Porto 15, a public experiment to foster collaborative housing

Created on 13-12-2023 | Updated on 26-01-2024

Porto 15 is the first Italian public rental co-housing project dedicated to people under 35. Produced by three public bodies of Bologna from the welfare sector, it was designed and subsequently managed in collaboration with the residents. Through the renovation of a vacant council-owned building in the centre of Bologna, the project attracted public attention to limiting land consumption and improving the management of public properties. In 2017, residents were able to move in, after an intense co-production period involving the residents and the public administration.

This project is the first example of public engagement to set the scene for an alternative form of housing, different to the archetype of public housing. Porto 15 sets a milestone in changing the paradigm of the public housing resident. Through this project, the public administration redefines the position of the administration as a service provider, and of the tenant as a service user. In this context, the new public housing beneficiary is expected to be an active participant, fostering both an internal community within the co-housing and an external community through social and environmental sustainability actions in the neighborhood. The collaborative design and management of the shared spaces of the building should thus build new community competences.

Following the example set by this project, Bologna adopted its first building regulations for collaborative housing. In this regard, Porto 15 is expected to play a pivotal role in inspiring other affordable co-housing endeavours not only in the city but throughout Italy.

Instrument

regulation, community engagement

Issued (year)

-

Application period (years)

-

Scope

country, regional, local

Target group

young, low income group, vulnerable group

Housing tenure

tenancy, public housing, co-housing

Discipline

sociology, public policy, urbanism

Object of study

Outcomes Instrument

Description

Context

In contemporary Italy, public housing provision follows two main typologies: edilizia residenziale pubblica (ERP) or "public residential housing", with rents determined by law based on residents’ incomes, and edilizia residenziale sociale - (ERS) or "social residential building" offering affordable rents for individuals who do not meet public housing criteria and cannot access housing in the private market (Storto, 2018; Divari, 2019). The ERS rent is capped, and tenants are selected through a public call. Under this typology, there is a specific fund for ERS housing which also serves social networking purposes. Porto 15 belongs to this stream of projects.

