Flexwoningen Oosterdreef

Created on 08-02-2024 | Updated on 09-02-2024

The Oosterdreef project in Nieuw-Vennep, Netherlands, is a great example of collaboration between national and local stakeholders to quickly provide housing solutions to combat the housing shortage that affects certain regions while at the same time innovating in planning and construction methods. This project exemplifies one of the most recent approaches in housing provision developed in the Netherlands -the Flexwonen model. The national government has launched an ambitious campaign to accelerate the production of housing across the country, and perhaps one of the most compelling aspects of the endeavour is to develop a more dynamic and responsive housing market that can meet both short-term and long-term demands. By supporting more efficient construction methods and making the housing stock more resilient, the Flexwonen model has spearheaded the government’s housing approach. In this context, the municipality of Harlemmermeer, along with Ymere, one of the largest housing corporations in the country, and FARO architects have come together to create a housing project that stands out for its innovative building techniques, planning process, design and community building approach.

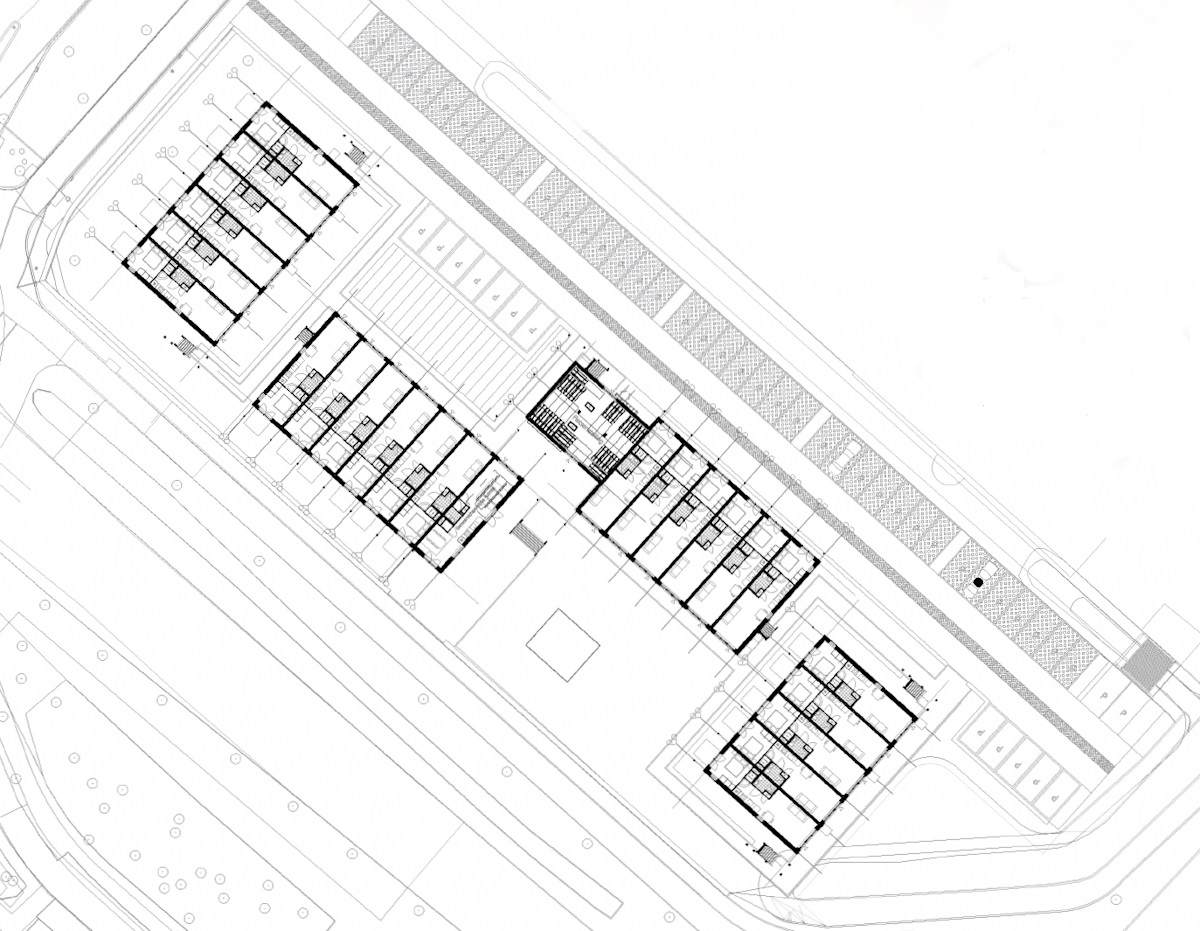

The project consists of 60 one-bedroom flats arranged in low-rise blocks, featuring common spaces and facilities, situated on a temporary site over fifteen years. The project targets specific population groups often overlooked by the constrained social housing supply and facing difficulties in the private housing market. The project integrates innovative planning tools with efficient construction methods, thereby reducing construction time and addressing the urgent need for housing in the region.

Architect(s)

FARO Architects, Ymere, Homes Factory

Location

Nieuw-Vennep, Netherlands

Project (year)

2022

Construction (year)

2022

Housing type

Multifamily housing: Flexwoningen (temporary housing 15 years), 60 flats

Urban context

Suburban

Construction system

Prefab construction/movable

Status

Built

Description

Background

The soaring housing shortage in the Netherlands has prompted national and local governments to come up with innovative solutions to cater for the ever-increasing demand. The Flexwonen model is a response to the need to provide homes quickly and to foster circularity and innovation in the construction sector. The model is crafted to meet the housing needs of people who cannot simply wait for the lengthy process of conventional housing developments or cannot afford to remain on the endless waiting list to be allocated a home.

Flexibility is its main characteristic. This is reflected not only in the design and construction features of the housing buildings, but also in the regulatory frameworks that make them possible. The faster the units are built and delivered, the greater the impact on people’s lives. This dynamic approach, which adapts to existing and evolving circumstances of homebuilding, relies on collaboration between stakeholders in the sector to streamline the procurement and building process. All of this is accompanied by an integrated approach to placemaking, exemplified by the partnership with a local social organisation, the involvement of a community builder, the provision of spaces for residents to interact and get to know each other, the project's target groups and the beneficiary selection process.

