Diagoon Houses

Created on 11-11-2022

The act of housing

The development of a space-time relationship was a revolution during the Modern Movement. How to incorporate the time variable into architecture became a fundamental matter throughout the twentieth century and became the focus of the Team 10’s research and practice. Following this concern, Herman Hertzberger tried to adapt to the change and growth of architecture by incorporating spatial polyvalency in his projects. During the post-war period, and as response to the fast and homogeneous urbanization developed using mass production technologies, John Habraken published “The three R’s for Housing” (1966) and “Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing” (1961). He supported the idea that a dwelling should be an act as opposed to a product, and that the architect’s role should be to deliver a system through which the users could accommodate their ways of living. This means allowing personal expression in the way of inhabiting the space within the limits created by the building system. To do this, Habraken proposed differentiating between 2 spheres of control: the support which would represent all the communal decisions about housing, and the infill that would represent the individual decisions. The Diagoon Houses, built between 1967 and 1971, follow this warped and weft idea, where the warp establishes the main order of the fabric in such a way that then contrasts with the weft, giving each other meaning and purpose.

A flexible housing approach

Opposed to the standardization of mass-produced housing based on stereotypical patterns of life which cannot accommodate heterogeneous groups to models in which the form follows the function and the possibility of change is not considered, Hertzberger’s initial argument was that the design of a house should not constrain the form that a user inhabits the space, but it should allow for a set of different possibilities throughout time in an optimal way. He believed that what matters in the form is its intrinsic capability and potential as a vehicle of significance, allowing the user to create its own interpretations of the space. On the same line of thought, during their talk “Signs of Occupancy” (1979) in London, Alison and Peter Smithson highlighted the importance of creating spaces that can accommodate a variety of uses, allowing the user to discover and occupy the places that would best suit their different activities, based on patterns of light, seasons and other environmental conditions. They argued that what should stand out from a dwelling should be the style of its inhabitants, as opposed to the style of the architect. User participation has become one of the biggest achievements of social architecture, it is an approach by which many universal norms can be left aside to introduce the diversity of individuals and the aspirations of a plural society.

The Diagoon Houses, also known as the experimental carcase houses, were delivered as incomplete dwellings, an unfinished framework in which the users could define the location of the living room, bedroom, study, play, relaxing, dining etc., and adjust or enlarge the house if the composition of the family changed over time. The aim was to replace the widely spread collective labels of living patterns and allow a personal interpretation of communal life instead. This concept of delivering an unfinished product and allowing the user to complete it as a way to approach affordability has been further developed in research and practice as for example in the Incremental Housing of Alejandro Aravena.

