Die Baupiloten Berlin

Created on 29-07-2024

Overview

The impetus behind the creation of Baupiloten was the growing concern within German architectural associations about the education offered at architecture faculties. At the turn of this century, architectural education in Germany was severely criticised on the basis of its perceived distance from the “practical necessities of the profession”, with students training only in abstract projects that would never be built (Hofmann, 2004, p. 115). The founder and leader, Susanne Hofmann, has been involved both in practice and academia/research and is a firm believer that intertwining these two pillars offers much broader opportunities for students to learn through direct exposure in reality-based conditions, thus bridging the gap between architectural education and professional practice.

In the spirit of restructuring prevalent architectural curricula, the Studienreformprojekt at TU Berlin set forth the following goals, which Baupiloten set to accomplish (Hofmann, 2004, p. 117):

Develop a connection between practice and research-oriented learning through building projects

Provide opportunities to explore the interdependences between the design and building process

Enhance interdisciplinary connections between the different fields of expertise that can be found in TU Berlin

Foster the project motivation and responsibility of students by allowing them to be a part of every stage, from the conception to the construction stages

Encourage students to test their ideas in a real, tangible project

Participation and atmosphere

Participation of non-experts

One of the core tenets of Baupiloten is the recognition of user knowledge as equally important to that of the “experts”. Users possess a specific kind of experiential, contextualised expertise on spatial arrangement, which, as Hofmann posits, becomes an invaluable source of information that can only be tapped into through real, active inclusion in the design process (Hofmann, 2019). Therefore, participation becomes a central focus in the Baupiloten approach, creating impactful and meaningful designs whose components can be traced back to the actual needs and desires of the people they design for.

While participation has often been criticised on the basis of responsibility and accountability diffusion, superficiality and risks of manipulation and tokenistic practices (Miessen, 2010), Hofmann argues that participation can (1) amplify creativity and invention, both through the multiple perspectives entering the discussion and through the need for creative solutions to facilitate the dialogue (e.g. discussion game design). It can (2) reduce costs and shorten the timeframe, as visions for the desired interventions are jointly shaped, so that time and cost estimations can be measured and planned with fewer amendments during the process. It can (3) promote social cohesion, through the co-existence and interaction of diverse groups. Finally, it can (4) ensure architectural quality of the finished product by securing a clear correspondence between the final design and the user needs (Hofmann, 2018).

While the clear-cut binary of “expert” and “layperson” slowly dissolves, flexibility becomes even more crucial when it comes to the role of the architect; facilitating and moderating skills arise as equally crucial during the process, and effective communication becomes the key to a successful process. This does not mean that space design and production should no longer be the core competence of an architect, but rather that it needs to be expanded and renegotiated to fit the needs of a diverse project team (Hofmann, 2019).

Therefore, one of the focal questions that Baupiloten seeks to answer is how “can communication between citizens, architects, authorities, business, social movements – everyone – be facilitated without a loss of quality?” (Hofmann, 2018, p. 117)

Perception of atmospheres as a means of communication

Within Baupiloten, “atmosphere" is understood as the subjective perception of a space's emotional and sensory qualities, which significantly influences user experience. This concept extends beyond mere aesthetics, encompassing the interplay of light, sound, texture, and spatial arrangements to create a cohesive emotional impact. Baupiloten utilises this understanding of atmosphere to facilitate the communication of design intentions and foster a collaborative co-design process. By articulating the desired atmospheric qualities, designers can convey complex ideas and emotions that are otherwise challenging to express through conventional architectural drawings or technical specifications.

Atmosphere articulation becomes a central tool in the co-design process, engaging users and stakeholders in the creation of a shared vision for the space. Through workshops, mock-ups, and immersive simulations, participants experience and respond to the proposed atmospheres, providing valuable feedback that informs the design development. This collaborative approach ensures that the final design resonates with users' needs and preferences, creating spaces that are not only functional but also emotionally engaging. By focusing on atmospheres, Baupiloten bridges the gap between technical design and human experience, fostering a more inclusive and participatory design process that enhances the overall quality and impact of the built environment (Hofmann, 2019).