Flexwonen can have a significant impact on municipalities and regions that are severely affected by housing shortages, especially those lacking sufficient land and time to develop traditional housing projects. Due to its temporary nature, homes can be built on land that is not suitable for permanent housing. This streamlines the building process and allows the development of areas that are not currently suitable for housing, both in urban and peri-urban zones. After the initial site permit expires, the homes can be moved to another site and permanently placed there.

Recent developments in construction techniques and materials contribute to raising the aesthetic and quality standards of these projects to a level equivalent to that of permanent housing, as the case of Oosterdreef in Nieuw-Vennep demonstrates. Nevertheless, this model, propelled by the government in 2019 with the publication of the guide ‘Get started with flex-housing!’ and the ‘Temporary Housing Acceleration taskforce’ in 2022 (Druta & Fatemidokhtcharook, 2023), is still at an embryonic stage of development. The success of the initiative and its real impact, especially in the long term, remain to be seen.

Analogous housing projects have been carried out in other European countries, such as Germany, Italy, and France among others (See references section). Although their objectives and innovative aspects resonate with the ones of Flexwonen in the Netherlands, the nationwide scope of this model, sustained by the commitment and collaboration between national and local governments, social housing providers and contractors, is taking the effects of policy, building and design innovation to another level.

Involvement of stakeholders

The national government's aim to establish a more dynamic housing supply system, capable of adapting to local, regional or national demand trends in the short-term, has prompted municipalities like Haarlemmermeer to join forces with housing corporations. Together, they venture into the production of housing that can leverage site constraints while contributing to bridging the gap between supply and demand in the region.

Thanks to its innovative, flexible and collaborative nature, the Oosterdreef project was completed in less than a year after the first module was placed on the site. The land, which is owned by the municipality, is subject to environmental restrictions due to the noise pollution caused by its proximity to Schiphol airport, meaning that the construction of permanent housing was not feasible in the short term. Nevertheless, the pressing challenge of providing housing, especially for young people in the region, priced out by the private market, has led the municipality to collaborate with a housing corporation and an architecture firm. Together, they have developed a ‘Kavelpaspoort’ (plot passport), a document that significantly expedites the building process.

