Limited uptake of renovation subsidy schemes among low-income homeowners

Created on 17-10-2023

Although building retrofitting seems to promise long-term cost savings and could greatly improve the lives of low-income homeowners, in reality, these individuals face notable obstacles that prevent them from accessing government subsidy schemes. These obstacles primarily stem from economic, institutional, behavioural, and informational factors. Economically, the high upfront costs are often cited as a major discouragement from pursuing retrofitting. Institutionally, complex bureaucratic procedures and a lack of streamlined processes for accessing subsidies can pose significant barriers. Behaviourally, actors such as the disruption caused by a renovation project and resistance to change can also play a substantial role. Lastly, inadequate or insufficient information regarding the availability and benefits of subsidy schemes acts as a major hurdle. These barriers are often applicable to higher-income homeowners as well, but previous research suggests that they particularly affect low-income homeowners. This underscores the need for a more targeted approach in providing renovation subsidies for residential dwellings.

Systems knowledge

Actors

National government

This actor represents the central governing body and authority responsible for overseeing and managing the affairs of a nation, including policymaking, legislation, and implementation within a certain geographic area.

Public banks

Financial institutions that extend loans and credit to various entities such as social housing providers and governments to support their initiatives, projects, or operations in the public interest.

Method

Comparative policy analysis

Refers to evaluating and examining the outcomes of policies, regulations, or approaches across different contexts 'ex ante' or 'ex post' to inform decision-making.

Stakeholder consultation

This entails actively engaging and gathering input from individuals or groups who are directly affected by policies, aiming to incorporate their perspectives and insights into the decision-making process.

Tools

Randomised controlled trial (RCT)

This involves the random assignment of participants into experimental and control groups to assess the effectiveness or impact of a particular intervention or policy, such as a renovation subsidy scheme, through comparison and analysis.

Focus group

A qualitative technique involving a selected group of individuals assembled to provide insights, opinions, and feedback on specific topics, products, or policies, facilitating in-depth understanding and informed decision-making.

Target knowledge

Topic

Building retrofitting

Building retrofitting involves the renovation and improvement of existing structures to enhance energy efficiency, comfort, and sustainability.

Dimension

Environmental

This dimension focuses on understanding and addressing the environmental challenges and concerns related to human activities and their impact on the natural world.

Social

This dimension relates to aspects influencing or impacting people, communities, and societal structures.

Governance

This involves networks, systems and processes that steer decision-making, service delivery and policy implementation.

Level

Country

The political structure governs a specific geographical area and accommodates a specific population group.

Municipal

This level refers to the local administrative or governmental unit, typically a city or town, responsible for local governance, services, and decision-making within a defined geographic area.

Transformation Knowledge

No references

Related cases

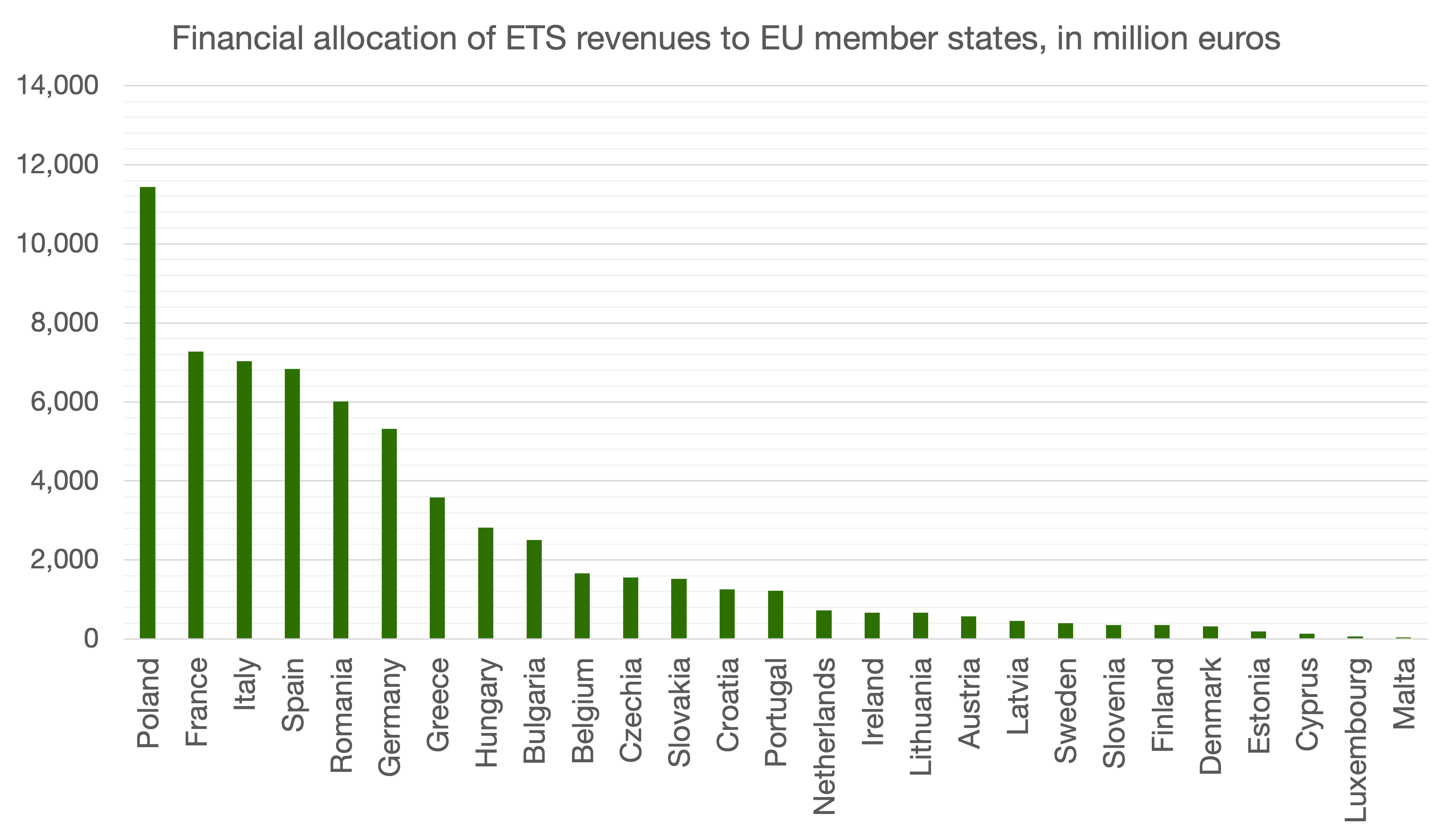

The Social Climate Fund: Materialising Just Transition Principles?

Created on 11-07-2023

Related vocabulary

Just Transition

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->