Methodology and learning objectives

Methodology

Baupiloten follows a 4-stage methodology aimed at kickstarting the dialogue and subsequent collaborative design process among participating stakeholders (Hofmann, 2018):

Team-building: raising awareness and building a common ground for communication through dialogue and other interactive activities.

Users’ everyday life: observing and recording daily activities.

“Wunschforschung”: researching the needs and desires of the users in a systematic manner.

Feedback: optimising the design according to comments received by the participants.

This methodology includes three broad, equally important categories of participating stakeholders:

Users: the “citizen experts”, bringing the knowledge of the everyday life to the table

Clients: the individuals or entities who commission the project and define the financial constraints that the design and construction must adhere to.

Architects: professionals and experts whose role is to facilitate and moderate the interactions, optimising their level of involvement to meet the process’s requirements.

Projects begin with students developing parallel designs. After a few weeks, the ideas are scrutinised to identify which concepts should be further refined, and students proceed to create and discuss various versions, ultimately selecting the final concept. Once a project is deemed convincing, it is divided into distinct packages for each student to develop independently. These design packages are intended to be sufficiently challenging yet comprehensible enough for the students to carry out successfully.

Overall, projects are divided by planning stages, potentially spanning through multiple semesters, and their schedule is aligned with the academic year to ensure professional management and relevance to real-world contexts. Instead of presenting related topics and themes as abstracted theory within the project (e.g. building regulations, lighting design principles, structural engineering, etc.), students are encouraged to learn experientially, through on-demand contextualising knowledge from related fields and topics as they progress on the project at hand (Hofmann, 2004).

Learning objectives

The learning objectives are separated into two main categories, as follows (Hofmann, 2004):

Fostering professional competences related to the different stages of a project

Developing design skills

Training in designing from concept to construction detail

Learning about cost-calculation and budgeting

Developing self-reflexive and assessment skills and methods

Enhancing interpersonal, communication and teamwork-related skills

Cultivating management skills

Learning how to interact with the various stakeholders involved in a project (clients, public authorities, craftsmen, manufacturers and building contractors)

Learning how to prepare and give effective presentations

Training in performing at and leading client meetings

Notable projects

Erika Mann Elementary School (or “the snuffle of the silver dragon”)

The Erika Mann Elementary School in the Wedding area of Berlin. When the phase 1 of the project was initiated (2003), Wedding had a high unemployment rate and a significant migrant population from non-German-speaking backgrounds. Baupiloten was tasked with initiating a collaborative design process, aiming to enhance the school premises with additional learning and living environments. The aim was to improve the quality of life within the school and make it an important hub for the whole neighbourhood.

Operating under the principle of “Form follows kids’ fiction”, the school students engaged with Baupiloten students and tutors in a series of design workshops spanning two phases: the first taking place in 2003 and the second in 2008, following the extension of the school’s operating hours to all-day. These workshops resulted in a proposal featuring a series of interventions designed to contrast the rigidness of the school’s hallways by creating “fantastical and poetic worlds, culminating in the fictive "Snuffle of the Silver Dragon"”(ArchDaily, 2009).