The plot passport is a comprehensive framework that summarises a series of requirements, restrictions, guidelines and details in a single document, developed in consultation with the various stakeholders involved. Its main purpose is to expedite the construction process. Its various benefits include helping to shorten the time it takes for the project to be approved by the relevant authorities, facilitating the selection of a suitable developer and contractors, and avoiding unforeseen issues during construction. The document is also an effective means of incorporating the voices of relevant stakeholders, including local residents before any work begins on the site. This ensures transparency and participatory decision-making. In Oosterdreef, Ymere, the housing corporation that manages the units, and FARO, the architecture firm commissioned with the design, played pivotal roles in drafting the document in collaboration with the municipality of Haarlemmermeer. Their main objective was to swiftly build houses using innovative construction techniques and to provide much-needed housing on a site that was underused due to land restrictions.

Project’s target groups and selection process

Perhaps one of the most compelling aspects of the model is the diverse group of people it intends to benefit. The target groups of Flexwonen vary according to context and needs, as the municipalities are in charge of establishing their priorities. In the case of Oosterdreef, Ymere and Haarlemmermeer aim for a social mix that not only contributes to solving the housing shortage in the region, but also supports the integration process of the status holders. The selection of status holders, i.e. asylum seekers who have received a residence permit and therefore cannot continue living in the reception centres, who would benefit from the scheme, was carried out in collaboration with the municipality and the housing corporation. As most of these residents did not previously live in the local area, as the central government determines the number of status holders that each municipality must accommodate, the social mix is attained by also including local residents. In this case, they were allocated a flat in the project based on a specific profile, as the flats were designed for single people. The project, which comprises 60 dwellings, is therefore deliberately divided to accommodate 30 of the above-mentioned status holders and 30 locals.

In addition, the group of locals was completed with emergency seekers (‘Spoed- zoekers’) and starters. The emphasis that the project's focus on this population swathe emphasises its social function. Emergency seekers are people who are unable to continue living in their homes due to severe hardship, including circumstances that severely affect their physical or mental well-being, and who are otherwise likely to be at risk of homelessness. This includes, for example, victims of domestic violence and eviction, but also people going through a life-changing situation such as divorce. On the other hand, starters, in this project between the ages of 23 and 28, refer to people who long to start on the housing ladder, e.g., recent graduates, young professionals, migrant workers and people who are unable to move from their parental home to independent living due to financial constraints.

Finally, local residents interested in the project were asked to submit a letter of motivation explaining how they would contribute to making Oosterdreef a thriving community, in addition to the usual documentation required as part of the process. Thus, a stated willingness to participate in the project was deemed more important than, for example, a place on the waiting list, demonstrating the commitment of the housing corporation and local authorities to creating a community and placemaking.

Innovative aspects of the housing design

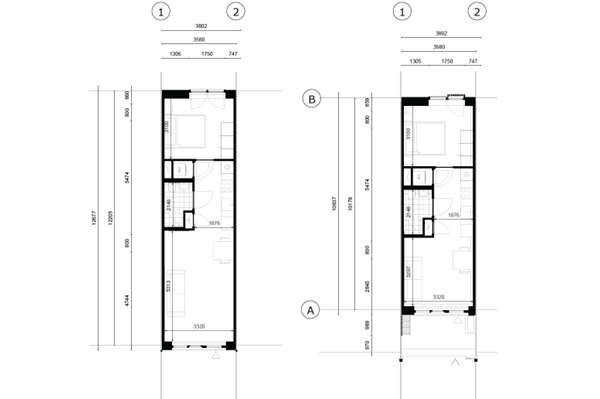

Although this model has been applied to a range of buildings and contexts, from the temporary use of office space to the retrofitting of vacant residential buildings and the use of containers in its early stages of development (which has had a significant bearing on the stigmatisation of the model), one of the most notable features of the government's current approach to scaling up and accelerating the model is its support for the development of innovative construction techniques. The use of factory-built production methods such as prefabricated construction in the form of modules that are later transported to the site to be assembled could help to establish the model as a fully-fledged segment of the housing sector. An example of this is Homes Factory, a 3D module factory based in Breda, which was chosen as the contractor. Prefab construction not only significantly reduces the construction phases, but also makes it easier to relocate the houses when the licence expires after 15 years, which contributes to its flexibility.