Project

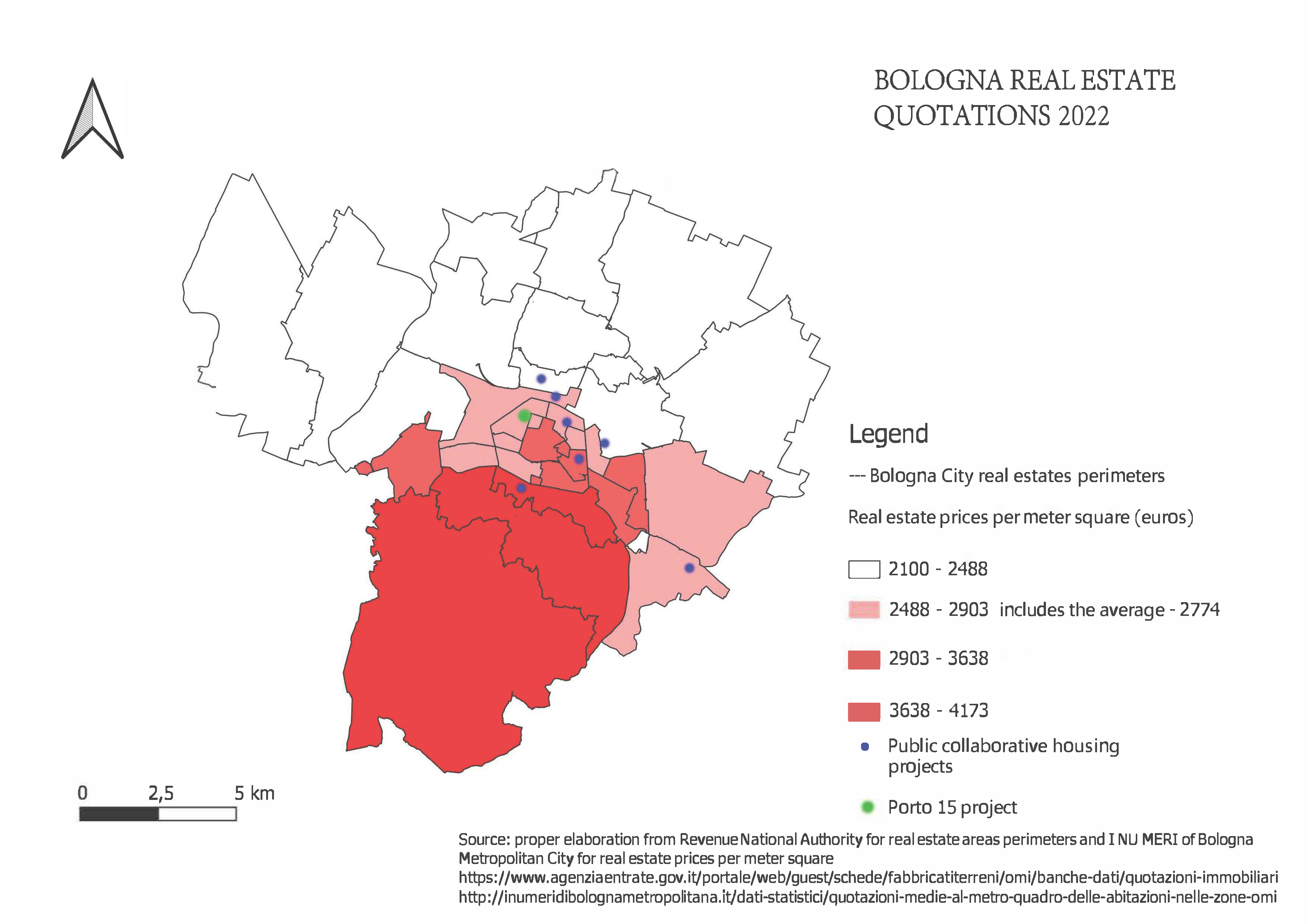

Porto 15 is an ERS development financed through a national call for housing projects from 2015 that aimed to promote housing autonomy for people under 35 by expanding and diversifying the affordable housing provision. The municipality of Bologna was one of the winners of the call. It initiated the housing project in collaboration with two other public bodies: the municipal welfare service provider and the regional public housing manager. The public institutions’ aim was to address housing demand and promote collaborative living as a desirable housing model among young people.

Collaborative housing in Italy is mainly based on private property, long-term investment and selective communities (Rogel, 2018). This category of housing can encompass cohousing, residents’ cooperatives, solidarity condominium and eco-villages, among other. Porto 15 represents a pioneering experiment in collaborative housing, expanding access to it through a public rental scheme. This scheme responds to the co-housing category, by keeping private space to a minimum and complementing it with shared living spaces. In this case, the ‘co’ not only signifies mutual help relationships among tenants but also reflects collective efforts in networking to promote a collaborative housing culture in the neighbourhood (Calastri, 2013).

In the Porto 15 experiment, future residents received 40 hours of training aimed at fostering group cohesion. The selection process entailed studying candidates’ motivations and profiles to create a socially mixed diverse community, including individuals with specific fragilities such as migration background, disability, and integration difficulties. Residents’ origins are diverse, including Syria, Peru, Russia, Spain, Morocco and various regions of Italy. The intention was to extend beyond a self-contained community, selecting individuals based on their motivation to build social ties beyond their homes. Currently, the co-housing accommodates 25 adults and 12 children. Prospective residents were encouraged to establish an association, disseminate the positive implications of the collaborative housing model, and facilitate sense-making processes regarding the values and principles that underpin this type of housing.