Construction characteristics

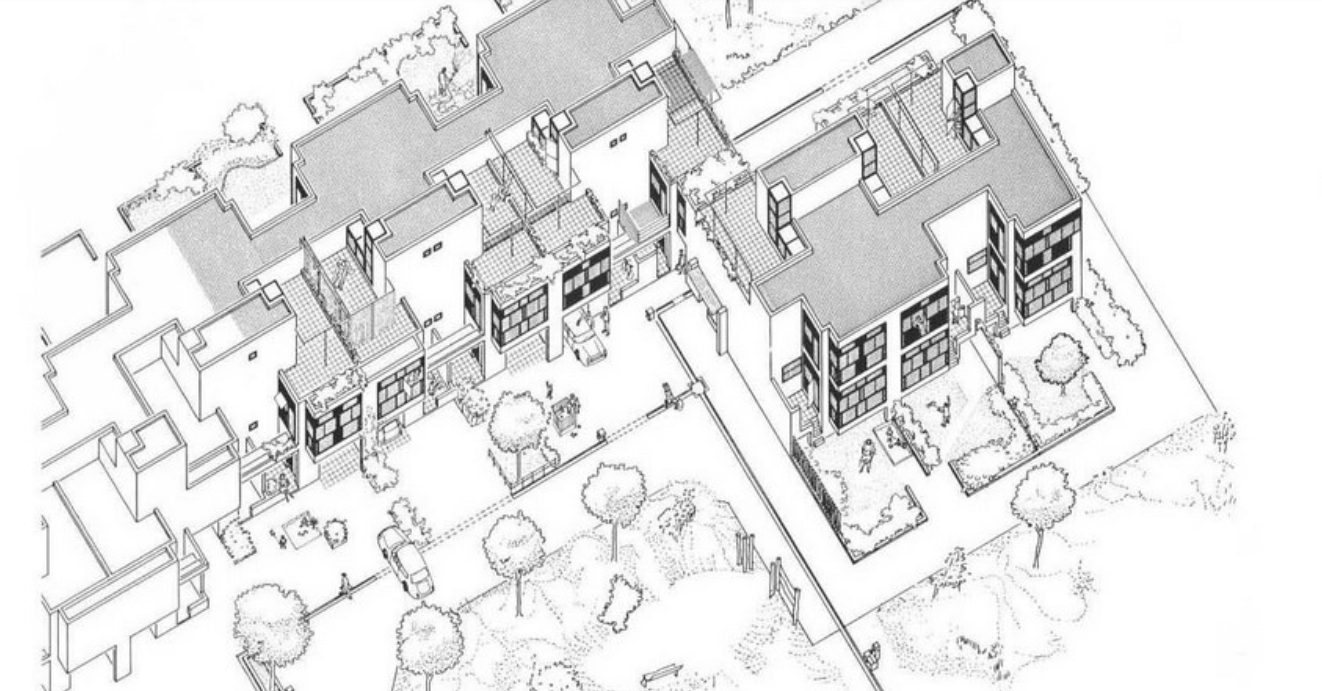

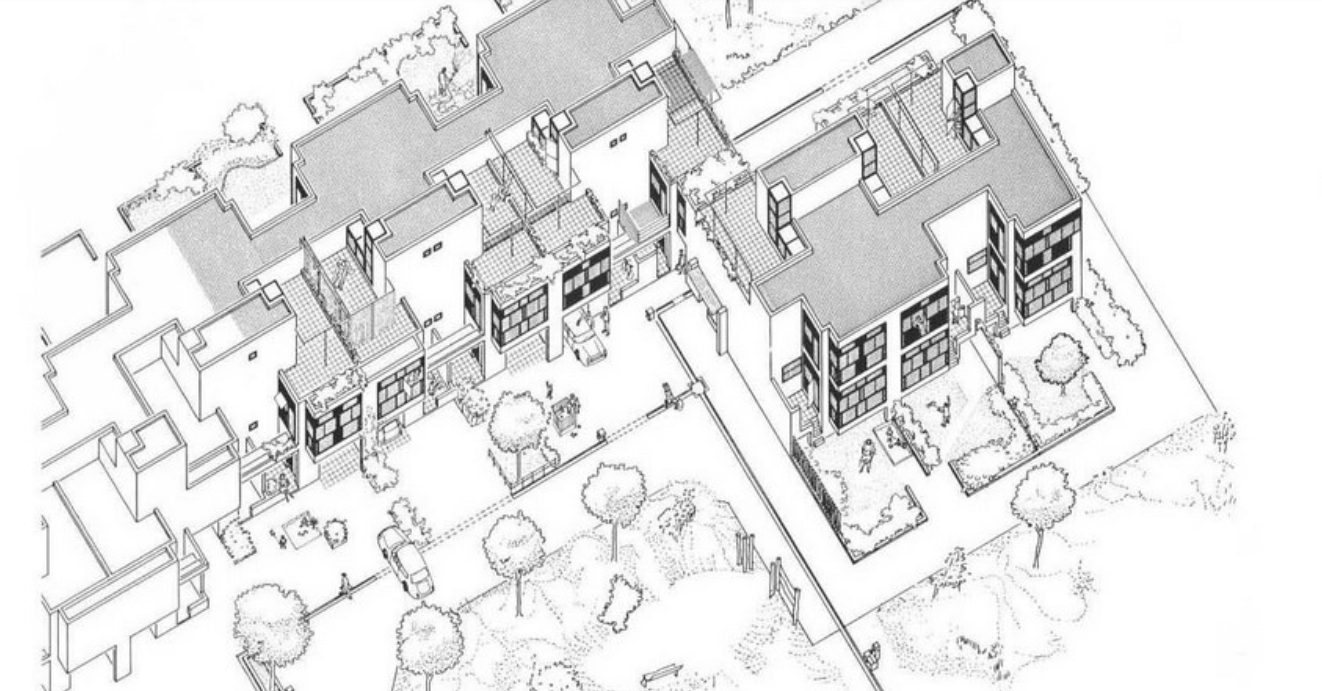

The Diagoon Houses consist of two intertwined volumes with two cores containing the staircase, toilet, kitchen and bathroom. The fact that the floors in each volume are separated only by half a storey creates a spatial articulation between the living units that allows for many optimal solutions. Hertzberger develops the support responding to the collective patterns of life, which are primary necessities to every human being. This enables the living units at each half floor to take on any function, given that the primary needs are covered by the main support. He demonstrates how the internal arrangements can be adapted to the inhabitants’ individual interpretations of the space by providing some potential distributions. Each living unit can incorporate an internal partition, leaving an interior balcony looking into the central living hall that runs the full height of the house, lighting up the space through a rooflight.

The construction system proposed by Herztberger is a combination of in-situ and mass-produced elements, maximising the use of prefabricated concrete blocks for the vertical elements to allow future modifications or additions. The Diagoon facades were designed as a framework that could easily incorporate different prefabricated infill panels that, previously selected to comply with the set regulations, would always result in a consistent façade composition. This allowance for variation at a minimal cost due to the use of prefabricated components and the design of open structures, sets the foundations of the mass customization paradigm.

User participation

While the internal interventions allow the users to covert the house to fit their individual needs, the external elements of the facade and garden could also be adapted, however in this case inhabitants must reach a mutual decision with the rest of the neighbours, reinforcing the dependency of people on one another and creating sense of community. The Diagoon Houses prove that true value of participation lies in the effects it creates in its participants. The same living spaces when seen from different eyes at different situations, resulted in unique arrangements and acquired different significance. User participation creates the emotional