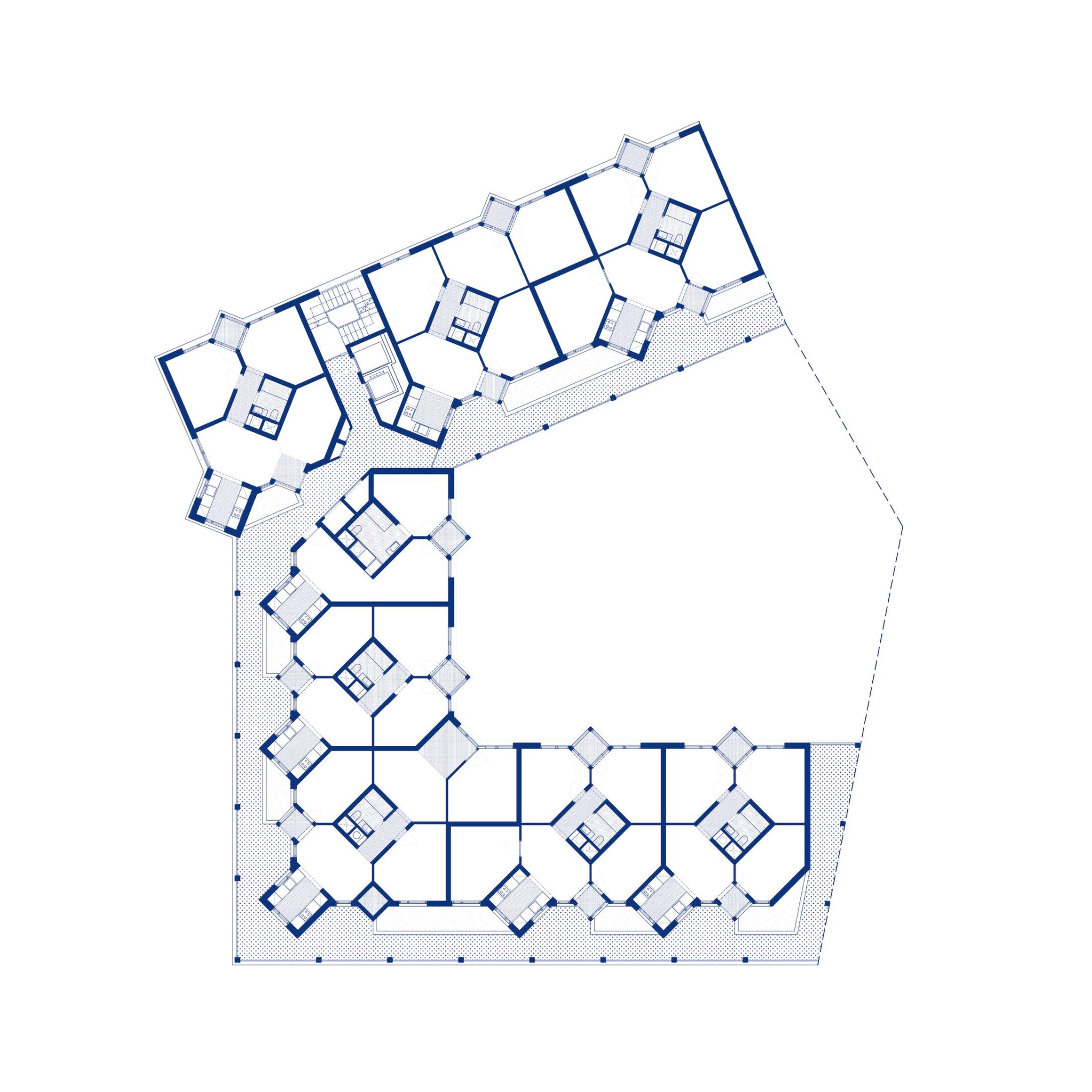

The architecture firm FARO played a crucial role in shaping the plot passport, which incorporated details on the design and layout of the scheme. The objective was to encourage social interaction through shared indoor and outdoor spaces, organized around two courtyards. These courtyards are partially enclosed by two- and three-storey blocks, featuring deck access with wider-than-usual galleries with benches that offer additional space for the inhabitants to linger. Additionally, facilities such as letterboxes, entrance areas, waste collection points, and covered bicycle parking spaces were strategically placed to foster spontaneous encounters between neighbours. Some spaces, such as the courtyards, were intentionally left unfinished to encourage and enable residents to determine the function that best suits them. This provides an opportunity for residents to get to know each other, integrate, and cultivate a sense of belonging.

Within the blocks, the prefab modules consist of two different housing typologies of 32 m2 and 37 m2. One of these units on the ground floor was left unoccupied to be used as a common indoor space. The ‘Huiskamer’ or living room according to its English translation, is strategically located at the heart of the scheme, adjacent to the mailboxes and bicycle parking space. Besides serving as a place for everyone to meet and hold events, it is the place where a community builder interacts and works with the residents on-site.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

The environmental sustainability of the building was at the top of the project's priorities. Off-site construction methods offer several advantages over traditional techniques, including reduced waste due to precise manufacturing at the factory, efficient material transport, less on-site disruption, shorter construction times and the reusability and circularity of the materials and the units themselves. The choice of bamboo for the façades also contributes to the project's sustainability. Bamboo is a highly renewable and fast-growing material compared to traditional timber, with a low carbon footprint as it absorbs CO2 during growth (linked to embodied carbon). It also has energy-efficient properties, such as good thermal regulation, which leads to lower energy consumption (operational carbon). This is complemented by a heat pump system and solar panels on the roofs of the buildings.

“The only thing that is not permanent is the site”