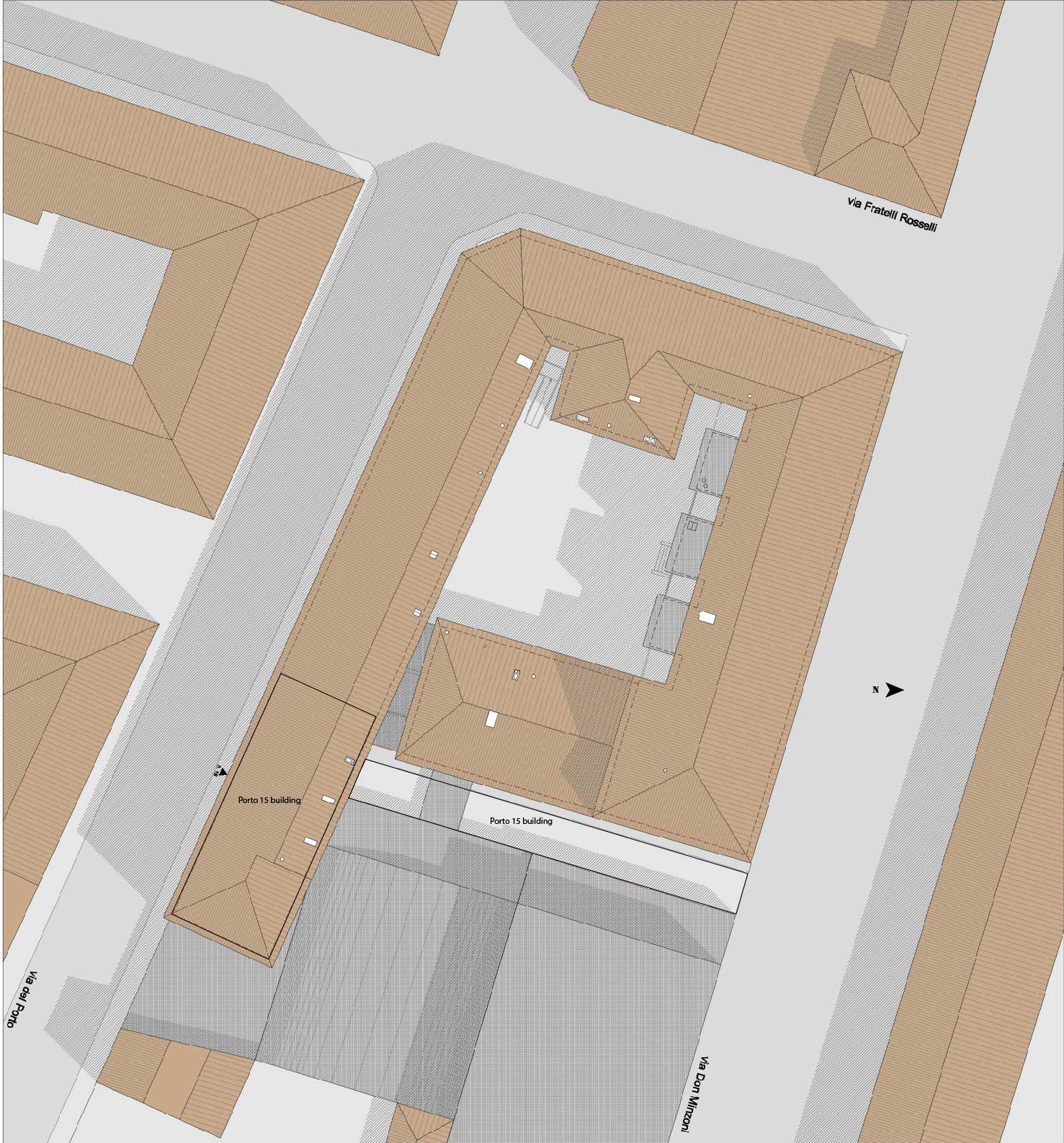

The housing development occupies a portion of a historic building dating back to 1914 which underwent a renovation to be repurposed as a co-housing facility. It comprises eighteen units, consisting of 9 two-bedroom and 9 three-bedroom apartments, along with a shared apartment and a multipurpose room. The premises also include a courtyard and communal spaces in the basements. Rent is set at a standard rate of seven euros per square meter, approximately 300 euros per month, depending on the apartment size. This stands in stark contrast to the average of eighteen euros per square meter in the private housing market within the central districts of Bologna, a city facing significant housing pressure.