involvement of the inhabitant with the environment, the more the inhabitants adapt the space to their needs, the more they will be inclined to lavish care and value the things around them. In this case, the individual identity of each household lied in their unique way of interpreting a specific function, that depended on multiple factors as the place, time or circumstances. While some users felt that the house should be completed and subdivided to separate the living units, others thought that the visual connections between these spaces would reflect better their living patterns and playful arrangement between uses.

After inhabiting the house for several decades, the inhabitants of the Diagoon Houses were interviewed and all of them agreed that the house suggested the exploration of different distributions, experiencing it as “captivating, playful and challenging”1. There was general approval of the characteristic spatial and visual connection between the living units, although some users had placed internal partitions in order to achieve acoustic independence between rooms. One of the families that had been living there for more than 40 years indicated that they had made full use of the adaptability of space; the house had been subject to the changing needs of being a couple with two children, to present when the couple had already retired, and the children had left home. Another of the families that was interviewed had changed the stereotypical room naming based on functions (living room, office, dining room etc.) for floor levels (1-4), this could as well be considered a success from Hertzberger as it’s a way of liberating the space from permanent functions. Finally, there were divergent opinions with regards to the housing finishing, some thought that the house should be fitted-out, while others believed that it looked better if it was not conventionally perfect. This ability to integrate different possibilities has proven that Hertzberger’s experimental houses was a success, enhancing inclusivity and social cohesion. Despite fitting-out the inside of their homes, the exterior appearance has remained unchanged; neighbourly consideration and community identity have been realised in the design. The changes reflecting the individual identity do not disrupt the reading of the collective housing as a whole.