This sentiment was shared by many, if not all, individuals involved in the project whom I had the opportunity to interview for this case study. The design qualities of the project meet the standards expected for permanent housing. One of the main challenges faced by projects of this type is the perception, increasingly erroneous, that their temporary nature implies lower quality compared to permanent housing.

In this case, the houses were designed and conceived as permanent dwellings, the temporary aspect is only linked to the site. When the 15-year licence expires, the homes will be relocated to another location where they can potentially become permanent. They can also be reassembled in a different configuration if required, a possibility granted by the modular design of the dwellings.

Integration with the community

The residents were selected with the expectation that they would contribute to building a community and support the permit-holders to better adapt and integrate into the local community and surroundings. Ymere, together with a local social organisation, helps new residents in this process of integration. During the first two years following the completion of the construction phase, concurrent with tenants moving into their new homes, an on-site community builder works with residents to help them forge the social ties that will enable the development of a cohesive and thriving community. The community builder has organised a range of social activities and initiatives in collaboration with the residents in the shared spaces. These include piano lessons, communal meals, sporting activities and ‘de Weggeefkast’, or the giveaway cupboard, a communal pantry aimed at fostering a sense of neighbourly sharing and cooperation.

Alignment with project research areas

Design, planning and building (Highly related)

- The use of industrialised construction techniques and innovation in the sector is a key element of the Flexwonen model promoted by the government. The team of architects has endeavoured to improve the overall design and look of the project. In the past, Flexwonen was often perceived as having a container-like appearance, mainly because of its temporary nature and the look of its earlier versions. The team has also paid close attention to the design specifications and materials to ensure they are on par with those used in permanent buildings.

- The planning process was streamlined using the ‘Kavelpaspoort’, or plot passport. Collaboration between the various stakeholders involved in the creation of this document has sped up the process of obtaining planning permission. The use of these planning tools in combination with prefabricated modules has considerably shortened the construction phase.

