Can70 senior cooperative housing: Aging in community

Created on 12-09-2024 | Updated on 22-04-2025

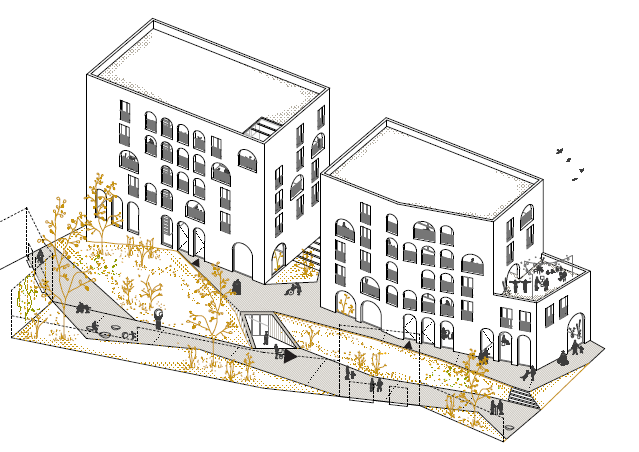

Can70 is the first senior co-housing project in the city of Barcelona and the first to be constructed on public land in Spain under the grant-of-use regime. It is a housing project within the umbrella of Sostre Civic, a cooperative of projects. Can70 pioneers a new model for aging, centred on mutual support, collective living and democratic governance, where residents are empowered to shape their own futures. The vision for Can70 began in 2015 when a group of friends came together to explore alternative ways to live as they aged. Their journey involved years of community-building, advocacy, and logistical challenges: from securing institutional support and financing, to acquiring suitable land. A major milestone was reached in 2021 when the group was granted a 99-year lease on a public plot by the city council, marking a powerful example of public-community partnership. The project introduces several innovations in housing provision, design, governance, and community building. From the outset, the residents have been fully involved at every stage of development, working closely with architects and other facilitators, ensuring that the built environment reflects their values and needs. The design integrates private living units with ample communal spaces and includes areas open to the wider neighborhood, strengthening its role as a social catalyst within the local community. Can70 is about rethinking how people live as they grow older. By participating in the development of their housing, residents provide a community-led alternative to traditional eldercare and housing models. The project aims to create a strong, supportive community and serve as a replicable model for future senior co-housing projects.

Architect(s)

Peris+Toral

Location

Barcelona, Spain

Project (year)

2018-ongoing

Construction (year)

2024-2026

Housing type

Senior co-housing

Urban context

urban context

Construction system

Compressed earth blocks

Status

Unbuilt

Description

Community-led housing projects

The Can70 project exemplifies the significance of community-led housing initiatives, where residents actively participate in the decision making from initiation and planning to development. By engaging in the initial design and subsequent development stages, residents gain a profound sense of ownership. This involvement ensures that the project aligns with the values and aspirations of the dwellers. The community has established a governance structure to facilitate their participation, emphasizing consensus within the general assembly. This structure is composed of five commissions -community, governance, economy, architecture, and external affairs- which play pivotal roles in ensuring effective project management and community engagement. While residents take the lead, they still require resources, public support, and technical assistance to bring the project to fruition. The cooperative Sostre Civic has guided them in navigating legal, economic, and communication aspects with the public sector. This collaborative effort underscores the importance of synergy between community-driven initiatives and external expertise.

Care and mutual support

The community has recognized the importance of incorporating care and mutual support into their co-living model. Their goal is to live in an environment where their members actively support one another, creating a safety net that enhances well-being and quality of life. Through organized activities, informal interactions, and shared responsibilities, care will become an integral part of their daily lives. This way of living together contrasts with the institutionalization of senior care in nursing homes, which the members of Can70 aimed to avoid. Maintaining their autonomy while being part of a supportive community was a key motivation for the group. A significant aid in researching the connection between housing and care was the two-year effort to write the "Guide of Care in the Coliving of Elderly People." This project was supported by a grant from the Department of Elderly People of the City Council of Barcelona. Initially awarded for one year, the grant was extended for a second year. The group systematically explored what care means to them, and the resulting guide is available for everyone to consult, aiding new groups in similar endeavors.

Innovative living forms

The project integrates innovative architectural design and spatial distributions. The building features a spectrum of spaces ranging from private to public, enabling residents to utilize them in diverse ways. The publicly accessible areas of the building connect it with the neighbourhood, communal spaces foster socialization among the building’s inhabitants, and semi-private spaces act as thresholds between public and private realms, giving rise to a smaller nuclei of cohabitation within the building. Since residents plan to live there for the rest of their lives, an important decision was to have single-person units, even for couples. In that way, the person who loses a partner will not have to change their living unit and can continue living in their familiar environment. The group incorporated many apartments using the cluster typology, 4-5 private units of 30m² —each with a bathroom, bedroom, and small kitchenette— around a shared space of 50m², equipped with a kitchen, dining area, and small living room. This layout facilitates easier mutual care within smaller groups. It was also decided to include some conventional 45m² apartments for those who prefer less shared living arrangements. Finally, the building includes various communal spaces, including a shared kitchen, a reading area, and a day centre. An important feature is a semi-open communal space on every floor next to the vertical communication areas, enabling residents to socialise on each floor and seamlessly integrating communal spaces throughout the building.