Spatial polivalency in contemporary housing

From a contemporary point of view, in which a housing project must be sustainable from an environmental, social and economic perspective, the strategies used for the Diagoon Houses could address some of the challenges of our time. A recent example of this would be the 85 social housing units in Cornellà by Peris+Toral Arquitectes, which exemplify how by designing polyvalent and non-hierarchical spaces and fixed wet areas, the support system has been able to accommodate different ways of appropriation by the users, embracing social sustainability and allowing future adaptations. As in Diagoon, in this new housing development the use of standardized, reusable, prefabricated elements have contributed to increasing the affordability and sustainability of the dwellings. Additionally, the use of wood as main material in the Cornellà dwellings has proved to have significant benefits for the building’s environmental impact. Nevertheless, while this matrix of equal room sizes, non-existing corridors and a centralised open kitchen has been acknowledged to avoid gender roles, some users have criticised the 13m² room size to be too restrictive for certain furniture distributions.

All in all, both the Diagoon houses and the Cornellà dwellings demonstrate that the meaning of architecture must be subject to how it contributes to improving the changing living conditions of society. Although different in terms of period, construction technologies and housing typology, these two residential buildings show strategies that allow for a reinterpretation of the domestic space, responding to the current needs of society.

C.Martín (ESR14)

Read more

->

Marmalade Lane

Created on 08-06-2022

Background

An aspect that is worth highlighting of Marmalade Lane, the biggest cohousing community in the UK and the first of its kind in Cambridge, is the unusual series of events that led to its realisation. In 2005 the South Cambridgeshire District Council approved the plan for a major urban development in its Northwest urban fringe. The Orchard Park was planned in the area previously known as Arbury Park and envisaged a housing-led mix-use master plan of at least 900 homes, a third of them planned as affordable housing. The 2008 financial crisis had a profound impact on the normal development of the project causing the withdrawal of many developers, with only housing associations and bigger developers continuing afterwards. This delay and unexpected scenario let plots like the K1, where Marmalade Lane was erected, without any foreseeable solution. At this point, the city council opened the possibilities to a more innovative approach and decided to support a Cohousing community to collaboratively produce a brief for a collaborative housing scheme to be tendered by developers.

Involvement of users and other stakeholders

The South Cambridgeshire District Council, in collaboration with the K1 Cohousing group, ventured together to develop a design brief for an innovative housing scheme that had sustainability principles at the forefront of the design. Thus, a tender was launched to select an adequate developer to realise the project. In July 2015, the partnership formed between Town and Trivselhus ‘TOWNHUS’ was chosen to be the developer. The design of the scheme was enabled by Mole Architects, a local architecture firm that, as the verb enable indicates, collaborated with the cohousing group in the accomplishment of the brief. The planning application was submitted in December of the same year after several design workshop meetings whereby decisions regarding interior design, energy performance, common spaces and landscape design were shared and discussed.

The procurement and development process was eased by the local authority’s commitment to the realisation of the project. The scheme benefited from seed funding provided by the council and a grant from the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA). The land value was set on full-market price, but its payment was deferred to be paid out of the sales and with the responsibility of the developer of selling the homes to the K1 Cohousing members. Who, in turn, were legally bounded to purchase and received discounts for early buyers.

As relevant as underscoring the synergies that made Marmalade Lane’s success story possible, it is important to realise that there were defining facts that might be very difficult to replicate in order to bring about analogue housing projects. Two major aspects are securing access to land and receiving enough support from local authorities in the procurement process. In this case, both were a direct consequence of a global economic crisis and the need of developing a plot that was left behind amidst a major urban development plan.

Innovative aspects of the housing design

Spatially speaking, the housing complex is organised following the logic of a succession of communal spaces that connect the more public and exposed face of the project to the more private and secluded intended only for residents and guests. This is accomplished by integrating a proposed lane that knits the front and rear façades of some of the homes to the surrounding urban fabric and, therefore, serves as a bridge between the public neighbourhood life and the domestic everyday life. The cars have been purposely removed from the lane and pushed into the background at the perimeter of the plot, favouring the human scale and the idea of the lane as a place for interaction and encounters between residents. A design decision that depicts the community’s alignment with sustainable practices, a manifesto that is seen in other features of the development process and community involvement in local initiatives.