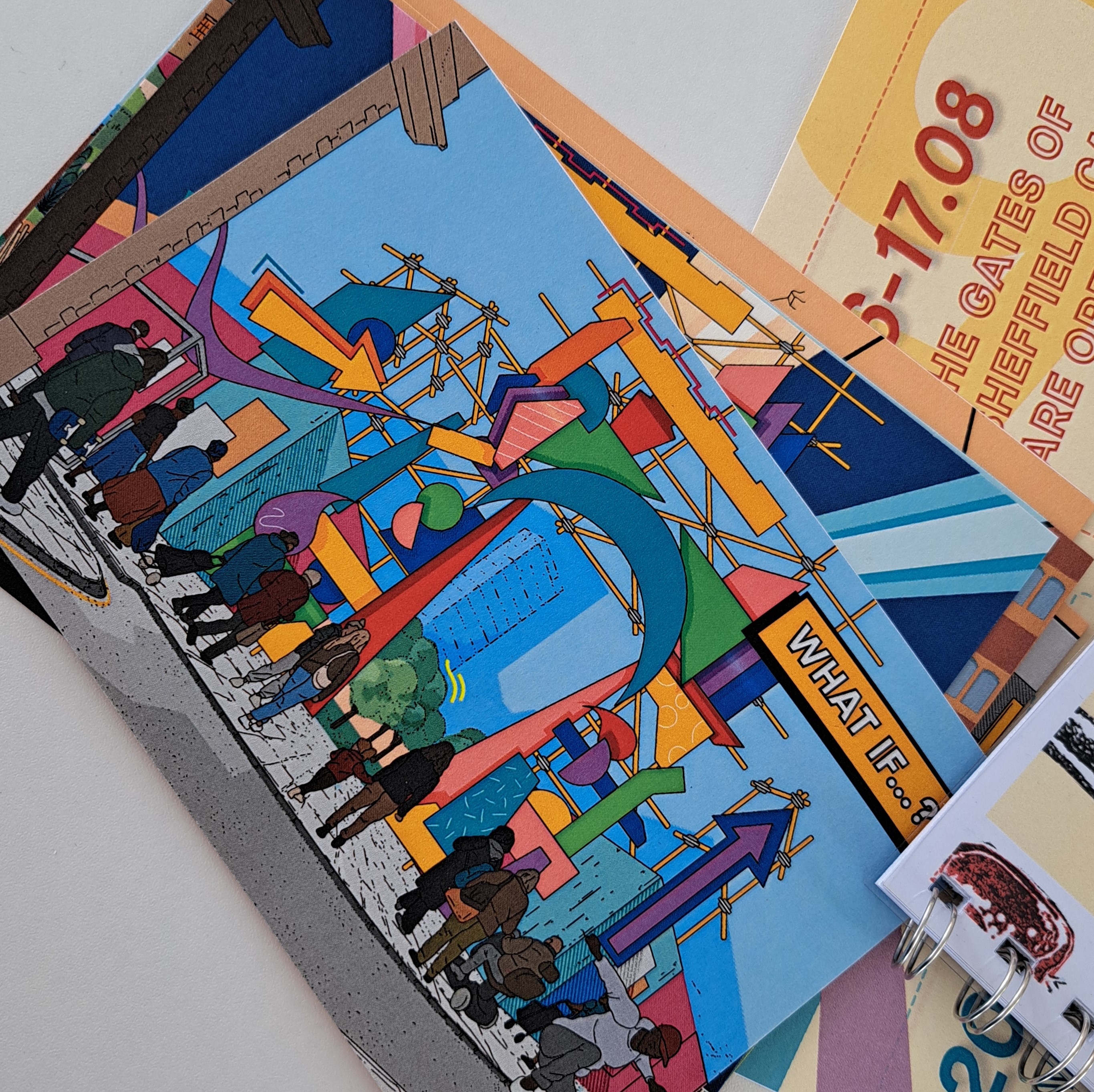

Kotti 3000

Kotti 3000 (alternatively, Neighbourhood 3000), is an interview tool and game specifically designed to encourage participation from people, such as migrants, whose voices, opinions and desires are often overlooked.

In this game, the players begin with a map of the neighbourhood. Through discussion and interaction, they can place a wide range of pictogram stickers on it. Each pictogram represents a type of urban equipment or function and “costs” a varying amount of points (e.g. cinema=300 points, vegetable garden=100 points). The overarching goal is to collaboratively “spend” the 3,000 points available to the participants on different types of interventions based on their needs and desires (Baupiloten, n.d.; Khafif, 2024).

E.Roussou (ESR9)

Read more

->