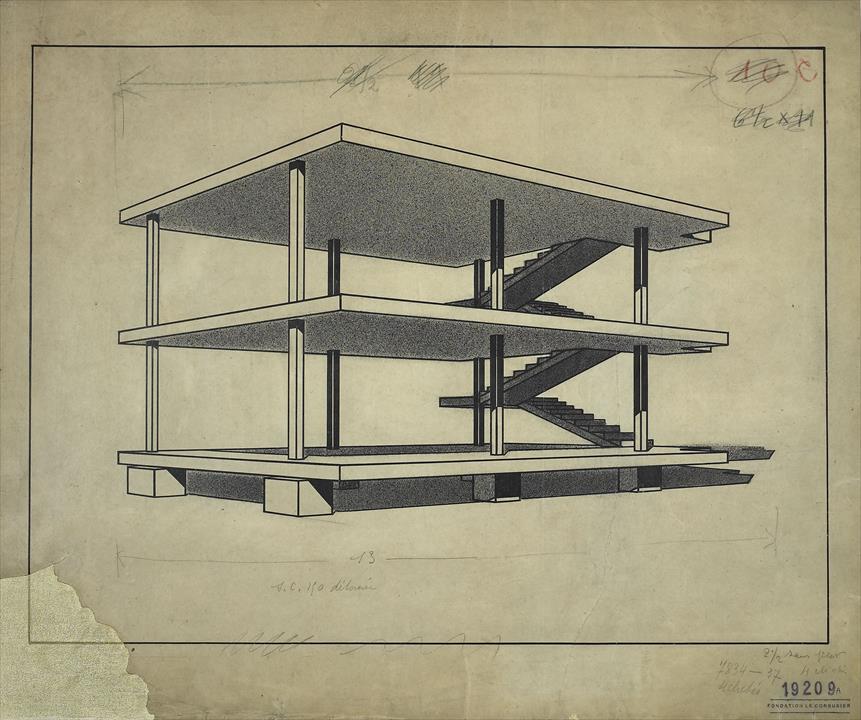

The housing design that follows flexibility and adaptability tenets is not a novelty in architecture, a feature that can be traced in Mies van der Rohe’s Weissenhofsiedlung (1927), or even more than a decade before that with Le Corbusier’s modular prototype the Maison Dom-Ino (1914); the concept has been re-introduced by few contemporary authors like Jeremy Till and Tatjana Schneider, as a response to current housing struggles. According to them, flexible housing should be at the forefront of the contemporary housing agenda. By avoiding the obsolescence that comes with the short-termed mono-functional housing design, and replacing it with a long-term capacity to re-adapt to evolving needs and accommodate multiple ways of life, flexibility by design renders a solution that equates with sustainable practices very much needed in the housebuilding sector.

Nowadays, climate degradation and the urgency of reducing carbon emissions have catapulted sustainability as a term that become part of the everyday jargon in a wide array of fields, an acute issue that has been at the forefront of the international debate in the recent COP26 summit in Glasgow in 2021. Architecture and the built environment are not exempt from this trend[2]. It has been argued that sustainability cannot be attained solely by using energy-friendly technologies, or incorporating labels like LEED or evaluation protocols like BREEAM (BRE Environmental Assessment Method). The triple bottom line of sustainability asserts a social dimension, and other interpretations go even further considering a fourth cultural variable attached to it (see the circles of sustainability). In that specific and often neglected niche, that of social and cultural sustainability, this study purports to focus on the housing domain.

Perhaps one of the most harmful practices of the housebuilding sector is the fact that, akin to a tech company, the products, in this case, dwellings, are planned for obsolescence. Numerous examples of designing housing for obsolescence are portrayed by Till and Schneider in their seminal book Flexible Housing (2007). They contend that such a mindset, mainly enforced by developers and architects during the design stages of a project, is the culprit of major disturbances in the urban layout in cities nowadays. Energy poverty, speculation, gentrification, spiralling land cost and urban segregation, could be attributed, at least to some extent, to poor planning practices and an impossibility, deliberate or accidental, of thinking of housing as the most important asset in our cities. This implies bearing in mind the whole life-cycle of a project and the consequences that go beyond the handover of a housing unit. Thus, a dwelling must be seen as an activity rather than seen as an object. And similarly perceived as a social asset rather than as an economic asset from a consumerism perspective. A rather complementary vision to the one contended by John Turner already in 1976 in Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Buildings Environments. Whereby, though in a totally different context, the barriada or informal settlement in Peru, he recognises housing as a process in which the users are directly implicated.