Co-housing and tenant – landlord relations: changing postures?

In Italy, recipients of public housing have traditionally been viewed as beneficiaries of either monetary subsidies for rent and bills or public house for living. The prevailing approach by public management perceived these individuals as users with uniform needs, leading to the delivery of standardised services to satisfy them. (Andersen & Pors, 2016). However, a “governance metatrend” (Mortensen et al., 2020) is emerging, fostering a hybridization of roles for service providers and users, encouraging co-production, capacity-building, and a mutual learning perspective. With Porto 15, the public administration seeks to transform itself into an enabler and a place-maker, striving to create a space for opportunities, not just in physical terms but also socially. This marks a shift in attitude towards public housing residents, who are now actively engaged in creating and collaborating, rather than passively receiving social benefits. In Porto 15, public bodies are shaping a new social dynamic by adopting a strength-based approach to social welfare (Price et al., 2020).

In the final phase of the building renovation, as the group of dwellers was being formed, future residents participated in the co-design of the basements together with the architects. They collectively decided to incorporate a bicycle repair workshop, a shared laundry, communal storage and a music practice room in that space.

After the group came together, irregular contact with the public service provider resulted in an interaction based on questions/answers or problem/solution, resembling a landlord-tenant relationship rather than the intended horizontal collaboration. Paradoxically, this gap created an open space for innovation, allowing the co-housing group to take a proactive role. The group established a self-managed network, which was acknowledged by public authorities.