The lane is complemented by numerous and diverse places to sit, gather and meet; some of them designed and others that have been added spontaneously by the inhabitants offering a more customisable arrangement that enriches the variety of interactions that can take place. The front and rear gardens of the terraced houses contiguous to the lane were reduced in surface and remained open without physical barriers. A straightforward design decision that emphasises the preponderance of the common space vis-a-vis the private, blurring the limits between both and creating a fluid threshold where most of the activities unfold.

The Common House is situated adjacent to the lane and congregates the majority of the in-doors social activities in the scheme, within the building, there are available spaces for residents to run community projects and activities. They can cook in a communal kitchen to share both time and food, or organise cinema night in one of the multi-purpose areas. A double-height lounge and children's playroom incite gathering with the use of an application to organise easily social events amongst the inhabitants. Other practical facilities are available such as a bookable guest bedroom and shared laundry. The architecture of its volume stands out due to its cubic-form shape and different lining material that complements its relevance as the place to convene and marks the transition to the courtyard where complementary outdoor activities are performed. Within the courtyard, children can play without any danger and under direct supervision from adults, but at the same time enjoy the liberty and countless possibilities that such a big and open space grants.

Lastly, the housing typologies were designed to recognise multiple ways of life and needs. Consequently, adaptability and flexibility were fundamental targets for the architects who claim that units were able to house 29 different configurations. They are arranged in 42 units comprehending terraced houses and apartments from one to five bedrooms. Residents also had the chance to choose between a range of interior materials and fittings and one of four brick colours for the facade.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

Sustainability was a prime priority to all the stakeholders involved in the project. Being a core value shared by the cohousing members, energy efficiency was emphasised in the brief and influenced the developer’s selection. The Trivselhus Climate Shield® technology was employed to reduce the project’s embodied and operational carbon emissions. The technique incorporates sourced wood and recyclable materials into a timber-framed design using a closed panel construction method that assures insulation and airtightness to the buildings. Alongside the comparative advantages of reducing operational costs, the technique affords open interior spaces which in turn allow multiple configurations of the internal layout, an aspect that was harnessed by the architectural design. Likewise, it optimises the construction time which was further reduced by using industrialised triple-glazed composite aluminium windows for easy on-site assembly. Furthermore, the mechanical ventilation and heat recovery (MVHR) system and the air source heat pumps are used to ensure energy efficiency, air quality and thermal comfort. Overall, with an annual average heat loss expected of 35kWh/m², the complex performs close to the Passivhaus low-energy building standard of 30kWh/m² (Merrick, 2019).

Integration with the wider community

It is worth analysing the extent to which cohousing communities interact with the neighbours that are not part of the estate. The number of reasons that can provoke unwanted segregation between communities might range from deliberate disinterest, differences between the cohousing group’s ethos and that one of the wider population, and the common facilities making redundant the ones provided by local authorities, just to name a few. According to testimonies of some residents contacted during a visit to the estate, it is of great interest for Marmalade Lane’s community to reach out to the rest of the residents of Orchard Park. Several activities have been carried out to foster integration and the use of public and communal venues managed by the local council. Amongst these initiatives highlights the reactivation of neglected green spaces in the vicinity, through gardening and ‘Do it yourself’ DIY activities to provide places to sit and interact. Nonetheless, some residents manifested that the area’s lack of proper infrastructure to meet and gather has impeded the creation of a strong community. For instance, the community centre run by the council is only open when hired for a specific event and not on a drop-in basis. The lack of a pub or café was also identified as a possible justification for the low integration of the rest of the community.

Marmalade Lane residents have been leading a monthly ‘rubbish ramble’ and social events inviting the rest of the Orchard Park community. In the same vein, some positive impact on the wider community has been evidenced by the residents consulted. One of them mentioned the realisation of a pop-up cinema and a barbecue organised by neighbours of the Orchard Park community in an adjacent park. Perhaps after being inspired by the activities held in Marmalade Lane, according to another resident.