The process or the housing pathway derived from the housing practices as Clapham suggests (2002), evidence that the evolution of a housing development, along with people's housing careers, continues very much after dwellings have been sold or rented; and therefore, there must be a different approach towards housing design and production. As Till and other authors argue, flexibility and adaptability do not mean that architects are no longer relevant or that every design decision is passed to the users. Architects, according to these precepts, work more as enablers or facilitators, a veritable different approach from the controlling and godlike paradigm that accompanied architectural practice in the XX century, especially during modernism. A good design goes beyond the moment a project is handed over, the life-cycle of a housing scheme must be fully considered from the initial stages of design. A good design is one that recognises that needs change over time and that users are not static, families are formed, grow and reduce. As opposed to what Andrew Rabeneck has called ‘tight-fit-functionalism’, that is the design that follows specific requirements and that can only accommodate determined uses designated by a type of furniture layout. This attitude condemns the typology, and by extension the building, to obsolescence. That is a house that can only accommodate a family-type, a default user. Lifestyles are more fluid than ever before, the way people live has evolved especially in multicultural setups. It is no longer possible to make generalising assumptions over people needs and expectations. In other cultures, the notion of a house might have different connotations than in a traditional north European scenario. Yet, housing solutions seem to fail to respond effectively to a myriad of ways of life and aspirations. These challenges are not new and as it has been established, these debates were held decades ago. Nevertheless, the same question that Marcus and Sarkissian made in their book Housing as if people mattered: Site design guidelines for the planning of medium-density family housing (1986), four decades in the past, still remains: “If research on people-housing relations now exists, why are the design professions not using it?” (p.5).

The empirical research that my thesis is pushing forward purports to give equitable significance to what happens inside, outside and in-between dwellings, and that is the reason that supports the intertwining of Marcus and Sarkissian’s work with the one of Schneider and Till. Marcus and Sarkissian put it clearly when insisting:

“A particular program, and the resulting built environment, may be well conceived to cope with the current daily needs of, say families with young children, but what happens when the children become teenagers or when half of the original nuclear families become single-parent families or grouping of unrelated adults? Design flexibility is often recommended, but an ambiguous space in year I is often equally ambiguous (and leads to equally ambiguous serious problems) in year 15.” (p.7)

One of the main misconceptions that as many authors cited before this research aim to address, is the idea of housing seen as a disposable commodity. People should not have to move out when their personal circumstances change, because their dwelling is not suitable anymore. Such a capitalist view of real estate, especially housing, is not socially responsible let alone environmentally sustainable. Housing provision seen through the lenses of affordability and sustainability goals must incorporate POE, social value and flexibility whether it intends to holistically respond to current concerns. When carrying out Post-occupancy evaluation of a regeneration project there are a series of tenets that shall be permanently referred to during the data collection: User participation, Flexibility by design, Affordability by design and sustainability. Then it will be clear what makes a regeneration project succeed and what aspects are crucial to monitor. This is where the responses and data collected can come in handy. As an analogue research endeavour to that carried out by Marcus and Sarkissian, this research can possibly deliver an updated roadmap for generating social value through regeneration schemes to be further applied, in this case by Clarion in other ventures. Likewise, any housing association, social landlord or non-profit investor that is actively involved in regeneration schemes, can consider these aspects as part of its comprehensive social value approach.

[1] In Les cinq points de l'architecture moderne (1927), Le Corbusier along with Pierre Jeanneret, would compile their recipe of the modern architecture : The Pilotis, Roof gardens, Free plan, Ribbon windows, and Free façade. The Unité d'habitation in Marseille (1952) represents the epitome of these principles applied to residential architecture, a formula that would be further implemented in other sites in the years on.

[2] Especially knowing that at least 8% of global emissions are produced by the cement industry alone without considering other unsustainable building techniques (Ellis, et al. 2020).

References

Clapham, D., 2002. Housing pathways: A post modern analytical framework. Housing, theory and society, 19(2), pp.57-68.

Ellis, L.D., Badel, A.F., Chiang, M.L., Park, R.J.Y. and Chiang, Y.M., 2020. Toward electrochemical synthesis of cement—An electrolyzer-based process for decarbonating CaCO3 while producing useful gas streams. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(23), pp.12584-12591.

Le Corbusier, 1946. Towards a new architecture. London: Architectural Press.

Marcus, C.C. and Sarkissian, W., 1986. Housing as if people mattered: Site design guidelines for the planning of medium-density family housing (Vol. 4). Univ of California Press.

Rabeneck, A., Sheppard, D. and Town, P., 1973. Housing flexibility. Architectural Design, 43(11), pp.698-727.

Rowland, I.D. and Howe, T.N. eds., 2001. Vitruvius:'Ten books on architecture'. Cambridge University Press.

Schneider, T. and Till, J., 2007. Flexible housing. Architectural press.

Schneider, T. and Till, J., 2005. Flexible housing: opportunities and limits. Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 9(2), pp.157-166.

Till, J. and Schneider, T., 2005. Flexible housing: the means to the end. ARQ: architectural research quarterly, 9(3-4), pp.287-296.

Turner, J., 1976. Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments. Marion Boyars Publishers.

Author:

L.Ricaurte

(ESR15)