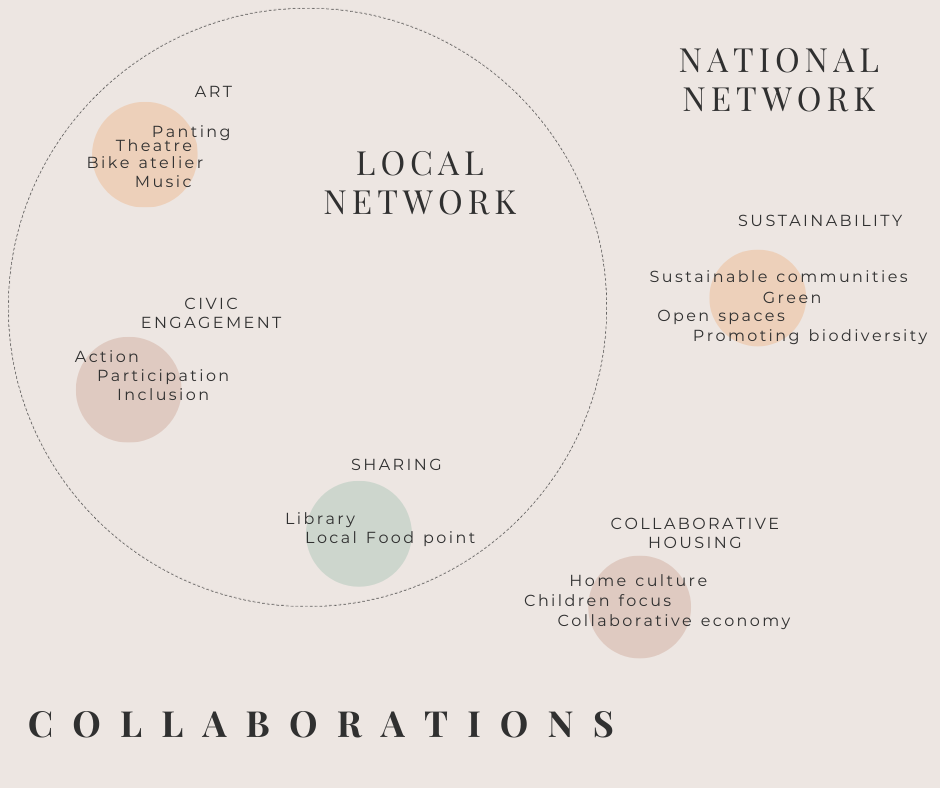

In its inaugural year, the Porto 15 community engaged with twenty-seven different associations, took part in twenty-one projects (leading one), and organized various public events. All of these initiatives received endorsement from both the municipal welfare service provider and the municipality, serving as showcases for the collaborative housing model. Notably, the association joined the “European Collaborative Housing Day” in 2022, also hosting activities from local groups in the shared spaces.

Co-housing in the local urban regulation: a transformative impact?

Porto 15 played a pivotal role in shaping the first normative definition of co-housing in Bologna, setting an example for the entire country. While collaborative housing was vaguely mentioned in a 2014 regional law as an “integrated solution for local communities to meet their goals”, the Bologna building code introduced more precise principles for “collaborative and solidarity-based housing”. These principles explicitly aim to prevent speculation and promote environmental sustainability, fostering homogenisation among emerging projects falling under the co-housing label. Households involved in such projects are required to adhere to building and environmental sustainability principles. Additionally, they must actively participate in community actions, engage in the design and management of common spaces, share practices within the neighbourhood, and organize public events.

Co-housing offspring in Bologna: a generative effect?

The Housing Plan of Bologna incorporates a dedicated section for the development of new “collaborative and solidarity-based” public projects in the city, drawing inspiration from the pilot project of Porto 15. The emergence of second generation co-housing projects started with the Salus Space in 2019, a “collaborative village” funded by the European Union and characterized by a diverse governance model endorsed by the municipality.

This new wave of projects aims to forge connections between collaborative housing and various policies, shaping a fresh narrative around collaborative housing. These policies prioritize environmental sustainability, with an upcoming co-housing project focusing on creating the first community energy collective for nearly zero-energy self-consumption in a public building. The second area of intervention emphasizes community building with an intergenerational and intersectional dimension, along with the development of a collaborative condominium. The third planned intervention involves awareness initiatives within co-housing for young people and families, promoting efforts against organized crime.

The overarching goal is to create a lasting inventory of affordable social housing, serving as a social catalyst for the territory. The residents of Porto 15 plan to contribute to this vision by sharing their expertise with future residents of other collaborative projects. This will involve organizing conferences, extending invitations to shared activities, and participating in events organized by future co-housing groups.

Public housing production in Italy faces the challenge of establishing secure financial channels. To achieve this goal, municipalities must devise solutions utilizing a range of financial resources, spanning from European to municipal levels, to ensure the successful development of collaborative housing projects. Looking forward, key strategies will entail incentivizing private investors to invest in social housing development and fostering a reflection on the role of social cooperation in affordable housing provision.

Alignment with project research areas

Design, Planning, and Building

The project encompassed the renovation of a portion of a historical building, addressing the need to reuse and revitalize the extensive, unused public estate stock. The project aims to enhance the energetic efficiency of an early twentieth century building by implementing sustainability upgrades. The interventions constituted a complete retrofit, including thermal insulation and the replacement of systems (heating, ventilation, electricity, water). Future residents participated in the design of the basements, choosing to create a shared space instead of private garages as proposed by the architect.

Community Participation

As a rental co-housing scheme, Porto 15 relies on the participation of residents to cultivate social networks within and around the housing community. Their involvement started with the co-design of the project, encouraging the future community to take ownership of the space and promote a sense of belonging. Furthermore, various communal spaces were deliberately left vacant, empowering residents to decide on their collective use, establish relationships, participate in management, initiate entertainment initiatives, collaborate on projects, and host people and events. To formalize their collective efforts, the group established an association that promotes collaborative initiatives for the neighbourhood and the city.