Community participation (Moderately related)

- Local residents were consulted and participated in the creation of the plot passport, enhancing the integration of the housing scheme and the new residents in the local community. Additionally, the project aimed to alleviate the local housing shortage, ensuring that some of the potential beneficiaries could be from the local area. During the design process, FARO, in collaboration with the municipality of Haarlemmermeer, held multiple consultation meetings to gather different perspectives on the project, which included sessions specifically inviting permit holders, one of the target groups of the project, with an architectural background to share their experiences and expectations regarding temporary accommodation. This facilitated a deeper understanding of their needs and expectations and helped to identify potential design solutions. Key considerations centred on the value of shared spaces and communal areas that invite residents to linger. Notably, one participant in the sessions was later employed by the architectural firm and ended up playing a pivotal role in the design and construction of the project.

- The design has left the definition and use of the courtyards open so that future residents can decide on their functions. Recently, residents held meetings with the housing corporation managing the project to discuss various options and determine the features to be incorporated into the courtyards.

Policy and financing (Highly related)

- This project became feasible due to policy breakthroughs at the national level, aimed at creating a more dynamic housing market capable of responding more rapidly and efficiently to the overall housing shortage.

- Flexible policy instruments and regulatory frameworks enable local governments to access funding and expertise, facilitating the broader implementation of the model across the country.

- The potential for reusability of the housing stock after the initial licence expires, coupled with shorter planning and construction phases, helps alleviate financial constraints and mitigate the risks perceived by housing actors in the past. This contributes to making a stronger case for such housing projects.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

1. No poverty: End poverty in all its forms everywhere (Target: 1.3; 1.4; 1.5)

Access to affordable rent and a secure tenancy for up to 15 years can have a significant impact on residents’ finances, particularly benefiting young people and permit holders. (Highly related)

3. Good health and well-being: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages (Target: 3.4; 3.9)

Securing a roof over one’s head, especially for emergency seekers who would otherwise be homeless or living in a potentially threatening environment, and the sense of control over one's living conditions, have a positive impact on the person’s wellbeing, as expressed by the interviewed residents. (Highly related)

5. Gender equality: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls (Target: 5.a)

According to a survey conducted by the Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History in EU Member States, 45% of the 1,500 Dutch women surveyed have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at some point in their lives. Additionally, one in five women has been physically abused by their partner or ex-partner and 3% have avoided their own home in the last year due to the fear of violence. These compelling statistics underscore the importance of providing a home for victims of domestic violence, which includes a significant number of women. The project targets emergency seekers, which includes this group of people. (Highly related)

7. Affordable and clean energy: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all (Target: 7.1; 7.2; 7.3)

The achieved energy efficiency is due to the use of prefab construction methods and energy-efficient materials and technologies such as heat pumps and solar panels. This comprehensive approach helps reduce both embodied and operational carbon emissions. (Highly related)

11. Sustainable cities and communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable (Target: 11.1; 11.3; 11.7; 11.a; 11.b)

While environmental and economic sustainability are key focuses of the project, equal attention has been given to social sustainability. Collaboration with local actors, along with the introduction of a community builder, ensures cohesion among new residents and the broader community. (Highly related)

12. Sustainable consumption and production: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns (Target: 12.5; 12.7; 12.8)

The construction methods and planning processes involved were intended to reduce waste and accelerate the project’s construction. (Highly related)

13 Climate action: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts (Target: 13.1; 13.2; 13.3)

The resilience of this housing model is underscored by the fact that units can be relocated and reused. Innovative industrial construction methods hold significant potential to enhance the capacity of housing providers to respond promptly to climate shocks and emergencies. (Highly related)

References

Druta, O., & Fatemidokhtcharook, M. (2023). Flex-housing and the advent of the ‘spoedzoeker’ in Dutch housing policy. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2023.2267834

Bouw flexwoningen aan de Oosterdreef in Nieuw-Vennep van start. Nieuws.nl. (2022, March 5). https://haarlemmermeer.nieuws.nl/nieuws/100419/bouw-flexwoningen-aan-de-oosterdreef-in-nieuw-vennep-van-start/

Expertisecentrum Flexwonen. (2019, January 18). Handreiking aan de Slag met flexwonen!. Handreiking Aan de slag met flexwonen! – flexwonen.nl. https://flexwonen.nl/handreiking-aan-de-slag-met-flexwonen/