L.Ricaurte (ESR15)

Read more

->

Patch22

Created on 05-12-2023

A response to environmental and economic challenges

The initiators of Patch22, architect Tom Frantzen and building manager Claus Oussoren, aimed at achieving together what they couldn’t manage in previous commissions independently: an oversized wooden structure characterised by flexibility, distinctive architecture, and a strong commitment to sustainability. They established the development company Lemniskade Projects to pursue their goals (Frantzen et al architecten, 2017). Winning the Amsterdam Buiksloterham Sustainability tender in 2009, Patch22 was not only recognised for its exceptional sustainability scores but also for its innovative circular design approach and its capability to adapt to unforeseen future uses. The project's primary objectives were rooted in environmental sustainability, employing renewable and reusable materials, particularly wood for the main structure and facade. Embracing Open Building principles, Patch22 sought maximum flexibility in dwelling sizes and layouts, offering an ingenious response to the environmental and economic challenges outlined in the tender (Kendall, 2021). The 30-meter-tall wooden structure currently hosts 33 dwellings with diverse sizes ranging from 40 m² to 204 m². The building promotes long-term adaptability, as it is prepared to be easily subdivided into six independent office floors or a maximum of 48 apartments (Frantzen, 2023). This showcases how a single support structure can serve multiple generations, accommodating the dynamic needs of its users while addressing some of the current environmental challenges such as material waste, the construction industry’s carbon footprint or the implementation of design for disassembly practices.

A flexible and adaptable building

A flexibility of a building can be enhanced when traditional architectural elements are reassessed. Various strategies were employed to maximize the adaptability of use, layout design, and apartment sizes:

No load-bearing division walls

The timber laminated post and beam structure, in combination with lightweight division walls, became crucial to ensure size variations between apartments and a greater freedom of choice in defining the layouts. Additionally, by superimposing the residential and office regulations, introducing a generous floor height of 4 m, and structurally supporting floor loads of 4 KN, the building accommodates the potential for entirely or partially utilising residential spaces for office purposes (Frantzen et al architecten, 2017).

No vertical shafts inside the apartment

In conventional housing, meter cabinets, kitchens, and bathrooms have typically been constructed near vertical shafts to minimise the length of the drains. When developing Patch22, it was unknown which units would merge to form a single apartment, making it challenging to position the vertical shafts. Two shafts were integrated into the structural core, with pre-installed drains, water and electricity conduits running up to each front door, from where they could be extended to the desired location in an apartment (Council on Open Building, 2023).

Hollow floors to run services horizontally

Patch22 adopts a horizontal services distribution, a common practice in office buildings. The necessary inclination of a toilet drain from the central shaft to the outermost corner of the building results in a floor build-up increase to 50cm. This available space for conduits enables the placement of kitchens and bathrooms anywhere within the dwelling. This departure from the traditional clustering of humid spaces in residential buildings facilitates the creation of multiple floor layouts that respond to the users’ needs.

No meters inside the apartment

By relocating the heavily regulated meters and main switches to the ground floor and placing the non-regulated secondary fuse boxes at each level, Patch22 provides open spaces which can be subdivided in multiple ways (Frantzen, 2023). The independence of the meters from the dwellings streamlines future adaptations with minimal disruptions to the individual living spaces.

Smaller subdivision of legal entities

From a technical perspective, designing a flexible and adaptable building is feasible. But it is also necessary to provide the legal mechanisms that make it possible. In the case of Patch22, each floor contains 8 legal units that can be combined horizontally or vertically (Frantzen, 2023). Although, in its current state, most floors have 3-6 dwellings per flight, these legal units could be divided or merged, sold, or rented independently, used as office or as residential spaces.

Designing for the unknown

Embracing the philosophy advocated by Habraken (OpenBuilding.co, 2023), Patch22 prioritises designing for the unknown. Strategies include over-dimensioning the structure, simultaneous compliance with diverse regulations for different uses, incorporating extra entrance doors, and providing space for additional mailboxes. These approaches keep the design open for future changes, ensuring long-term adaptability.