Relationship to urban environment

The objective of the community has been to create a housing project integrated within the neighbourhood. Since the project is being developed on public land, one requirement of the city council for granting the land to the cooperative was to include public spaces on the ground floor. The group embraced this condition, having already envisioned areas open to the community. The building's ground floor will feature spaces accessible to the public during specific hours, including facilities for physiotherapy, potentially hydrotherapy, a day centre, and care services. Additionally, there will be activities open to the neighbourhood, such as discussions and presentations on well-being and elderly care, as well as storytelling sessions for young children. This approach ensures that the project's social impact extends beyond its residents, fostering social bonds and connections within the local community.

Environmental and social sustainability

From the outset, the group prioritized the project's environmental sustainability, which was evident in the decisions concerning the building's bioclimatic design, construction system, energy efficiency, and shared resources among residents. In collaboration with the architects, Peris+Toral, they chose compressed earth blocks for construction, a material that maintains a stable internal temperature and minimises the need for mechanical cooling or heating systems, thus reducing the environmental footprint of the building. Initially, the group considered using a wooden construction system (CLT), inspired by projects like La Borda in Barcelona. However, rising material cost of wood necessitated a plan change showcasing the group’s flexibility and commitment to find a sustainable solution. Sustainability is also reflected in the project’s various shared resources. The community plans to share daily meals in the communal dining area on the ground floor. Additionally, the clusters of the housing units will include a shared kitchen for four to five residents living together, allowing them to share groceries and take turns cooking. Furthermore, residents will also share laundry facilities. These decisions collectively enhance the project's overall sustainability and foster a strong sense of community.

Societal impact

Can70 will achieve a significant societal impact by envisioning and materializing an alternative model for ageing in the community. The group has created a co-housing project based on autonomy and mutual support among residents, demonstrating the crucial role of community participation in all project phases. This innovative approach highlights the benefits of co-living arrangements for the elderly, where shared responsibilities and collective decision-making contribute to a higher quality of life and increased well-being. In addition to providing a successful model for communal living, the project has also contributed to transform the current legal framework. Can70 has been the first senior project to be incorporated under the grant-of-use scheme, setting a precedent for future initiatives of older communities. This legal recognition paves the way for developing similar projects, allowing the scaling up of senior co-housing.

Alignment with project research areas

The Can70 project intersects with the three research areas outlined in the RE-DWELL program in the domains of design, planning, building, community participation, and policy and financing:

Design, Planning, and Building

Can70 exemplifies sustainable planning by integrating environmental, social, and economic dimensions into its housing design. The project's emphasis on community involvement ensures that sustainability considerations are addressed at various scales, from the building to the neighbourhood level. It incorporates methods and tools to support environmental sustainability in its design, planning, and operation. Choices such as using compressed earth blocks and shared resources enhance the building's sustainability while promoting community engagement.

Community Participation

Can70 represents a community-led housing project with a very high degree of participation from its members. From its initiation to the construction phase, the group has been actively engaged, fostering a robust community, and collaboratively achieving their housing objectives. Can70 embodies collaborative principles by fostering sustainable dwellings through co-creation and resident participation.

Policy and Financing

Can70 explores policy innovations and regulatory instruments to support community-led social housing for older populations, such as the grant-of-use cooperative housing model. The project demonstrates a sustainable approach to housing provision by leveraging public-community partnerships and innovative procurement strategies. Can70 contributes to the discourse on social housing policies by advocating for collective infrastructures managed by the residents. The project's engagement with local governance frameworks highlights the importance of policy interventions and access to public land in promoting sustainable and inclusive housing solutions.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

Can70's alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) reflects its multifaceted impact on social, economic, and environmental aspects, contributing to several of these goals directly and indirectly.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: The project directly contributes to SDG 11 by promoting sustainable urban development through community-led housing initiatives. By integrating environmental considerations, shared resources, facilities and spaces, Can70 fosters a more sustainable and inclusive urban environment. The project's emphasis on community participation and social integration also enhances the resilience and liveability of urban communities, aligning with SDG 11's objectives.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: The initiative’s focus on care and mutual support promotes good health and well-being among its residents. By fostering a supportive environment, it enhances the quality of life of its older population. The project's emphasis on mutual support and access to care services further contributes to SDG 3 by ensuring that older populations and people with disabilities, have access to adequate housing and healthcare facilities.

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities: It addresses inequalities by providing affordable and sustainable housing options for older adults, thereby reducing disparities in access to housing and social support services. Through its community-led approach, it empowers groups to participate in decision-making processes and shape their living environments, promoting social inclusion within the community.

SDG 13: Climate Action: The emphasis on environmental sustainability, such as its bioclimatic design and use of renewable resources, contributes to SDG 13 by mitigating the environmental impact of housing construction and operation. By reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, the project helps combat climate change and promotes climate-resilient communities.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals: The collaborative approach, involving partnerships with the public sector, community organizations, and technical experts, exemplifies SDG 17's call for multi-stakeholder synergies to achieve sustainable development objectives. By leveraging external expertise and resources, the project strengthens its capacity to address complex social, economic, and environmental challenges, fostering sustainable partnerships for achieving common goals.

Related vocabulary

Community-led Housing

Financial Wellbeing

Grant-of-use Cooperative Housing

Public-civic Partnership

Area: Community participation

Created on 05-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-11-2023

Read more ->Blogposts

Sostre Civic: Social Transformation through the Grant-of-use housing model

Posted on 25-11-2024

Secondments

Read more ->

Cooperative housing in Barcelona

Posted on 01-02-2023

Secondments

Read more ->