FARO Architecten. (2023, February 20). Flexwonen Oostertuin, Nieuw-Vennep: 60 Tijdelijke Woningen. FARO Architecten. https://faro.nl/projecten/flexwonen-oosterdreef/

FARO Architecten. (2022a, October 27). Flexwonen Nieuw-Vennep in de Volkskrant. FARO Architecten. https://faro.nl/nieuws/flexwonen-nieuw-vennep-in-de-volkskrant/

FARO Architecten. (2022b, December 13). Minister de Jonge Bezoekt flexproject Oostertuin in Nieuw-Vennep. FARO Architecten. https://faro.nl/nieuws/minister-de-jonge-bezoekt-flexproject-oostertuin-in-nieuw-vennep/

FARO Architecten. (2023, January 19). Permanente Kwaliteit Flexwoningen Oostertuin. FARO Architecten. https://faro.nl/nieuws/permanente-kwaliteit-flexwoningen-oostertuin/

InforMeer. (2022, September 9). Flexwonen Oosterdreef Genomineerd. Gemeente Haarlemmermeer. https://www2.haarlemmermeergemeente.nl/nieuws/flexwonen-oosterdreef-genomineerd

Nilan Netherlands. (2023, June 5). Nilan compact S: Ventilatie Warmtepomp: Flexwoningen. Nilan Netherlands. https://www.nilannetherlands.nl/post/nilan-compact-s-flexwoningen

Redactie de Architect. (2022, July 18). Arc22: Flexwonen Oosterdreef, Nieuw Vennep - Humanex/Faro Architecten. de Architect. https://www.dearchitect.nl/273318/arc22-flexwonen-oosterdreef-nieuw-vennep-faro-architecten

Rooyakkers, E. (n.d.). Van plan tot oplevering: 60 woningen klaar in 2 jaar. Aedes Magazine. https://aedesmagazine.nl/1-2023/houtbouw-nieuw-vennep?utm_source=linkedin&utm_medium=aedesmagazine&utm_campaign=12023&utm_term=verbinden&utm_content=hoedan

Woonbedrijf. (n.d.). Flexwonen Snel een woning, met een tijdelijk contract. Woonbedrijf. https://www.woonbedrijf.com/flexwonen

Ymere. (2021, March 29). Huurhuis Nodig? Snelle woning is aantrekkelijke optie. Huurhuis nodig? Snelle woning is aantrekkelijke optie. https://www.ymere.nl/nieuws/nieuwsberichten/2021-03-29-huurhuis-nodig-snelle-woning-is-aantrekkelijke-optie/

Ymere. (2021, November 17). Gemeente Haarlemmermeer en Ymere Werken Samen aan 60 flexwoningen in Nieuw-Vennep. Ymere. https://www.ymere.nl/nieuws/nieuwsberichten/2021-11-17-gemeente-haarlemmermeer-en-ymere-werken-samen-aan-60-flexwoningen-in-nieuw-vennep/

Ymere. (2022, September 2). Gezocht: Gemotiveerde Huurders voor Nieuwbouwwoningen oosterdreef. Ymere. https://www.ymere.nl/nieuws/nieuwsberichten/2022-9-2-gezocht-gemotiveerde-huurders-nieuwbouwwoningen-oosterdreef/

Similar projects in Europe

Arquitectura Viva. (2020, December 14). Modular Housing for Refugees, Berlin. https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/viviendas-modulares-para-refugiados-0

Graftlab. (n.d.). HEIMAT2. GRAFT. https://graftlab.com/en/projects/heimat2

OCHA. (2021, February 3). Housing for Migrants and Refugees in the UNECE Region: Challenges and practices. https://reliefweb.int/report/germany/housing-migrants-and-refugees-unece-region-challenges-and-practices

Related vocabulary

Design for Disassembly

Flexibility

Industrialised Construction

Social Sustainability

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 18-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 19-06-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 09-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Blogposts

Architecture enables, not dictates ways of life. Good design doesn’t have to come with a hefty price tag

Posted on 02-11-2023

Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

Towards flexible and industrialised housing solutions

Posted on 24-02-2023

Secondments

Read more ->