A sustainable proposal

Patch22 embodies sustainability across multiple dimensions. Environmentally, the building achieves sustainability through a series of strategies: improving energy efficiency, using renewable materials, and fostering layout flexibility. The 2009 design garnered a GPR score of 8.9 and an EPC of 0.2, showcasing its commitment to sustainable practices. The roof, covered with photovoltaic panels, makes the building energy-neutral, while the rainwater collection feeds into a grey water system. The adoption of CO2-neutral pellet stoves, utilising compressed waste wood as fuel, further underlines Patch22’s commitment to eco-friendly energy sources (Frantzen et al architecten, 2017). Despite the challenges posed by fire and acoustic regulations, the building boldly features wood as its main material, with additional thickness added to columns and beams to comply with safety standards. This decision, although increasing costs, remains more economical than the alternative solution of building with 2D CLT panels (Frantzen, 2023). Additionally, the emphasis on long-term layout flexibility aligns with environmental sustainability by reducing waste during future adaptations and facilitating component disassembly. From a social standpoint, involving residents in the design process fostered diversity and strengthened the sense of belonging. Finally, the economic sustainability of Patch22 is evident in its adaptable support, serving as a long-term investment that evolves with changing needs, potentially acquiring different uses over time, benefitting both the planet and the economic interests of its users.

Construction characteristics

The support components, encompassing the structure, façade, and core of Patch22, are highly prefabricated, facilitating a swift and precise assembly process on-site while minimising waste and reducing disruptions. The structure incorporates over-dimensioned laminated wooden beams and columns, along with vertical core constructed with prefabricated concrete panels (Open Building NOW!, 2020). The NW and SE façades employ CLT panels with a thickness of 220mm, while the NE and SW orientations, serving as the main facades, create loggias on both sides. The loggia's interior façade features modulated sliding doors with CLT prefabricated frames, allowing for the free placement of interior partitions by strategically positioning mullions every 3 meters (Frantzen, 2023). Externally, the loggia is characterised by redwood truss beams with bolted connections to steel joints which facilitate their future disassembly. These buffer zones can be fully enclosed with glazed modular panels in winter or left open with a fixed handrail during the summer.

The floor plays a pivotal role in leveraging the flexibility of the apartments within the structure. Employing a Slimline structural flooring system made of IPE 400 steel profiles and a 70mm reinforced concrete slab below, this design allows services to run efficiently within the hollow floor, reaching even the most remote corners of each apartment. After installing drains and other facilities, the floor is topped with an acoustic membrane, a Lewis profile sheet, and 8cm of anhydrite screed with underfloor heating. While initially considering demountable top floor tiles, this solution was deemed complex and expensive compared to the anhydrite screed, which proved more cost-effective and flexible (Frantzen, 2023). By planning in advance for the placement of maintenance registration points to the floor cavity, it was possible to enable access for the necessary alterations while maintaining practicality and affordability.

User customisation process

The customisation process at Patch22 began with a search for prospective residents through social media, leveraging it as a platform to connect with individuals interested in actively designing their living spaces in collaboration. Once on board, residents were presented with the opportunity to shape their homes within an entirely empty interior. A catalogue of multiple variations was offered by the architects, allowing some residents to select a pre-designed option that suited their preferences. Alternatively, others opted for a more collaborative approach, working closely with Frantzen architects to create a custom layout. Some residents took an independent venue, either designing their dwellings themselves or hiring another architect to develop their interiors (Frantzen, 2023). Throughout the process, Frantzen provided comprehensive guidance on the technical requirements, ensuring compliance with fire and soundproofing regulations. Residents could choose to have the base installations in the floor installed by the main contractor or to receive the bare shell and install them themselves. This inclusive approach allowed residents to actively contribute to the unique character of Patch22 while ensuring the resiliency of the building support for future generations.

C.Martín (ESR14)

Read more

->