Policy and Financing

Porto 15 has opened up broader perspectives on existing norms, providing an opportunity for local authorities to establish new regulations that encourage future collaborative housing projects, with clear technical criteria and a strong emphasis on social utility. The initiative has sparked a reflection on financing alternatives and continuity, prompting the establishment of specific funding for affordable housing at the municipal level, including a specific fund for co-housing. In addition, European funding, particularly through initiatives like the national Recovery and Resilience Plan, is expected to play a pivotal role in supporting affordable social housing in Italy in the following years.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

1. NO POVERTY. Porto 15 is part of a broader set of policies addressing the provision of affordable and social housing by the municipality of Bologna. It is specifically tailored for young people whose financial conditions place them below a certain threshold: individuals who are not in extreme poverty but lack sufficient means to enter the private housing market.

3. GOOD HEALTH AND WELL BEING. The project advocates a holistic vision of well-being, fostering social and relational opportunities for both for adults and children. It addresses physical and mental well-being through open initiatives promoting health practices and provides technical support for bike repair to promote slow mobility in the city centre.

9. INDUSTRY, INNOVATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE. The renovation project aims to reconcile the preservation of an existing historical structure with the requirements arising from the unconventional residential use of a cohousing project. Involving public subjects, architects, and residents in the design phase ensures more inclusive and effective housing solutions.

11. SUSTAINABLE CITIES AND COMMUNITIES. Porto 15 connects with a wide community in the metropolitan area of Bologna, fostering knowledge and networks within civil society. It serves as a social pillar within a network node for collaborative housing, sustainability, and the promotion of inclusivity, valuing differences and countering discrimination.

12. RESPONSIBLE CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION. The Porto 15 community fosters the consumption of local products and has evolved into a distribution hub for local food through a co-operative purchasing group. It creates links between sustainability practices by hosting numerous events and conferences on the theme, and has its own open repair shop.

17. PARTNERSHIPS FOR THE GOALS. The partnership forged for this project brought together public agencies and the municipality with the shared goal of promoting the co-housing model as an innovative form of public involvement in the provision of housing and social services, aligning with SDGs. This pilot project shows the commitment of public entities to collaborate and diversify public housing provisions, and develop more inclusive scenarios.

References

Andersen, N. Å., & Pors, J. G. (2016). Public Management in Transition: The Orchestration of Potentiality (1st edition). Policy Press.

Calastri, S. (2013). Nuove soluzioni per l’abitare condiviso e intergenerazionale. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282133362

Divari, A. (2019). De social housing#an italian brief history. Nomos 1/2019.

Mortensen, N. M., Brix, J., & Krogstrup, H. K. (2020). Reshaping the Hybrid Role of Public Servants: Identifying the Opportunity Space for Co-production and the Enabling Skills Required by Professional Co-producers. In H. Sullivan, H. Dickinson, & H. Henderson (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of the Public Servant (pp. 1–17). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03008-7_17-1

Price, A., Ahuja, L., Bramwell, C., Briscoe, S., Shaw, L., Nunns, M., O’Rourke, G., Baron, S., & Anderson, R. (2020). Research evidence on different strengths-based approaches within adult social work: A systematic review. NIHR. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr-tr-130867

Rogel, L. (2018). Cohousing: L’arte di vivere insime : principi, esperienze e numeri dell’abitare collaborativo : la mappatura in Italia. Altra economia.

Storto, G. (2018). La casa abbandonata: Il racconto delle politiche abitative dal piano decennale ai programmi per le periferie. Officina edizioni.

Related vocabulary

Collaborative Housing

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 11-06-2024

Read more ->Blogposts

Exploring Urban Innovation in Lisbon

Posted on 20-11-2024

Secondments

Read more ->